Introduction

The experiences of frontline workers during the pandemic offer lessons beyond the

public health threat.

They point to a general

undervaluing of work that is sometimes deemed critical or essential, and a broad lack of worker power to improve conditions in their workplace.

The arrival of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus which causes COVID-19) in the United States in early 2020 led to massive social and economic upheaval. The rapid spread of the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated drastic public health measures and resulted in some of the most dramatic economic shifts in the last century. The pandemic simultaneously created new

challenges and exacerbated existing ones. It both required the prompt adoption of innovative policy solutions and refocused attention on policies that had long been identified as necessary to improve working conditions in the US.

State of Working Maine 2021 details the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on working Mainers and examines the effectiveness of policymakers’ responses. It illustrates the ways in which policymakers must learn from the pandemic in crafting new policy that improves conditions and supports, and the opportunities which are presented in this moment of rebuilding to create a fairer economic system that works for everyone — not just those at the top. In particular, by placing additional strain on an already-disparate system, the COVID-19 pandemic worsened existing challenges for women and people of color.

The magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US cannot be overstated. The first US case was recorded in Washington state on January 21, 2020. One year later, more than 24 million Americans had tested positive for the disease, of whom almost 400,000 had died. The pandemic’s impact in Maine was smaller, but still dramatic. The first case of COVID-19 in Maine was confirmed on March 12, 2020; within a year, almost 47,000 Mainers had tested positive for the disease and 723 had died. Nor has the development and widespread rollout of a vaccine against the COVID-19 completely removed the threat. As of October 2021, the total number of deaths in the US had reached 700,000, more than 1,000 of which were Mainers. An extremely deep recession accompanied the global pandemic.

Over the spring and summer of 2020, the US saw the biggest decline in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the highest increase in unemployment since the Great Depression. In Maine, state GDP contracted 11.5 percent between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2020.1 In April 2020, approximately one in eight people who had a job at the start of the pandemic was out of work.2 And while the economic situation has improved significantly at both the national and state levels since the depths of the recession, due in large part to mitigating actions taken by the federal government, GDP and employment remained below pre-pandemic levels in September 2021.

The pandemic created and extended the economic recession in two important ways. The prevalence of the virus itself impacted Mainers’ spending habits as they chose to stay home to reduce exposure to the virus. And the extremely infectious and deadly nature of COVID-19 required public health measures to curb the spread of the disease, including guidance to stay at home, mandatory closures of non-essential businesses, and restrictions on interstate travel. These measures were successful in slowing the initial spread of COVID-19, at the cost of some economic activity.3 Notably, however, research also shows that over the longer term, states with stricter containment measures saw a faster recovery in employment and other economic activity.4 In other words, containing the virus remains imperative for economic recovery.

The pandemic and associated recession impacted Maine workers in several ways. A substantial number lost their jobs. Others were asked to continue working in so-called “frontline” or “essential” occupations, which put them at added risk of infection for COVID-19. Mainers have also felt collateral impacts such as a lack of available child care. In some cases, lawmakers enacted policies that have mitigated these effects successfully. In other cases, there is a clear need for further structural change to improve state and federal responses to public health emergencies.

Greater Supports Needed to Protect Frontline Workers

In general, Mainers who

worked in-person were

50 percent more likely to

contract COVID-19 than

remote workers.

As of September 2021,

Black Mainers were more than twice as likely to have contracted the virus as white Mainers.

How workers fared during the COVID-19 pandemic depended greatly on whether they were able to work remotely from home or were required to continue in-person work. As part of the efforts to reduce exposure to SARS-CoV-2, public health measures dictated that Mainers stay home as much as possible, which included reducing exposure at workplaces by limiting in-person work. In the spring and summer of 2020, between one-quarter and one-third of Maine workers worked from home due to the pandemic.5 By June of 2021, this proportion had fallen to 10 percent, but this was still a much higher number than people who worked remotely before the pandemic.

Throughout the pandemic, some groups of in-person workers were referred to as “essential” or “frontline” workers. Neither term has a clear or consistent definition. The US Centers for Disease Control refers to a list of “critical infrastructure” workers compiled by the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS). This list encompasses more than half the US workforce. Similarly, Maine’s Department of Economic and Community Development created a list of businesses deemed “essential” and allowed to continue operating in the first weeks of the pandemic, when others were forced to close. Though slightly different from the US DHS guidance, the Maine list of essential businesses also included around half of the state’s workforce.

Despite this big shift, a clear majority of Maine workers continued to work in-person throughout the pandemic (see Figure 1). Many worked in occupations or industries in which it was impossible to work remotely — grocery store workers, restaurant servers, and building cleaners, for example. In other cases, their workplace may have been ill-equipped for remote work.

Public health officials encouraged remote work to reduce the spread of COVID-19, and the available data show that in-person work was indeed significantly more dangerous during the pandemic (see Figure 2). In general, Mainers who worked in-person were 50 percent more likely to contract COVID-19 than remote workers.

Furthermore, data at the national level and from other states show that certain in-person occupations and industries were especially risky. Studies from California, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Utah, and Washington found especially high numbers of COVID-19 deaths among workers in agriculture, health care, manufacturing, warehousing, grocery stores, and bars and restaurants, as well as cleaning and maintenance staff across multiple industries (see Appendix A).

