Health matters: rough sleeping

Updated 11 February 2020

Summary

This edition of Health Matters focuses on the scale of rough sleeping in England, the causes and consequences of rough sleeping (including the links with poor physical and mental health, prevention and effective interventions) and relevant calls to action.

Ill-health can be both a cause and consequence of homelessness, although it is not always identified as the trigger of homelessness. For example, ill-health may contribute to job loss or relationship breakdown, which in turn can result in homelessness.

Homelessness can be seen as a measure of our collective success in reducing health inequalities, with rough sleeping the most extreme and damaging to health. Reducing homelessness will contribute to a reduction in health inequalities and improvements in a wide range of health outcomes.

The government’s Rough Sleeping Strategy, published in 2018, commits to halving rough sleeping by 2022 and ending it by 2027. The strategy states that achieving this ambition will require central and local government to work collaboratively and innovatively with business, communities, faith and voluntary groups and the general public.

Cross-government working is essential in preventing and relieving rough sleeping, as well as ensuring that ill health is not a cause of or barrier to, people moving away from rough sleeping. At a local level, this involves collaboration between the NHS, local authorities, social care and housing services.

Rough sleeping and its causes

Homelessness and rough sleeping

The definition of homelessness is not having a home.

You are experiencing homelessness if you have nowhere to stay and are living on the streets, but you can experience homelessness even if you have a roof over your head. Homelessness does not just refer to people who are experiencing rough sleeping.

The following housing circumstances are examples of homelessness:

- people without a shelter of any kind, sleeping rough

- people living in hostels, shelters, refuges or other temporary circumstances, for example in institutions

- people staying temporarily with family and friends (‘sofa surfing’) and people who are threatened with eviction

- people living in unfit housing or extreme overcrowding

For the purposes of conducting rough sleeping street counts and evidence based estimates, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) defines people who sleep rough as:

-

People sleeping, about to bed down (sitting on/in or standing next to their bedding) or actually bedded down in the open air (such as on the street, in tents, doorways, parks, bus shelters or encampments).

-

People in buildings or other places not designed for habitation (such as stairwells, barns, sheds, car parks, cars, derelict boats, stations, or “bashes” which are makeshift shelters often comprised of cardboard boxes).

The definition does not include:

- people in hostels or shelters

- people in campsites or other sites used for recreational purposes or organised protest

- squatters

- travellers

This definition is used for the purpose of rough sleeping estimates. However, policy, programmes and services currently being developed, designed and delivered recognise that people move in and out of periods of rough sleeping. Rough sleeping can be a transitory state, and many experience a ‘revolving door’ cycle, moving in and out of short-term accommodation.

This edition of Health Matters will focus specifically on people experiencing rough sleeping, including those who may move in and out of short-term accommodation, who experience some of the most extreme health inequalities.

