Carnival, Crop Over and the West Indian Day Parades of the Caribbean Diaspora have always been sites of release and exuberance. This year, with so many celebrations cancelled or delayed and so many unable to travel and join in, Caribbean and Caribbean American writers reflect on the many meanings and experiences of Carnival.

“You moving to VI North!” This is what my uncle said to me when I announced that I was moving to Atlanta. It’s what everyone was saying to me.

“Eat at St. Thomas Bakery in Stone Mountain.”

“I’ll be there for a wedding in Buckhead.”

“Look up Teresa, she running things over in Decatur.”

Virgin Islands North. That was Atlanta. When I first moved, I saw a pair of toy boxing gloves stamped with the VI flag hanging from someone’s rearview mirror and I screamed at the driver, waving manically. I did this maybe five times the first few days until I realized that I was seeing VI flags in parking lots, on the highway, in the windows of people’s homes, on people’s clothes, and tattooed on people’s arms.

There was the handyman I found on an app who came to put together my kids’ beds when we moved in. He recognized my grandmother in a picture. “My librarian!” he said smiling.

There was the woman at the car rental who spoke like a Georgian, who then switched it up and spoke St. Thomian when she realized we were from the same neighborhood. And on and on. The most common thing Virgin Islanders said to me? “I’ll be there for Atlanta Carnival. Going make a real scene.”

All of this is why I moved to Atlanta. True, I had a great new job. But I had a good job before too. In Atlanta, I now had tons of cousins and aunties and uncles. And most importantly, my children had cousins and aunties and uncles. The kids had access to Virgin Islands culture, which I imagined would mean that we would easily make new friends and new family. I hoped for this for my children, because their father and I had recently divorced. I wanted to give the children, and myself, at least one positive outcome from the most awful thing that had ever happened to them.

I was born and raised in the Virgin Islands. I’d had examples of Black excellence my whole life, and also Black failure. And Black beauty and Black ugly … and well, all of humanity in Blackness. Racism surely existed in the Virgin Islands, but I didn’t really know racism as a thing until I came to the States. My freshman year of college, I came back from partying at MIT’s Chocolate City one night to find my white roommate still up studying for the Intro to Psych class we were both in. “How are you on the Dean’s List just like me?” she asked in tears. “I’m not here because of affirmative action! But you are the one out dancing every night!”

Which is to say that firstly, Black people are fully complex humans, and so I knew all of that could be in me. And secondly, white people, it seemed, thought that dancing every night meant that I wasn’t smart or hardworking.

When I decided where my children and I would live post-divorce, I knew I wanted them to grow up in a Black city. I wanted them to grow up in a place with Virgin Islanders, because that seemed like the surest way to get them to see Black people themselves as fully nuanced human beings. Check, check, Atlanta. With Blackness and Caribbeanness would come Carnival. And with Carnival would come dancing.

My youngest boy would play steelpan, as I did growing up. My eldest boy decided on moko jumbie, following his favorite cousin back home. My daughter became a majorette, as one of my aunt’s had been. Her troupe—the Virgin Islands Majorettes of Atlanta—was one I had actually seen in a Carnival parade when I lived in St. Thomas. The year 2020 was going to be tremendous for my kids, because not only would they all perform in Atlanta’s Caribbean Carnival, but their various groups were also going home to be in the St. Thomas Carnival. It would be my children’s first Carnival, and it would be in their new home of Atlanta, and in their ancestral home of the Virgin Islands.

Here is something to know about being in any Caribbean Carnival. You play music, twirl a baton, march on stilts, all while looking fabulous. You wear frills and tulle and glitter and pleats and probably a sparkling headpiece. You smile and laugh and, most of all, you dance. You, almost by definition of it being a Carnival parade, make a scene. And you do so gleefully.

When COVID-19 canceled Carnival in Atlanta, and then in the Virgin Islands, my children lost part of their social network, they lost much of the new skills they had learned, and they lost a sense of doing something meaningful—something that made them feel special. Feeling special has always had a confidence-boosting effect on people, especially kids.

But there was something else. Something more slippery, which I wouldn’t have been able to put into words, despite being a writer, until my own children started asking questions about Black people being killed by the very people hired to protect all people. See, it ended up being that the first time my children took to the street in Atlanta was not for Carnival, where their bodies would be beautiful, tall, strong, agile, musical, full of life. Instead, my children’s first time in a crowded Atlanta street was for a march, a protest asking as its primary request that Black lives just please matter enough so they don’t get unmade so easily.

When a child is dancing in the street—I mean shaking ass and hips, and dancing and being loud and messy; when that child is doing a baton twirl that most people in the world can’t even begin to figure out how to do; or making music on instruments that most people in the world don’t even understand can make music at all; or walking around on tall stills, taller than any possible human—that child knows themself to be special. They know it so sincerely that they are taking it completely for granted. Because they are dancing, remember, in the very streets, in broad day light. If this child is a Virgin Islander, they may be playing the same instrument their mother played, walking on stilts their cousin walked on, or twirling the baton their auntie twirled. Every single person around them is affirming that these children are special. Because at a Caribbean Carnival, everyone is dancing. The bystanders are bydancers. For a child in a Caribbean Carnival, Black life mattering is so low a bar it is to be completely unconsidered.

So 2020 Carnival would have been my children’s first opportunity to know their bodies as so safe that they can dance wildly in the public street. In much of the States, we call that “dancing like no one is watching,” because for many white and straight Americans, true safety is attained in solitude, behind the protection of walls. But for Caribbean-Americans who know Carnivals around the country, New Orleanians who know Mardi Gras, Black Americans who know homecomings around the South, and queer Americans who know Pride, safety has always come in being watched over, in being seen and celebrated.

This is what was taken from my children when Carnival was canceled. The quarantining of COVID-19 took not just the safety of my children’s health; it took an opportunity of existential safety, which is the first safety. The first safety you know is the one when you come hollering out of your mother’s womb, and all the people gathered there to watch you naked and messy and loud make clear that your shouting isn’t scary; your shouting isn’t a reason to kill you, but instead, your naked messy hollering is a signal that you are alive.

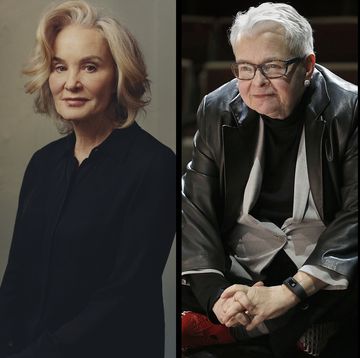

Tiphanie Yanique is from Saint Thomas, Virgin Islands. She is the author of the novel Land of Love and Drowning and the story collection How to Escape from a Leper Colony. She teaches at the Emory University and lives in Atlanta, GA.