Frontline jobs typically pay low wages and are less likely to offer affordable health care benefits. Workers in many of these high-risk, frontline industries share certain characteristics. They are more likely to be women and people of color (see Figure 3). This is no coincidence. The segregation of women and people of color into low-wage work with less access to benefits is the result of centuries of historic and current-day discrimination in the labor market.6

As of September 2021, Black Mainers were more than twice as likely to have contracted COVID-19 as white Mainers, with the disproportionate concentration of Black workers within high-risk industries probably being a significant factor in the increased prevalence of the virus.7 A national study of Hispanic Americans found factors such as age, pre-existing conditions, household composition, and access to health care could not explain disproportionate COVID-19 infection rates among Hispanics. The study’s authors point to workplace exposure as the most likely factor.8

The risks for workers in these industries are partly dictated by the nature of the work itself; most involve high levels of contact either with members of the public or coworkers. However, these risks were mitigated by those employers who issued personal protective equipment (PPE) and sanitizing fluid, enforced policies such as social distancing, and reduced staffing and customer capacity.

During the pandemic, governments left the decision to employ protection measure almost entirely to the discretion of employers. The federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration did not adopt mandatory safety procedures for employers and only issued advisory guidance in 2021. The state similarly lacked enforcement, partly due to a scarcity of funding for the relevant agencies.9 The Maine Department of Economic and Community Development only issued 70 citations for COVID-19 safety violations during 2020.10 Past experience suggests this low number is more likely due to a lack of enforcement than widespread public compliance.

As State of Working Maine 2019 showed, state action on issues such as wage theft and workplace discrimination is far smaller than the frequency of reported violations by workers themselves.11

A large survey of workers in Massachusetts found that in several high-risk industries, many employers failed to implement basic safety protocols. While three-quarters of Massachusetts in-person workers received PPE from their employer, this was only true for 58 percent of buildings and grounds workers and 59 percent of food service workers. And while two thirds of in-person workers worked in places that implemented social distancing, the same was only true of 34 percent of buildings and grounds workers and 51 percent of transportation and moving workers.12 While Maine data are not available, it is plausible that similar practices were used in the state.

Another important preventive measure against infectious disease in the workplace, including COVID-19, is allowing employees to take paid sick leave. Previous studies have shown that provision of paid sick time reduces the spread of influenza,13 and early studies find a similar effect on the spread of COVID-19.14 Yet many of Maine’s workers at highest risk of contracting COVID-19 were unable to take any paid sick time if they contracted the disease.

The paid time off law passed in Maine in 2019 excluded 15 percent of Maine workers who work at small businesses, the very Mainers who were least likely to already have access to paid sick time through their employer.15 Maine’s new law, which took effect in January 2021, also only gave Mainers up to five days of paid leave (for full-time workers). In contrast, Mainers exposed to COVID-19 were asked to isolate for 14 days. Longer periods of leave such as this are best addressed with a paid family and medical leave program (PFML). While nine states have enacted PFML laws, Maine has yet to do so.

The experiences of frontline workers during the pandemic offer lessons beyond the immediate public health threat. They point to a general undervaluing of work that is sometimes deemed critical or essential, and a broad lack of worker power to improve conditions in their workplace. Elected leaders should implement the following policy prescriptions to improve conditions for frontline workers now and in the future:

- Increase the scope of Maine’s paid time off law to include all workers. Create a statewide paid family and medical leave law for longer-term sicknesses.

- Empower workers through greater workplace protections, including allowing workers to take their employer to court if their employer violates their workplace rights.16

- Encourage and facilitate the formation of unions in the workplace. This can include removing the prohibition on unionization by agricultural workers in Maine. In general, unionized workplaces have better safety records.17 Studies in Canada18 and the United Kingdom19 found that unionized workplaces were more likely to allow remote work, provide PPE, and implement other safety measures.

Furthermore, lawmakers should recognize the risks faced by frontline workers. Increasing the minimum wage to $15 per hour by 2025 would increase wages for 148,000 Mainers, including many in the highest-risk

frontline occupations. And to phase out the lower minimum wage for tipped workers would provide a muchneeded raise to 16,000 workers most impacted by the pandemic and recession.

Program Improvements Needed to Adequately Support Workers

The onset of the COVID-19

pandemic exposed many

flaws in our economic system and made it clear just how economically precarious many Maine workers were.

The arrival of the pandemic itself was unexpected. Much of the resulting fallout was not.

In April 2020, Maine’s unemployment rate surged

from a record low of around 3 percent to a seasonally adjusted 9.1 percent, the highest rate on record in almost 50 years of state-level employment data.20

But this huge surge in unemployment did not tell

the whole story. Even in “normal times,” many Mainers who are out of work are not included in the

unemployment numbers because they are unable to look for work. In the pandemic, this phenomenon was even larger, with many Mainers unable to seek work due to COVID-19 and excluded from unemployment figures.

What’s more, a significant proportion of Mainers who reported being employed or at work in official labor force surveys were on unpaid furloughs as their businesses closed temporarily for public health reasons (see Figure 4). Once those Mainers were considered, the actual number of people who were unemployed is far higher than official statistics suggest. For example, in May 2020, the official unemployment rate (not seasonally adjusted) was 8.7 percent. But if Mainers on unpaid furloughs and those who had dropped out of the labor force were included, the unemployment rate would have been a staggering 21.5 percent.