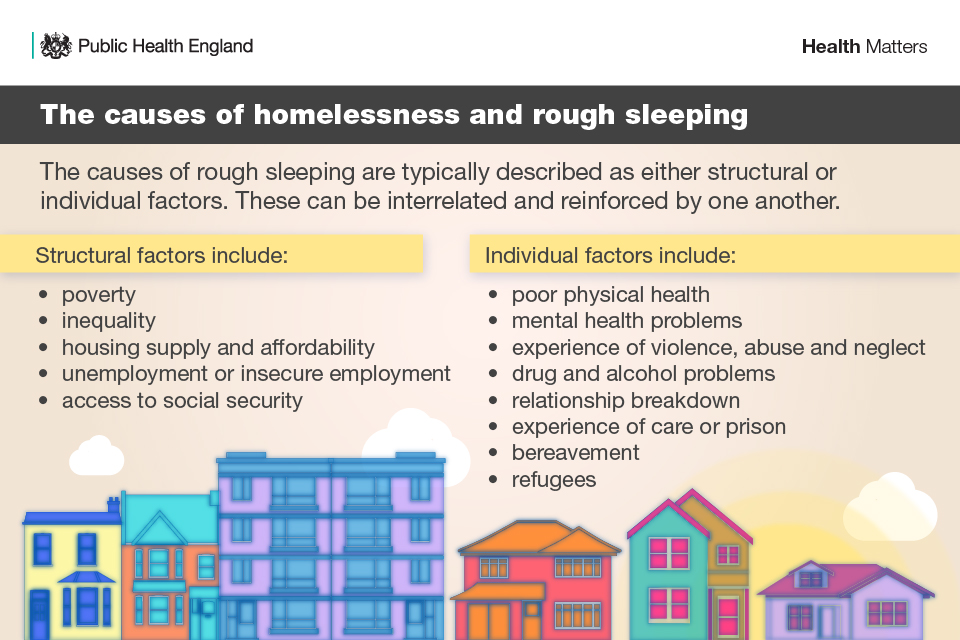

The causes of homelessness and rough sleeping

The causes of rough sleeping are typically described as either structural or individual. Structural explanations locate the causes of homelessness in broader forces, and individualist explanations focus on the personal vulnerabilities and circumstances of those who experience rough sleeping.

Homelessness is often the consequence of a combination and culmination of these factors, which can be interrelated and reinforced by one another. Causes and relationships between these factors vary across the life course.

What the statistics tell us

Rough sleeping across England

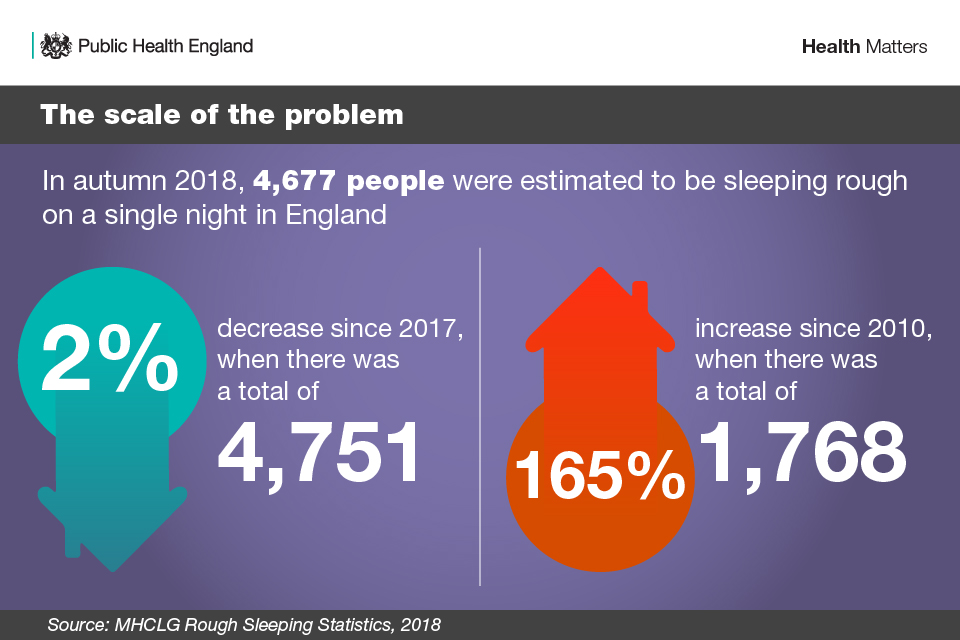

Official estimated numbers of people who experience rough sleeping have increased by 165% since 2010 to 4,677.

