This is the land of the lək̓ʷəŋən People, known today as the Esquimalt and Songhees Nations. As you travel through the city, you will find seven carvings that mark places of cultural significance. To seek out these markers is to learn about the land, its original culture, and the spirit of its people.

Created in 2008, The Signs of lək̓ʷəŋən consist of seven unique site markers that designate culturally significant sites to the Songhees and Esquimalt Nations along the Inner Harbour and surrounding areas. The markers are bronze castings of original cedar carvings that were conceptualized and carved by Coast Salish artist and master carver, Butch Dick with his son Clarence Dick Jr.

At 2.5 meters high and weighing close to 1000 pounds, the markers depict spindle whorls that were traditionally used by Coast Salish women to spin wool and were considered to be the foundation of a Coast Salish family.

The lək̓ʷəŋən People have hunted and gathered here for thousands of years. This area, with its temperate climate, natural harbours, and rich resources, was a trading centre for a diversity of First Peoples. When Captain James Douglas anchored off of Clover Point in 1842, he saw the result of the lək̓ʷəŋən People’s careful land management, such as controlled burning and food cultivation. These practices were part of the land and part of Lək̓ʷəŋən culture.

The development of a modern city makes it more difficult to experience the landscape that is home to the lək̓ʷəŋən. However, footprints of traditional land use are all around us, and this land is inseparable from the lives, customs, art, and culture of those who have lived here since the beginning.

The hills, creeks, and marshlands shaped the growth of the city of Victoria. There are messages in the landscape here; oral histories, surviving traditional place names, and the soil itself are all ancient stories waiting to be told. To follow the markers and visit these traditional places is to learn about the land, its original culture, and the spirit of its people. The traditions that were born here carry on today.

The lək̓ʷəŋən people’s art is traditionally used on internal house posts and for the decoration of household objects and clothing. This artwork became more scarce when western living supplies became available after 1842. Historically, the outward expressions of Lək̓ʷəŋən culture were more modest than some of the other coastal nations such as the Haida or Kwakwak’wakw. In fact, European travellers interested in native art would sometimes leave from Victoria unaware of the tradition in their midst.

Renaming of the Salish Sea

Songhees Point | p’álәc’әs

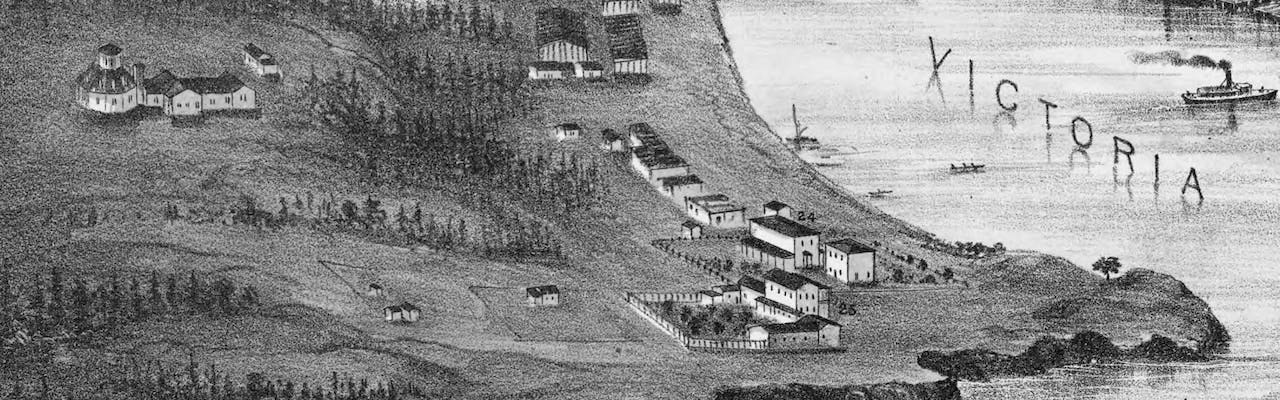

(Songhees point at the entrance to Victoria Harbour.)

PAH-lu-tsuss means “cradle-board.” Traditionally, once infants had learned to walk, their cradles were placed at this sacred headland because of the spiritual power of the water here. More recently, there was a settlement here, and subsequently a Songhees reserve, that traded with the fort on the opposite shore. Songhees Nation moved from this reserve to its current reserve in 1911.

Fort Victoria

(North side of Malahat Building on Wharf Street)

An imposing wooden fort, called Fort Camosun (and later known as Fort Victoria, the North side of the Malahat Building on Wharf Street), was built here by the Lək̓ʷəŋən men and women in exchange for trade goods. This marked a drastic change in traditional ways and traditional sustainable land use. A large forested area was destroyed to raise the fort.

Outside City Hall | skwc’әnjíłc

skwu-tsu-KNEE-lth-ch, literally “bitter cherry tree.” Here, willow-lined berry-rich creeks and meadows meandered down to the ocean, and paths made by bark harvesters bordered the waterways. The imprints of these creeks can still be seen in the uneven ground of the Market Square area. This was a creek bed that led back to the food gathering areas now contained by Fort, View, Vancouver and Quadra streets. Bark from the bitter cherry was used to make a variety of household objects.

Lower Causeway | xwsзyq’әm

(Lower Causeway of Inner Harbour)

Whu-SEI-kum, “place of mud”, marked wide tidal mudflats and some of the best clam beds on the coast. These flats were buried when the area was filled in to construct the Empress Hotel. This place was also one end of a canoe portage. The portage could be used to avoid the harbour entrance during heavy seas by cutting through from the eastern side of what is now Ross Bay Cemetery. Along the route, arrowheads and other stone tools are still found, reminding us that the lowlands were rich for hunting. When housing development began, the lower elevations were left for market gardens and nurseries until after the Second World War.

Beacon Hill | míqәn

(Off Circle Drive in Beacon Hill Park.)

The hill here is called MEE-qan which means “warmed by the sun”. This seaward slope was a popular place for rest and play – a game similar to field hockey, called Coqwialls, was played here. At the bottom of the hill was a small, palisaded village that was occupied intermittently from 1,000 until approximately 300 years ago. The settlement was here for defence during times of war, and it was also important for reef net fishing. The starchy bulbs of the wildflower, Camas, were an important food source gathered in this area. The hill here is also known as Beacon Hill.

Royal British Columbia Museum | q’emásәnj

(Corner of Government and Belleville Street)

Corner of Government and Belleville Streets The objects, carvings and art of the Lək̓ʷəŋən people are unique. The Lək̓ʷəŋən have loaned many cultural objects from this area to the museum so that the traditions can be shared as we share the land. Some of these objects are on display inside.

Laurel Point

The carving here marks a nineteenth century First Nations burial ground. Small burial shelters with different carved mortuary figures, including human figures, were placed in front of the graves and stood here until the 1850s. No traditional name is known for this area.