PORTLAND, Maine — Kids gather to start another school day, full of energy and anxious chatter. It's a common scene everywhere. Except here the chatter might be in four different languages, and the bus stop is in a hotel parking lot off busy Route 1 in South Portland.

These children are some of the latest arrivals in an uptick of immigrants seeking asylum in Maine.

More asylum-seekers are coming to Maine now than during the summer of 2019 when Portland opened up the Portland Expo to house nearly 450 of them. Currently, 513 asylum-seekers are in temporary housing.

The difference? These refugees are not coming en masse, but in smaller groups and in steadily increasing numbers.

In October 2020, eight families — 32 people — sought shelter in Portland. By October 2021, that number had risen to 45 families comprised of 145 people.

They are not coming to Maine from the same place or through one organization, but all are escaping danger in their homelands. Most are from the Democratic Republic of Congo or Angola, though a few Haitians are also beginning to arrive.

Their journeys are long and complicated. Some have been traveling for years. Their stories are similar to that of Prince Pombo, who was part of the wave of immigrants from Congo that landed at the Expo.

"I was jailed for eight months," he said. "I flee from jail to Angola, flee from Angola to Brazil. From Brazil with wife and daughter, I come here. We spent four months walking to get to America."

Two years after he arrived, he worked for L.L. Bean, supporting his wife and two children.

He teaches French in Freeport — it's one of the four languages he speaks. Pombo spends at least two days a week interpreting for asylum-seekers just arriving in this foreign, confusing land.

"It's so hard. I know what it looks like to get someplace that you’re not familiar with the language, culture, weather, the systems," Pombo said.

Perhaps they come because they have heard about the quality of Portland services or that other African families have settled here. Portland officials say most New Mainers in the city list Portland’s Family Shelter as their final destination.

But there’s a problem: There’s no more room. The family shelter is full. Portland has contracted with four hotels in South Portland and others in Portland and Old Orchard Beach, to house people waiting to get into the shelters, be they immigrants or the growing number of homeless transients.

Once they get spots in the shelters, they can eventually be placed in permanent housing. The city is trying to group the clientele so people with substance abuse issues are not next door to families. But that is not always possible.

However, one of the hotels on Route 1 in South Portland is earmarked for families. It is constantly at capacity with immigrants.

The hotels are paid by general assistance, which right now is being reimbursed for the hotel stays by the Federal Emergency Management Agency as part of a special COVID program now extended through the end of March.

While the hotels may not get the rates they would typically get, especially during the summer, every room is full every night.

Steve Leonard, a regional manager of hotel chains, said, “The folks we have over here are wonderful people.”

He said management is committed to seeing them through to the end, though no one knows how long that might take.

"You see things you never saw before. We’re human. We all have hearts. Looking around here ... this is no one’s fault. We have to help each other," hotel manager Michelle Sandman said.

Sandman never imagined her work in the hospitality industry would include all she’s doing now.

"We’ve learned to speak other languages. We are gathering clothing, summer and winter, needs for babies, like diapers. We basically contacted everyone we can," she said.

When the Expo was open, all the service providers could come to one place. Asylum-seekers are now spread out all over the state, and those involved say coordinating services has been a real challenge.

Sandman, with donations from various agencies and organizations, stocks a constant supply of free snack food in the lobby. Still, she must convince the immigrants, who’ve had so little for so long, that the food will still be here tomorrow.

"I stand in the lobby with the translator. I have to say, 'There is plenty of food. You can come back tomorrow to get some more, but let's make sure everyone gets some,'" she said.

But food is hardly the only immediate need.

"They arrive here with nothing. Nothing. A lot of these immigrants arrive in the dead of winter in tank tops and flip-flops," she said.