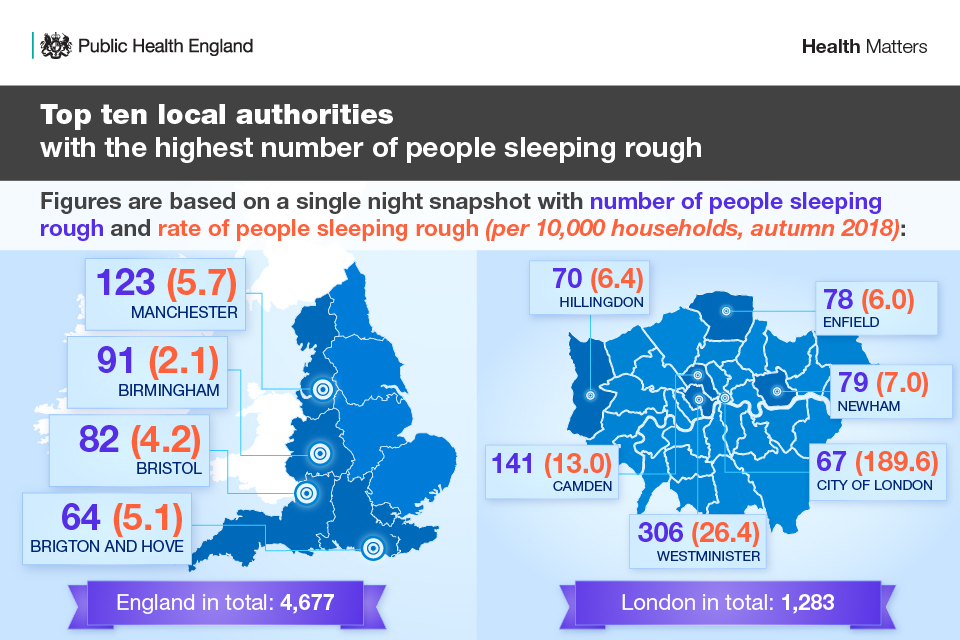

Rough sleeping is unevenly distributed across the country, with trends showing that it has increased in many different areas. The largest increases since 2010 have been in urban areas, with rural areas and some seaside towns seeing smaller increases.

Our knowledge of who sleeps rough and why is imperfect. Accurately measuring the exact numbers of people who experience rough sleeping is challenging as there are many practical difficulties, particularly giving the hidden nature of rough sleeping. One primary difficulty is covering the entire area of a local authority in a single evening.

Research from Crisis estimates that more than 8,000 people were sleeping rough across England in 2016. This is predicted to rise to 15,000 by 2026, if nothing changes.

There are also various factors that affect the number of people sleeping rough on any given night, including:

- weather

- availability of night shelters and other alternatives

- where people choose to sleep

- the date and time chosen for the count

Local authorities decide whether to carry out a street count of visible rough sleeping, an evidence-based estimate, or an estimate informed by a spotlight street count, based on what is most appropriate in their area. The aim is to get as accurate a representation of the number of people sleeping rough as possible.

Further information on data limitations is outlined in the MHCLG report on rough sleeping statistics in Autumn 2018.

MHCLG’s impact evaluation of the Rough Sleeping Initiative specifically looked at whether areas changing their approach for measuring rough sleeping had any impact, as well as a range of other factors, including previous levels of homelessness and rough sleeping, local housing provision, labour market conditions and the weather.