Job losses were concentrated among workers with low income, and especially women and people of color. Many of the layoffs and furloughs occurred in sectors that were also deemed “essential” during the pandemic. For example, hospitals laid off many of their staff as they delayed accepting patients for nonemergency care, and restaurants running at reduced capacity or with takeout-only service downsized their staff accordingly.

As the economy has begun to recover in 2021, employment numbers for these groups who are most impacted have also been slowest to bounce back. Mainers in high-wage industries are more likely to have returned to work, as are men and white Mainers (see Figure 5). These two trends are partially correlated, since, due to discrimination and barriers to opportunity, low-wage industries are more likely to be staffed by women and Mainers of color. However, research from past recessions also finds that discrimination plays a big role in preventing these individuals from being rehired as fast as their white, male counterparts.21

Federal aid programs partially mitigated the potentially devastating financial impact of the widespread loss of employment. The Census Bureau’s report on poverty in the US in 2020 found that although the official measure of poverty increased in 2020, the “supplemental poverty measure” — that includes the impact of government aid — actually fell relative to pre-pandemic levels.22 In other words, federal aid was broadly successful in overcoming the economic hardship of the pandemic.23 In particular, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act, enacted in March 2020, provided Americans one-time relief payments of up to $1,400 each, and created new Unemployment Insurance (UI) programs to assist Americans without jobs who would not otherwise qualify for UI. Congress also authorized additional payments to UI recipients of up to $600 per week, known as Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation, to ensure that benefits for workers who were laid off or furloughed were at least as large as their regular earnings.

The new federal programs greatly increased Mainers’ eligibility for, and receipt of, UI payments. Before the pandemic, just one in four Mainers qualified for UI. During the pandemic, it appears that a substantial majority of out-of-work Mainers qualified for one of the UI programs. Between May and July 2020, the total number of paid claims each month averaged 67 percent of Mainers who were out of work or on unpaid furlough during the same period — much higher than before the pandemic but still allowing many workers to fall through the cracks.24 A similar disparity can be found in responses to surveys in 2021. During this period, 15 percent of Mainers who applied for UI benefits did not receive them (it’s not clear how many of these were rejections based on ineligibility and how many were applications that weren’t processed correctly). Another unknown portion was likely eligible but never applied.25 This disparity was especially acute for Mainers of color, who were twice as likely to have had UI claims denied in this period.26

In other words, almost one-third of Mainers of color applied for, but were denied, unemployment compensation. Some of this could be attributable to linguistic barriers, since Mainers of color are significantly less likely to be native English speakers than white Mainers.27

While the creation of the new UI programs provided essential relief to tens of thousands of Mainers, the volume of applicants overwhelmed Maine’s existing resources such as claim adjudicators, phone lines, and computer infrastructure. Applicants faced a number of well-documented barriers during the first weeks of the program, but even after these issues were resolved with more staff and software fixes, many unemployed Mainers still missed out.

An additional new program authorized by the CARES Act with the aim of keeping workers paid during shutdowns and furloughs was the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), which provided forgivable loans to small businesses to spend on operating expenses and employee payroll. While PPP had successes — for example, keeping some small businesses and their owners afloat and preventing some layoffs28 — its impact on employment appears to have fallen short of the stated goal. Between May and August 2020, small businesses in Maine received $2.3 billion in forgivable loans,29 an amount that could potentially support the paychecks of 250,000 workers.30 However, Maine data show that on average during that period, just one in eight furloughed Mainers received some form of pay from their employer (including some who worked for large companies ineligible for PPP loans). What’s more, an average of 63,000 individuals each month were out of work due to the pandemic and received no pay.31

National research on the impact of PPP loans, focusing explicitly on eligible companies, finds that while loans were issued to employers with pre-pandemic payrolls of $53.6 million, the actual number of jobs saved by the program was much smaller, with estimates ranging from 1.3 to 7.7 million.32 Other examinations of the program have found that women and people of color were less likely to receive loans than white men who owned similar businesses,33 partly due to discrimination by lenders34 and a lack of preexisting relationships.35

In addition to long-term disruptions in employment caused by business closures or shutdowns, Mainers also faced temporary disruptions due to either contraction of COVID-19 or exposure to the illness which required a two-week quarantine period. The lack of adequate paid time off or paid family leave policies (see part 1) meant that between April and December 2020, two-thirds of Mainers who had to take time off to care for themselves or a family member with COVID-19 did so using unpaid leave, while another 8 percent received only partial pay while on leave.36