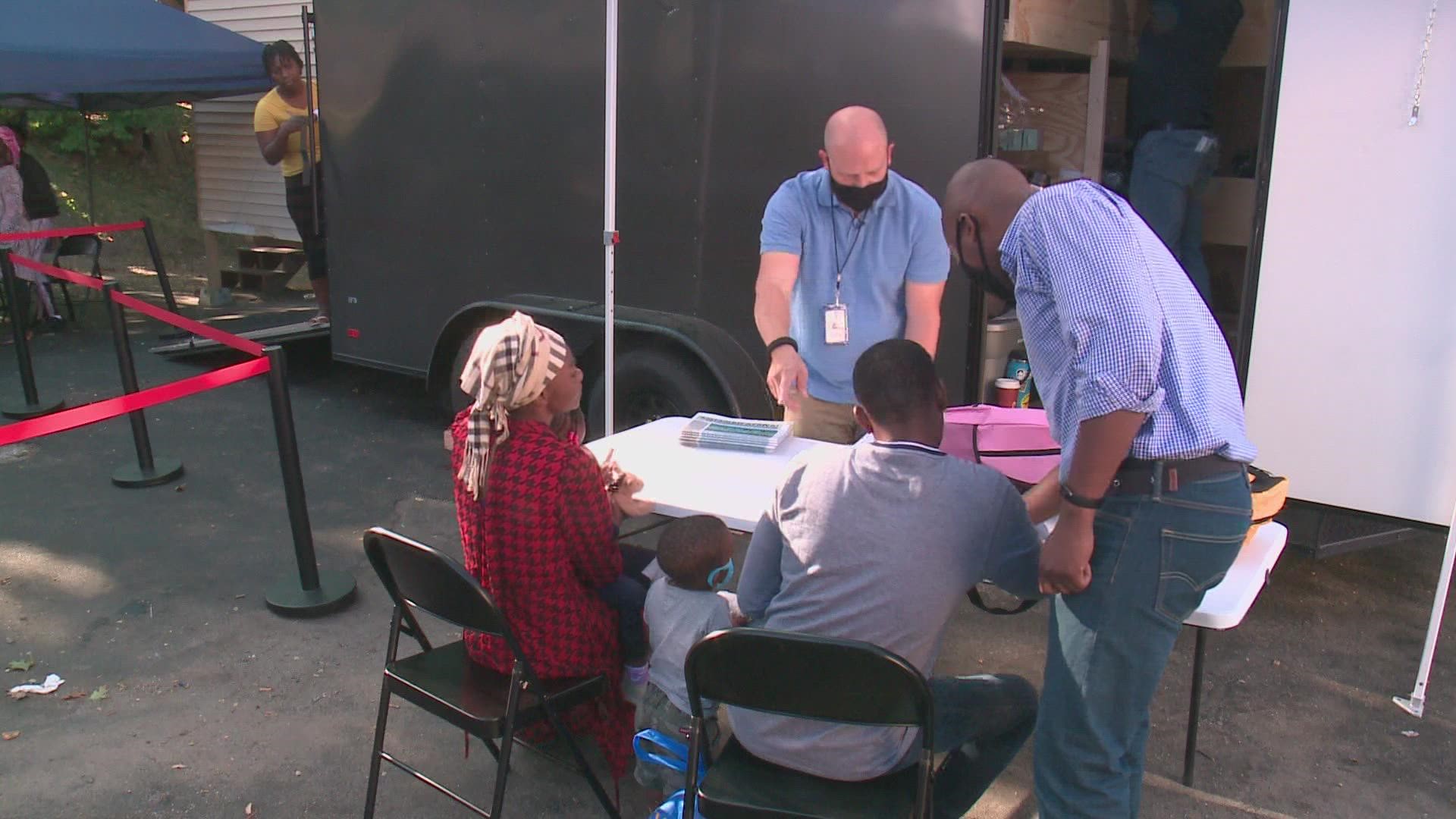

That is where Operation Outreach comes in. Firefighter and paramedic Josh Pobrislo is South Portland’s local health officer one day a week. He started this program and wrote grants to pay for a trailer, built it out, and stocked it with supplies for asylum-seekers and people experiencing homelessness.

He and his team of volunteers have been making the rounds to these hotels since last summer. The needs are all-encompassing and constant, much like what he saw growing up on Native American reservations.

"It hurt when I couldn’t help them, so when I saw this, I felt compelled to do something about it," he said.

In the back of the trailer, there is a mobile clinic where paramedics screen for health problems.

"A common one, especially with little ones, is upset bellies because the food we are offering, or they have access to, doesn’t work well with little tummies," Pobrislo said.

In broken Spanish, which many asylum-seekers picked up on their trek through Central America, Pobrislo attempts to help them navigate a complicated system of immigration, applications, school registration, and transportation.

He said the lack of coordination of services from more than 50 agencies and organizations is frustrating "because there are so many agencies and not one direct lead. It makes those conversations difficult."

As an example, the family shelter overflow is on Route 1 in South Portland. Pobrislo said the grocery vouchers they are given can only be used at the Hannaford on Forest Avenue in Portland, but they have no transportation to get there.