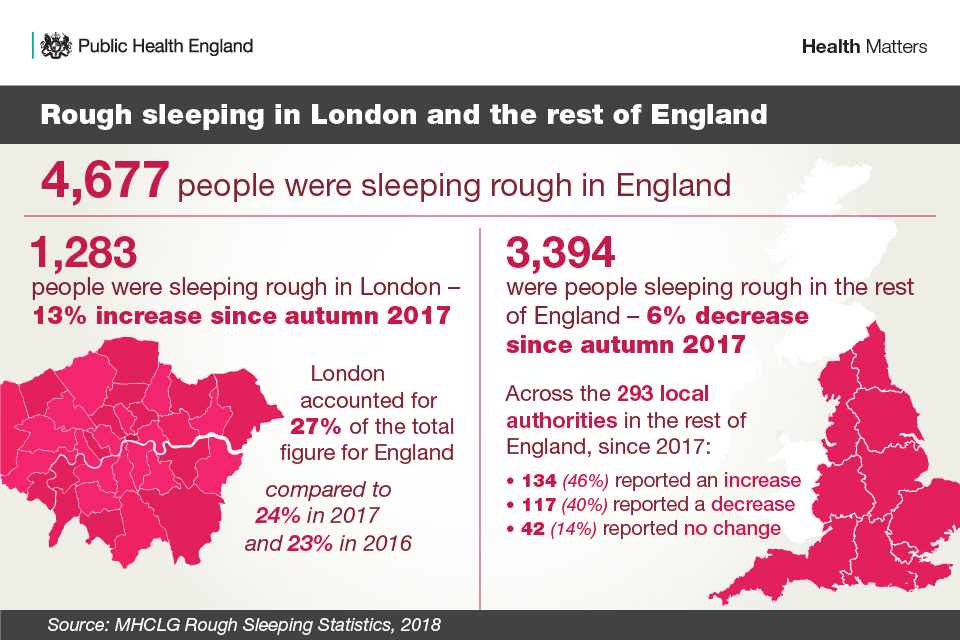

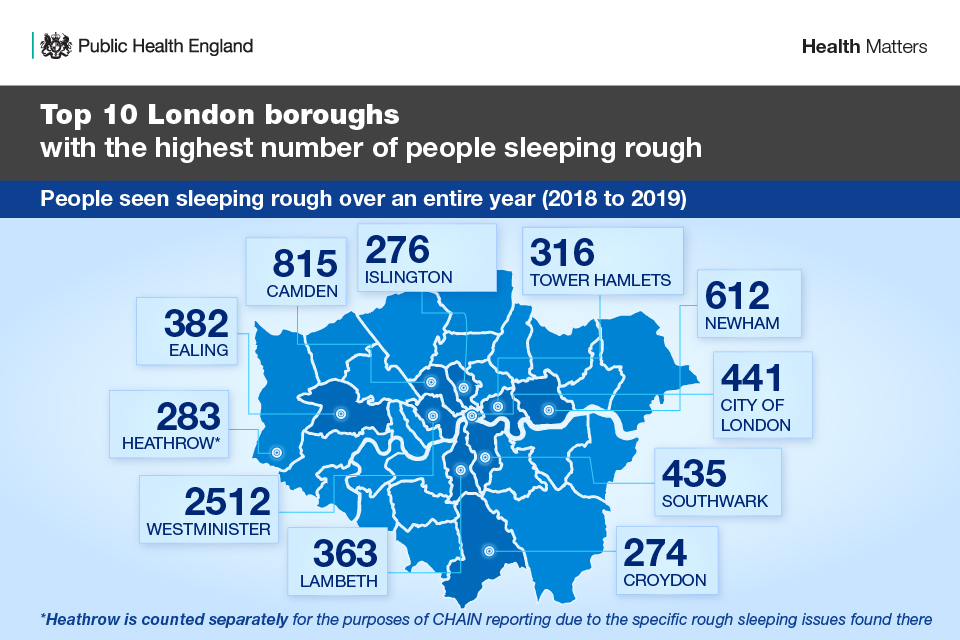

The data for London, in the infographic below, is based on Combined Homelessness and Information Network (CHAIN) data which differs fundamentally from national street count statistics. Information recorded on CHAIN constitutes an ongoing record of all work done year-round by outreach teams in London, covering every single shift they carry out. In this sense, it is much more comprehensive than street count data which represents a snapshot of people seen rough sleeping on a single night.

However, street count data tends to be referenced more regularly when analysing nationwide trends, as most other areas of the UK do not operate equivalent systems to CHAIN for recording their general work.