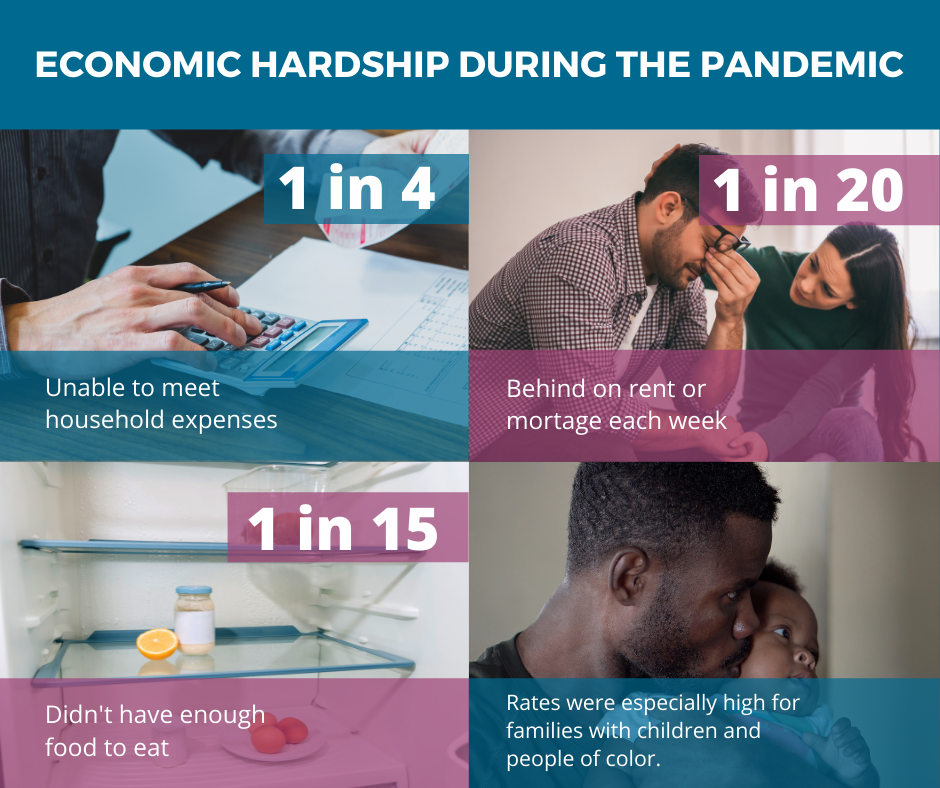

While federal programs alleviated hardship for many Maine families, the holes in programs like UI and PPP meant that significant numbers still suffered economically during the pandemic. On the one hand, official data from the Census Bureau’s supplemental poverty measure found that federal programs lifted millions of Americans out of poverty who were hard hit by the pandemic.37 On the other, results from the Census Bureau weekly household pulse between May 2020 and March 2021 showed that more than one in four Maine adults were unable to meet their regular household expenses each week. Other results from the survey showed significant levels of food and housing insecurity as well. On average, one in twenty households was behind on their rent or mortgage each week, and one in fifteen didn’t have enough food to eat. These rates were especially high for families with children and for people of color in Maine (see Figure 6).38

While they did not completely offset the economic hardships of the pandemic, the expansion of several safety net programs doubtless reduced hardship and suffering. The federal government temporarily expanded the eligibility and benefit amounts for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the National School Lunch Program, both of which likely reduced hunger among the poorest Mainers. Maine lawmakers have voted to continue the provision of universal free school meals after the end of the public health emergency, using state dollars. Provided long-term funding can be secured, this will boost educational outcomes for students with low income as well as provide food security.39

Similarly, Maine’s expansion of Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act ensured there was relatively little disruption to Mainers’ access to health insurance. The number of Mainers aged 18-64 with health insurance increased by almost 30,000 between 2019 and mid-2021.40 Research at the national level confirms that public insurance coverage such as Medicaid was responsible for preserving Americans’ access to health care, and that residents of states which have expanded Medicaid eligibility suffered the least disruption in insurance coverage.41

Policymakers must learn from the COVID-19 pandemic and recession and ensure nobody is left behind in the future:

- Continue to improve Maine’s unemployment insurance program. Recent reforms will help, as will the implementation of a new navigator program to help Mainers access benefits for which they are eligible. Potential further improvements should include increasing the replacement wage rate for workers with the lowest income.

- Overhaul unemployment insurance law at the federal level to either implement nationwide reforms or to allow states more flexibility than currently exists. For example, the program would function better if benefit lengths were tied to labor market conditions, with more weeks of payments available when work is hardest to find.

- Commit to fully funding universal free school meals in future budgets to reduce child hunger thereby improving students’ educational outcomes and increasing chances for them to meet their potential.

- Continue to support expanded Medicaid eligibility and explore ways to increase eligibility. For example, the Maine legislature recently restored Medicaid eligibility to children and pregnant women who would otherwise be disqualified due to their immigration status. Restoring eligibility to immigrant adults would close a critical gap in coverage.

Investments in Child Care, Equity, and Reforms to Workplace Practices Needed to Ensure Full Recovery

For Maine’s economy to recover from COVID-19, workers must have the opportunity to return to

jobs that ensure they can provide for themselves and their families.

This can be achieved through laws that improve working conditions and programs that remove barriers to work.

Despite the rapid development of several vaccines against COVID-19, and an initial decline in the virulence of the pandemic, the recovery of jobs and economic security has not been as rapid as some had hoped. The emergence and spread of the more infectious delta variant of the virus has certainly played a role in holding back the recovery, but even before the delta variant was widespread in the US, there were signs of a slowing recovery.

Workers with low wages not only experienced more layoffs than middle- and upper-wage workers during the pandemic, but the recovery of jobs in these sectors has been much slower. As of June 2021, employment in low-wage industries in Maine was still 8 percent below pre-pandemic levels (see Figure 5). Additionally, structural inequalities in career opportunities and hiring practices have caused additional barriers and longer re-entry times in the workforce for women and people of color as compared to white, male Mainers (see Figures 6, 7).