"They don’t want to be sitting here doing nothing. They all have skills and would like to work," he said.

They are not allowed to work until the federal government permits them to do so.

And the rooms, while a welcome respite from life on the road, are not equipped for families living here for this long. Portland said, on average, families are here five months though some have been here nearly a year.

It’s hard to cook for a family with just a microwave and refrigerator. At night, families as large as seven crowd beds, pull-outs, and portable cribs. During the day, they congregate in what has become their asphalt community center: the parking lot.

This is where Josh sets up shop.

"What he’s done is incredible,” said Rob Couture, the EMS Coordinator with the South Portland Fire Department and a member of Operation Outreach.

While he’s encouraged by recent efforts to increase communication among agencies, Couture is concerned because the grant money for Operation Outreach is running out, and those agencies will have to gear up to fill the gap.

"We took on a large population of these folks. We didn’t have service to deal with them since we haven't had this population in these numbers in our community," Couture said.

And housing the influx of asylum-seekers and people experiencing homelessness coming through Portland is impacting South Portland city services.

"We've had residents who became homeless through no fault of their own, who needed placement, and we unable to find anything because we were at capacity. It was me and my staff calling every hotel from Freeport to Sanford trying to find a place for somebody, which means a SoPo resident would end up in another municipality," Kristin Barth, director of South Portland's general assistance office, said.

Schools are also feeling the strain, as the number of new students considered homeless because they live in temporary housing has skyrocketed.

South Portland Superintendent Timothy Matheney said the district has received federal grants to help with the cost of transporting, translating, and providing English classes for these students. He is quick to add that the environment among the students has been welcoming and that "one of the things that makes South Portland schools so special right now, is the opportunity to go to class with students from all over the world."

There is also stress on public safety. Police calls to two hotels near the Maine Mall housing mostly transient people experiencing homelessness are up 300% to 1,500%, as are complaints of shoplifting, drug use, and fights in the area.

At the two hotels housing asylum-seekers on Route 1, most of the calls are for paramedics. However, the number of those calls is up as well, 200% to 400% since 2017.

That led the South Portland city manager to issue letters to all the hotels saying they need to figure out how to reduce the number of 911 calls or risk losing their licenses to operate.

There have also been meetings between South Portland and Portland city officials about how to address these strains. City leaders on both sides said they are working together on solutions to address the increase in police calls including more on-site oversight and more education about when to call 911.

What everyone wants here is for these populations to be placed in affordable housing. But where?

"We cannot build it fast enough," said Dana Totman of Avesta Housing, a nonprofit affordable housing organization.

He said supply shortages caused by COVID have slowed the construction of new affordable housing. What used to take 12 months to build now takes 18 months. And it costs more. The pandemic has also slowed the turnover of existing units. People are just staying put.

Totman said, "I’ve been doing this a long time, and I’ve never seen it this bad. We get 50 calls a day from people looking for housing. We can only help 2-3 a day. It’s sobering and challenging."

That leaves few permanent housing options for new arrivals. Totman added, "I think there is light at the end of the tunnel, but the tunnel is too long. It’s going to take several years to increase the supply of affordable housing."

Leaders in Portland and South Portland agree that this is both a city or regional issue and a statewide issue. While federal funding is helping address some of the needs, like paying for the hotel stays, the cities say they need help from the state in finding places for asylum-seekers and people who are homeless to live.

"This affects the whole community. Hopefully, we can work together to make a difference, and things will get better," Couture said.

There is hope that even more federal funding will be coming to Maine. Federal officials will be conducting a site visit to see the housing provided for asylum seekers. City leaders are hoping that Maine could be elevated to Tier 1 status, making the state eligible for money earmarked for meeting the needs of asylum seekers.

In the meantime, the Portland area community is rallying around asylum seekers. Portland's St. Brigid School will be delivering coats, basketball and soccer balls, and multicultural dolls to the Overflow Family Shelter at the end of this month. They had to stop taking donations when their storage room got too full.

Pobrislo and his team are doing all they can to meet the most pressing needs of traumatized families seeking safety in a new world.

"What they went through and haven’t processed yet ... How it will manifest later in these kiddos ... it breaks my heart, breaks my heart," he said.

Prince Pombo, who was himself in this same boat two years ago, reminds everyone that "this is about human beings. We are trying to save human beings," he said.