The demographics of people who experience rough sleeping

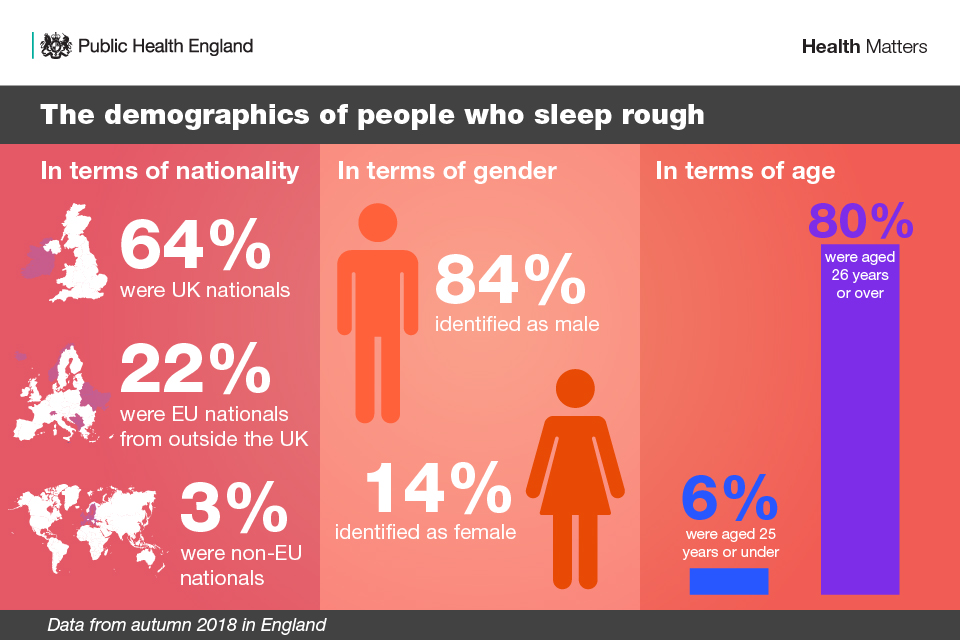

In the 2018 counts and estimates, 84% of people experiencing rough sleeping were men, while 14% were women (gender for the remaining 2% was unknown). 80% were aged over 25 years. 64% were UK nationals, 22% EU nationals and 3% non-EU nationals.

Research suggests that there has been an upward trend of women sleeping rough, in both proportional and absolute terms. The average age of death for women who experience rough sleeping is lower than that of men who sleep rough.

There is increasing evidence showing that the cause of women’s homelessness, and trajectories they take through it, tend to differ from those of homeless men, and, for multiple reasons, women who experience rough sleeping also experience increased vulnerability.

Evidence has shown that women who experience rough sleeping also experience higher rates of mental ill-health. These women are also more likely to experience sustained or repeated rough sleeping.

Women who experience rough sleeping are more likely than men to have experienced traumas, including self-harming and domestic violence. Despite not always being a direct cause of homelessness, evidence has shown that experience of domestic violence and abuse is very common among women who become homeless.

Women who sleep rough also tend to make themselves less visible in order to stay safe, by moving at night or concealing themselves or their gender. As a result, information about them and their needs is less well known than for men.