Access to affordable child care remains a significant barrier for a return to work for many, especially women, who often shoulder a disproportionate amount of caregiving. Even before the outbreak of COVID-19, child care was in short supply and, correspondingly, expensive in Maine. In 2019, one in ten Maine children had no out-of-home child care given a shortage of providers. The problem was especially acute in Maine’s more rural second congressional district, where one in six children who need care do not have access to a provider.42 In addition to capacity, cost presents an excessive burden for many families. As of 2021, the typical cost of care for an infant was just under $1,000 a month,43 and for an estimated 89 percent of Maine families, the cost of care exceeds the official affordability standard of 7 percent of family income.44 At the same time, recruiting and retaining caretakers has been difficult when wages in the industry are so low. In 2020, the typical hourly wage for child care workers was just $13.84 per hour — only slightly above the statewide minimum wage of $12 per hour.45

The COVID-19 pandemic and recession have only made this shortage more acute. While the number of child care providers has remained stable during the pandemic,46 90 percent of child care facilities saw reduced capacity, and half either laid off staff or had staff leave.47 At the same time the need for child care increased as schools were closed, and many working parents faced the unprecedented challenge of assisting or caring for school-aged children who were learning virtually outside of the classroom. In the face of these changes, some Mainers, especially women, were forced to make the decision to reduce their hours or quit their jobs to care for their children. As of August 2021, 25,000 Mainers were out of work due to a lack of child care, of which 22,000 were women.48 Put another way, one in eight mothers are out of the workforce because they can’t find child care, as are one in thirty-three fathers. Without an expansion of child care services in the state, these Mainers will be left behind in any recovery, as they will be severely limited in their ability to take good paying jobs that fit their skillset on the schedules that work for them.

As part of its “jobs and recovery plan,” the state of Maine has committed to increasing child care availability for families with low income through more funding to the Child Care Subsidy Program, and additional grants to providers.49 However, the long-term problem of child care requires a long-term solution. Ultimately, public subsidization of child care is the only way to make care more affordable while adequately compensating caregivers. The forthcoming federal American Families Plan includes a number of provisions which may help achieve this goal, including direct subsidies for parents, expansion of the child care dependent tax credit, and direct payments to providers for infrastructure and training.

As State of Working Maine 2020 detailed, Mainers of color regularly face barriers in the labor market rooted in racial discrimination.50 These include longstanding structural barriers, such as the intergenerational poverty caused by policies which excluded people of color from historic assistance programs like the GI bill and homeownership programs of the 20th century. The legacy of historic discrimination means people of color are less likely to own homes or businesses in Maine and have less access to resources such as a college degree or quality health care, which are dependent on income.

However, beyond these historical legacies, the evidence is clear that some present-day discrimination by employers and others keeps Mainers of color excluded from the full benefits of the economy. For example, State of Working Maine 2020 lays out the ways in which Black, Latino and Indigenous Mainers are more likely to be forced to take lower-paying jobs despite their level of educational attainment, to be underpaid even when doing similar work, and to be denied employment than similar white applicants.

Combatting these trends and ensuring full employment for Mainers of color require strong anti-discrimination enforcement by state agencies, implementation of new laws such as Maine’s recently passed “ban the box” law, which prohibits employers from asking about criminal history on job applications, and ensuring career readiness programs are accessible and accommodating to Mainers from all backgrounds.

Beyond specific barriers for people, certain industries have seen significant difficulties in rehiring workers after the pandemic. In particular, the restaurant and hotel sectors have some of the largest shortfalls in employment compared to pre-pandemic levels. For example, while total payroll employment in June 2021 was down 2 percent compared to the same time in 2019, employment in food services and accommodation was down 12 percent and 34 percent, respectively.

Research shows that the expansion of UI payments did not substantially reduce job-seeking.51 Similarly, cutting UI benefits has not increased employment.52 Nor does it appear that lack of employment is due to lack of demand from consumers. Taxable retail sales data from Maine revenue services show that even while payroll costs are down for these industries, sales are substantially higher than before the pandemic.53 Collectively, Maine’s hospitality sector sales were $171 million (16 percent) higher in June and July 2021 than in the same period in 2019”.54

Several signs point to poor working conditions and low wages as hindering hiring in Maine’s hospitality industry. Multiple national surveys have shown that Americans in general are reconsidering employment options during the pandemic, especially if they were laid off.55 For State of Working Maine 2019, MECEP surveyed Maine workers about the elements they most valued in a job. The top priorities for workers were good wages (89 percent of workers said these were “extremely” or “very” important); quality, affordable health care (86 percent); predictable schedules (80 percent); paid vacation (79 percent); paid sick time (76 percent); and paid family and medical leave (70 percent). On each of these measures, hospitality employers fall short, with few benefits, unpredictable schedules, and low wages.

A survey of Mainers receiving unemployment payments in July 2021 showed similar concerns. Survey respondents cited barriers to return to work including lack of opportunities matching their skillset (34 percent); COVID-19 health risks or concerns (31 percent); insufficient wages (29 percent); lack of benefits (15 percent); unpredictable schedules (13 percent); and lack of long-term positions (11 percent).56

For Maine’s economy to recover from COVID-19, workers must return to jobs that ensure they can provide for themselves and their families. Policymakers can facilitate recovery through laws that improve working conditions and programs to remove barriers to work:

- Implement a livable minimum wage of $15 per hour by 2025. This would increase wages for 148,000 Maine workers, including 44 percent in frontline occupations with the highest risk,57 and implicitly recognize the risks faced by frontline staff. Additionally, phasing out the lower minimum wage for tipped workers would provide a raise to 16,000 workers most impacted by the pandemic and recession.58

- Reform scheduling practices through “fair workweek” laws to provide stability and predictability to the lives of workers with low wages. Too many Mainers are at the whim of their employer for their working hours, and, by extension, their weekly income.

