The Myth of Gerald Ford's Fatal 'Soviet Domination' Gaffe

A boneheaded moment during a 1976 debate didn’t doom the president’s reelection, and most other such mistakes don’t affect outcomes either.

Over the weekend, Donald Trump offered some unusual remarks about Ukraine during an interview with George Stephanopoulos. Speaking about Russian President Vladimir Putin, the Republican presidential nominee said, “He's not going to go into Ukraine, all right? You can mark it down and you can put it down, you can take it anywhere you want.”

Of course, Putin has already seized Crimea, which is a piece of Ukraine. When Stephanopoulos pointed this out, Trump argued that was for the better: “You know, the people of Crimea, from what I've heard, would rather be with Russia than where they were.” On Monday, Trump said he was simply arguing that Putin would not take anymore, and he also made the case for simply ceding Crimea to Russia, to avoid World War III.

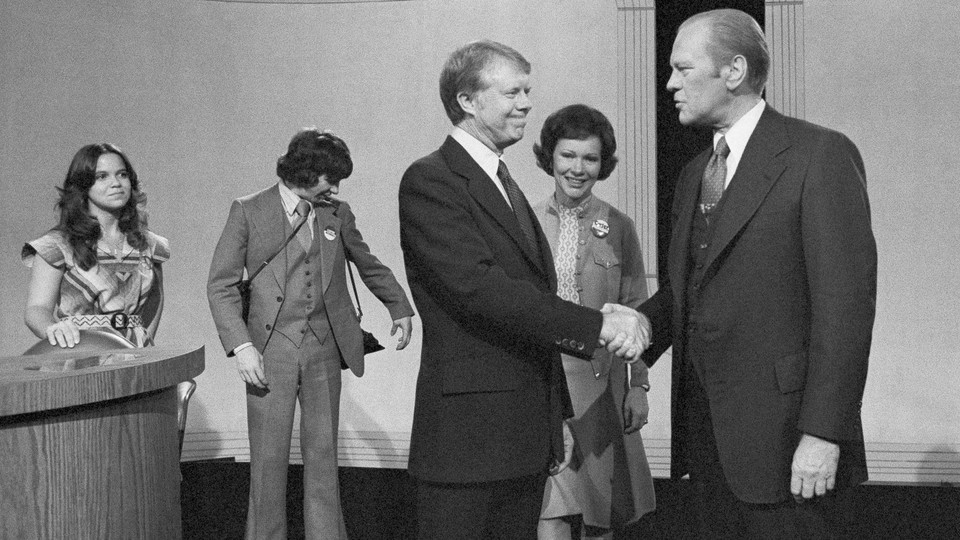

Searching for some precedent, any precedent, for those remarks, some journalists have turned to one of the more infamous gaffes in recent presidential history. During a debate against Jimmy Carter in October 1976, President Gerald Ford said, “There is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe and there never will be under a Ford administration.” Ford meant to say that the spirit of the people of Eastern European nations had not been crushed, despite Soviet occupation. But it seemed silly; journalist Max Frankel cut in after Ford’s remark, to ask incredulously what he had meant.

Ford’s remark has remained an exemplar of a boneheaded election gaffe. Here’s The New York Times Monday:

Not since 1976, when President Gerald Ford committed a major gaffe in one of his debates with Jimmy Carter, declaring that “there is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe,” has the issue of American support of Eastern European states, both those in NATO and those outside it, emerged as a major presidential campaign issue. It was enormously harmful to Mr. Ford, because his statement seemed to suggest that he did not understand the geopolitics of the region, which his staff denied.

In October 1976, during a debate with Jimmy Carter, President Gerald Ford insisted, “There is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe,” and then defended that assessment before an incredulous media. This strange and obviously untrue depiction of Eastern Europe, then firmly under Soviet control, did not reinforce any preexisting perceptions about Ford, a sitting president who had handled world affairs and was a clear anti-Communist. Nonetheless, it was considered one of the most damaging gaffes in the history of presidential politics, remembered for years afterward.

Scholars Julian Zelizer and Stephen Sestanovich have also invoked the moment recently.

Obviously it is true that the gaffe has endured as a symbol of Ford, a president whom history has recalled as well-meaning but clumsy both physically and verbally. But the idea that the remark was badly damaging to Ford is a pernicious misremembering, and the fact that careful outlets and writers are repeating it shows how deeply embedded the myth is. The myth’s endurance, despite little evidence that the moment hurt Ford’s campaign, exemplifies the reality that even the most famous gaffes usually have little effect on elections.

Ford battled a deep disadvantage in the 1976 election. He was an unelected president, having come to power when President Richard Nixon was forced to resign. Ford not only hadn’t won the job; he represented a party deeply stained by Watergate. In July of 1976, Ford trailed Democrat Carter by an astonishing 33 points in Gallup’s poll. But the president gradually chipped away at that lead, and in the last poll taken before the purportedly fateful October 6 debate, Ford reached 45 percent, nearly matching his high of 46 percent and trailing Carter by only two points.

In the two polls taken immediately after the debate, Ford sagged, but only barely—from 45 down to 42 and 41 percent. Whether that was a direct result of the “Soviet domination” comments or not is mostly beside the point, because he soon bounced back. In the final poll before the election, taken October 28 to 30, 1976, Ford actually led Carter. Unfortunately for him, that did not translate into a victory at the polls. But whatever the “Soviet domination” gaffe was, it shouldn’t be said to have destroyed Ford’s campaign.

Newton Minow, a former FCC chair who helped create the modern presidential debate, told me in November that Ford didn’t think so either.

“I talked to President Ford years later and was invited to talk at the Ford Library,” he recalled. “We had lunch with President Ford and Mrs. Ford, and I said, ‘How do you feel now, looking back?’ He said, ‘The press thinks I lost the election because of the debates. As far as I’m concerned the debates helped me! I started out 38 points behind. I ended up almost winning the election.’”

The lesson for Minow was that it’s easy to overstate the importance of gaffes: “Voters don’t expect a candidate to be perfect. What they want to know is: Is this guy trustworthy? Is he going to give me an honest answer?” Political scientists who have studied the matter tend to come to a similar conclusion about the importance of gaffes. In their book The Gamble, John Sides and Lynn Vavreck found that even Mitt Romney’s “47 percent” gaffe, portrayed by pundits on both sides of the issue as a turning point in the 2012 campaign that doomed Romney, found little evidence that it had hurt him at all. Romney was losing before the video of him speaking at private function was released, and he was losing by similar margins afterwards.

These gaffes were not, however, irrelevant. Romney’s 47 percent remark was newsworthy because it showed a candidate privately writing off nearly half of the electorate as “takers.” (Or so his critics said. His defenders insisted that was an uncharitable interpretation.) Ford’s “Soviet domination” remark was newsworthy because it showed the president as either flaky, in denial, or misinformed. Trump’s comments about Ukraine are significant as well, because they suggest that either the candidate is misinformed about current events in Ukraine, or else that he has chosen to break the world consensus on foreign policy and align himself with Putin’s regime. Either would be revealing about Trump as a candidate. The fact that gaffes don’t have much direct impact at the polls doesn’t mean journalists shouldn’t cover them. It just means they probably shouldn’t cover them as horserace stories.