- Institute a statewide paid family leave program and ensure working Mainers have the flexibility to care for themselves or a loved one if they fall sick. This would particularly benefit Mainers who regularly care for a child or elderly family member and must choose between this care and the ability to work.

- Establish a widespread system of publicly subsidized child care — the only way to create a universally-affordable child care system for all Mainers. The status quo has created a care system which is too expensive for many parents, even while chronically underpaying staff. Public subsidies could boost wages for providers while cutting costs for parents.

- Invest in programs to facilitate hiring people of color and immigrants, who still face barriers in Maine’s labor market rooted in discrimination. State career centers and workforce development organizations should offer programs to employees to help them best utilize their skills and experience. The state should also encourage employers to reform hiring practices to create opportunities and eliminate discrimination.

- Enforce existing anti-discrimination laws through increased penalties for violations, and increase resources at the state agencies which oversee them.

Conclusion

The unexpected onset of the COVID-19 pandemic exposed many flaws in our economic system and made it clear just how vulnerable many Maine workers were. The arrival of the pandemic itself was unexpected, but much of the resulting fallout was not. Issues like a lack of worker power, poor wages, and a lack of access to paid leave were well-known for years. The difficulties employers face in staffing support were similarly predictable in industries that have long been notable for their low wages, poor benefit provision, and unpredictable scheduling practices. Larger structural barriers such as access to child care and racial and ethnic discrimination were no secret.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought these problems into starker relief than ever before. It is urgent for policymakers to address the needs of workers in Maine, both to recognize the hardships incurred by working Mainers over the past 18 months and to ensure a robust recovery to an economy that is stronger and more inclusive. This is especially true for those workers with low wages whose jobs were branded as “essential” during the pandemic, but whose working conditions were among the worst of any jobs.

Just as the most urgent problems for Maine workers were known before the pandemic, many of the solutions are also familiar and well-researched. Maine would not be in uncharted territory in implementing any of the policy recommendations in this report. Most have already been tried and tested in other states, and many are the norm in wealthy industrialized nations.

The time to act is now. There has never been a clearer case for empowering workers and improving the lives of hundreds of thousands of working Mainers. The urgency of the problem and the availability of proven solutions have combined in this moment, and lawmakers must seize the opportunity to rebuild an economy in a more sustainable and equitable manner.

Appendix

Endnotes

US Bureau of Economic Analysis, quarterly state gross domestic product estimates.

US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Local Area Unemployment Statistics data. April employment was approximately

86,000 below pre-pandemic levels.

Brauner, Jan M., et al., “Inferring the effectiveness of government interventions against COVID-19,” Science, vol. 371, issue 6531 (February 2021). https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abd9338

Famiglietti, Matthew & Fernando Leibovici, “COVID-19 Containment Measures, Health and the Economy,” St Louis

Federal Reserve. February 18, 2021. https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/first-quarter-2021/covid-19-containment-measures-health-economy

US Census Bureau, Current Population Survey monthly data, May-July 2021, three-month average via the

Integrated Public Use Microdata System (IPUMS). Over this period, 28 percent of Maine workers said they were

working remotely due to COVID-19.

Gould, Elsie & Valerie Wilson, “Black workers face two of the most lethal preexisting conditions for coronavirus—

racism and economic inequality,” Economic Policy Institute. June 1, 2020. https://www.epi.org/publication/blackworkers-covid/

Maine Centers for Disease Control data.

Do, D. Phuong & Frank Reanne, “Using Race- and Age-Specific COVID-19 case data to investigate the

determinants of the excess COVID-19 mortality burden among Hispanic Americans,” Demographic Research Vol 44,

Issue 29 (April 2021): pp. 699-718. https://www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol44/29/44-29.pdf

Mangundayao, Ihna, et al., “Worker protection agencies need more funding to enforce labor laws and protect

workers,” Economic Policy Institute. July 29, 2021. https://www.epi.org/blog/worker-protection-agencies-need-morefunding-to-enforce-labor-laws-and-protect-workers/

Meyer, Mal, “Over 70 Maine businesses notified for violating COVID-19 safety rules,” WGME. January 11, 2021.

https://wgme.com/news/local/over-70-maine-businesses-notified-for-violating-covid-19-safety-rules

Myall, James, “State of Working Maine, 2019,” Maine Center for Economic Policy. December 18, 2019. https://www.mecep.org/maines-economy/state-of-working-maine-2019/

Massachusetts Department of Public Health, “COVID-19 Community Impact Survey (CCIS): Preliminary Analysis

of Results as of October 13, 2021.” https://www.mass.gov/doc/covid-19-community-impact-survey-ccis-preliminaryanalysis-results-full-report/download, pages 113, 474

Pichler, Stefan & Nicholas R Ziebarth, “The pros and cons of sick pay schemes: testing for contagious

presenteeism and noncontagious absenteeism behavior,” Journal of Public Economics Vol 156 (December 2017):

pp. 14-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.07.003 and Pichler, Stefan et al., “Positive health externalities of

mandating paid sick leave,” IZA Institute of Labor Economics. July 2020. https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/13530/positive-health-externalities-of-mandating-paid-sick-leave

Pilcher, Stefan et, al, “COVID-19 Emergency Sick Leave Has Helped Flatten the Curve in the United States,”

Health Affairs. October 15, 2020 https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00863 and Schenider, Daniel

et al., “Olive Garden’s Expansion Of Paid Sick Leave During COVID-19 Reduced The Share Of Employees Working

While Sick,” Health Affairs. Aug 2021. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02320

Myall, James, “Coronavirus highlights the need for all workers to have paid sick leave,” Maine Center for Economic

Policy. March 3, 2020. https://www.mecep.org/blog/coronavirus-highlights-the-need-for-all-workers-to-have-paidsick-leave/

For an overview, see Brannon, Hugh & Elizabeth Campbell, “Forced Arbitration Helped Employers Who

Committed Wage Theft Pocket $40 Million Owed To Maine Workers In 2019,” National Employment Law Center.

May 20, 2021. https://www.nelp.org/publication/forced-arbitration-helped-employers-who-committed-wage-theftpocket-40-million-owed-to-maine-workers-in-2019/

O’Donnell, Jimmy, “Essential workers during COVID-19: At risk and lacking union representation,” Brookings

Institution. September 3, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/09/03/essential-workers-duringcovid-19-at-risk-and-lacking-union-representation/

Ferdosi, Mohammad, et al., “Assessing the Impact of COVID-19 on Ontario Workers, Workplaces and Families,”

McMaster University School of Labor Studies. Accessed October 19, 2021. https://www.whsc.on.ca/What-s-new/NewsArchive/Unions-an-important-support-for-workers-during-COVID-study-finds

Moore, Sian, et al., “Research into Covid-19 workplace safety outcomes in the food and drinks sector,” Trade

Unions Council. March 2021. https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/research-covid-19-workplace-safetyoutcomes-food-and-drinks-sector

US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Local Area Unemployment Statistics data.

Alegretto, Sylvia & Stephen Potts, ” The Great Recession, Jobless Recoveries and Black Workers,” Joint Center for

Political and Economic Studies. Accessed October 19, 2021. https://irle.berkeley.edu/files/2010/The-Great-RecessionJobless-Recoveries-and-Black-Workers.pdf

US Census Bureau, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020. September 14, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-273.html

Ibid.

MECEP analysis of Maine Department of Labor, Unemployment Insurance claims data; US Census Bureau, CPS

monthly data via IPUMS.

MECEP analysis of US Census Bureau, Household Pulse data, phase 3.1, weeks 28-33 pooled data.

Ibid.

US Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2019 one-year data via data.census.gov. Tables S1601,

B16005H. Of white, non-Hispanic Mainers over the age of 5, 3.9 percent speak a language other than English at

home. The same is true of 33 percent of Mainers of color.

Hubbard, Glenn & Michael R. Strain, “Has the Paycheck Protection Program Succeeded?” Brookings Institution.

September 23, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/bpea-articles/has-the-paycheck-protection-program-succeeded/

US Small Business Administration, Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Report: Approvals Through 8/8/2020.

https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/2021-09/PPP_Report%20-%202020-08-10-508.pdf

“More Than 2,400 Maine Small Employers Were Approved for $221 Million in Forgivable Loans in the First Two

Weeks of PPP’s Reopening,” Office of US Senator Susan Collins. January 29, 2021. https://www.collins.senate.gov/newsroom/more-2400-maine-small-employers-were-approved-221-million-forgivable-loans-first-two-weeks

MECEP analysis of CPS data via IPUMS, May-August 2020.

Chetty, Raj, et al., “The Economic Impacts of COVID-19: Evidence from a New Public Database Built Using Private Sector Data,” Opportunity Insights Tracker. November 2020. https://opportunityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/tracker_paper.pdf

; Autor, David, et al., “An Evaluation of the Paycheck Protection Program Using

Administrative Payroll Microdata,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology. July 22, 2020. https://economics.mit.edu/files/20094; and Granja, João et al., “Did The Paycheck Protection Program Hit The Target?,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 27095. September 2021. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27095/w27095.pdf

Atkins, Rachel et al., “Discrimination in lending? Evidence from the Paycheck Protection Program,” Social

Scholars Strategy Network. June 22, 2021. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3774992

“Lending Discrimination During COVID-19: Black and Hispanic Women-Owned Businesses.” National Community

Reinvestment Coalition. Accessed October 19, 2021. https://ncrc.org/lending-discrimination-during-covid-19-blackand-hispanic-women-owned-businesses/

US Small Business Administration, Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Report: Approvals Through 8/8/2020.

https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/2021-09/PPP_Report%20-%202020-08-10-508.pdf

MECEP analysis of US Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, weeks 1 through 27.

US Census Bureau, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020. September 14, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-273.html

MECEP analysis of US Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, weeks 13 through 27. On average over this

period, 28 percent of adults said they lived in a household which found it “somewhat” or “very” difficult to “meet

their usual household expenses” in the reference week.

See, for example, Carson, Juliana, et al., “Universal School Meals and Associations with Student Participation,

Attendance, Academic Performance, Diet Quality, Food Security, and Body Mass Index: A Systematic Review,”

Nutrients, Vol 13, issue 3 (March 2021): p911. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33799780/

The non-elderly adult uninsured rate in 2019 was 11.6%, according to the US Census Bureau, American

Community Survey. The Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey found that, among the same population, 9.7% were uninsured in May and June 2020 (weeks 1-8), and 8.0% in May and June 2021 (weeks 29-32).

Karpman, Michael & Stephanie Zuckerman, “The Uninsurance Rate Held Steady during the Pandemic as Public

Coverage Increased,” Urban Institute. August 2021. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104691/uninsurance-rate-held-steady-during-the-pandemic-as-public-coverage-increased_final-v3.pdf

“Child Care Gaps in 2019: Maine,” Bipartisan Policy Center. Accessed October 19, 2021. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/download/?file=/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Maine.pdf

Health Management Associates, 2021 Maine Child Care Market Rate Survey. May 27, 2021. https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/sites/maine.gov.dhhs/files/inline-files/2021%20Market%20Rate%20Survey_Final.pdf

“The Cost of Child Care in Maine,” Economic Policy Institute. Updated October 2020. https://www.epi.org/childcare-costs-in-the-united-states/#/ME

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment Statistics, May 2020.

Maine Department of Health and Human Services, “Child Care Plan for Maine: May 2021,” p3. https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/sites/maine.gov.dhhs/files/inline-files/FINAL%20Child%20Care%20Plan%20for%20Maine.pdf

Health Management Associates, 2021 Maine Child Care Market Rate Survey. May 27, 2021, p14. https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/sites/maine.gov.dhhs/files/inline-files/2021%20Market%20Rate%20Survey_Final.pdf

MECEP analysis of US Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey.

Maine Department of Health and Human Services, “Child Care Plan for Maine: May 2021.” https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/sites/maine.gov.dhhs/files/inline-files/FINAL%20Child%20Care%20Plan%20for%20Maine.pdf

Myall, James, “State of Working Maine 2020,” Maine Center for Economic Policy. November 9, 2021. https://www.mecep.org/maines-economy/report-state-of-working-maine-2020/

Dube, Arindrajit, “Aggregate Employment Effects of Unemployment Benefits During Deep Downturns: Evidence

from the Expiration of the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation,” National Bureau of Economic Research.

Working Paper 28470. February 2021. https://www.nber.org/papers/w28470

Hickey, Sebastian M., and David Cooper, “Cutting unemployment insurance benefits did not boost job growth,”

Economic Policy Institute. August 24, 2021. https://www.epi.org/blog/cutting-unemployment-insurance-benefits-didnot-boost-job-growth-july-state-jobs-data-show-a-widespread-recovery/

Maine taxable sales data. Restaurant sales in June 2021 were up 8 percent compared to June 2019; lodging

sales were up 27 percent.

MECEP analysis of Maine Revenue Services, monthly taxable sales data.

Parker, Kim et al., “Unemployed Americans are feeling the emotional strain of job loss; most have considered

changing occupations,” Pew Research Center. February 10, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/02/10/unemployed-americans-are-feeling-the-emotional-strain-of-job-loss-most-have-considered-changing-occupations/

Maine Department of Labor, “Barriers to employment: Key findings from recent survey effort.” Accessed

October 19, 2021. https://www.maine.gov/labor/docs/2021/Barrierstoemployment_Findings%20and%20Analysis_091321.pdf

MECEP calculation using methodology developed by the Economic Policy Institute. For details, see https://www.epi.org/publication/raising-the-federal-minimum-wage-to-15-by-2025-would-lift-the-pay-of-32-million-workers/. High risk industries are those defined in Figure 3. It excludes workers in Portland and Rockland, where local ordinances

will already raise the local minimum wage to $15 per hour, and includes a number of agricultural workers who are

currently not subject to Maine’s minimum wage law.

National Women’s Law Center, “Tipped Workers by State.” September 2019. https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Women-Tipped-Workers-State-by-State-2019-v2.pdf

Bui et al., ”Racial and Ethnic Disparities Among COVID-19 Cases in Workplace Outbreaks by Industry Sector –

Utah, March 6, June 5, 2020” US Centers for Disease Control, Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report 2020; issue 69 pp.

1133-1138. http://dx.doí.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6933e3

Chen, Yea-Hung, et al., “Excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic among Californians 18–65 years of age, by occupational sector and occupation: March through October 2020,” PLOS One. June 4, 2021. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.01.21.21250266v1.full

Contreras, Zulema et al., ”Industry Sectors Highly Affected by Worksite Outbreaks of Coronavirus Disease, Los Angeles County, California, USA, March 19-September 30, 2020.” Emerging Infectious Diseases, Vol 27, issue 7 (July

2021): pp. 1769-1775. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2707.210425

Hawkins, Devean, et al., “COVID-19 deaths by occupation, Massachusetts, March 1-July 31, 2020,” American

Journal of Internal Medicine, Vol 64, issue 4 (Apr 2021): pp. 238-244. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8013546/

Wuellner, Sara, “Washington COVID-19 Cases by Industry, January 2020-June 2020,” Washington

State Department of Labor and Industries. January 2021. https://lni.wa.gov/safety-health/safety-research/files/2021/103_06_2021_COVID_Industry_Report.pdf

“Fact Sheet: The Pandemic’s Toll on California Workers in High Risk Industries” University of California MERCED.

April 2021. https://clc.ucmerced.edu/sites/clc.ucmerced.edu/files/page/documents/fact_sheet_-_the_pandemics_toll_on_california_workers_in_high_risk_industries.pdf

Song, Hummy, et al., “The Impact Of The Non-Essential Business Closure Policy On Covid-19 Infection Rates,”

National Bureau of Economic Research, working paper 28374. January 2021. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28374/w28374.pdf