The impact of rough sleeping on age of death

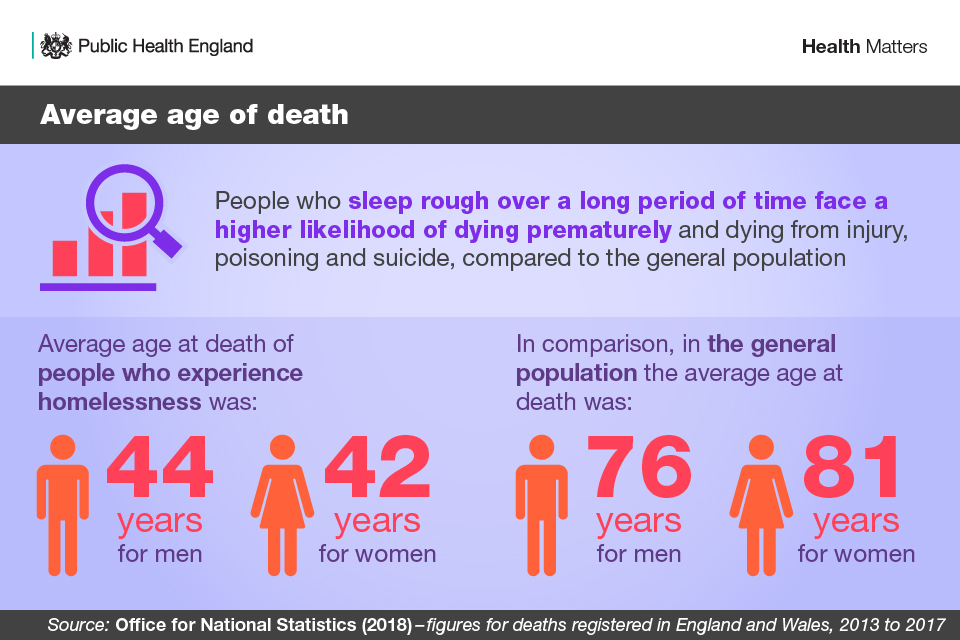

People who experience rough sleeping over a long period are, on average, more likely to die young than the general population.

They also face a higher likelihood of dying from injury, poisoning and suicide. It has been estimated that around 35% of people who die whilst sleeping rough die due to alcohol or drugs, compared to 2% in the general population.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) recently published the first Experimental Statistics of the number of deaths of homeless people in England and Wales, predominantly based on the records of people, at or around time of death, experiencing rough sleeping or using emergency accommodation such as homeless shelters and direct access hostels.

These statistics reported that in 2017, there were an estimated 597 deaths of homeless people in England and Wales, a figure that has increased by 24% over the last 5 years. Men made up 84% of these deaths.

In 2017, over half of all deaths of homeless people were due to 3 factors:

- accidents, including drug poisoning, accounted for 40%

- suicides accounted for 13%

- diseases of the liver accounted for 9%

A University College London study found that a third of deaths among people experiencing homelessness were due to conditions such as tuberculosis and gastric ulcers which are amendable to timely and effective health care.

The study also compared deaths in homeless people to those of a similar group of people, in terms of age and sex, in the lowest socioeconomic category but who had a home, and found that:

- those in the homeless group were twice as likely to die of strokes as the poorest people who had stable accommodation

- those in the homeless group were more substantially affected by cardiovascular disease as a whole

- a fifth of the 600 deaths were caused by cancer

- another fifth died from digestive diseases such as intestinal obstruction or pancreatitis

The physical and mental health needs of people who experience rough sleeping

People who sleep rough experience some of the most severe health inequalities and report much poorer health than the general population. Many have co-occurring mental ill health and substance misuse needs, physical health needs, and have experienced significant trauma in their lives.

Physical health needs

The poorer health outcomes that homeless people experience compared to the general population are related to:

- exposure to poor living conditions

- difficulty in maintaining personal hygiene

- poor diet

- high levels of stress

- drug and alcohol dependence

Access to primary care is a major issue. Many people who are sleeping rough report being unable to register with a GP practice because they have no fixed address. NHS guidelines state that homeless people have a right to register and use all the services in a GP practice and that person does not need a fixed address or identification. Also the person’s immigration status does not affect registration.

Read this case study about a programme informing GP surgeries about the rights of homeless people to register for primary care.

NHS England has produced a leaflet that people who are homeless can use when they need to register with a GP.

Of the people seen sleeping rough in London in 2017 to 2018, 46% had physical health needs.

Available comparable data shows that almost all long-term physical ill-health needs are more prevalent in the homeless population than in the general population.

The prevalence of infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, HIV and hepatitis C, is significantly higher in the rough sleeping population than in the general population. Other health conditions with an increased risk include musculoskeletal disorders and chronic pain, skin and foot problems, dental problems and respiratory illness.

Read this case study on a new approach to engaging the rough sleeping and homeless community to attend tuberculosis screening sessions.

Access to health care for this population is different to that of the general population, with one-third of people who experience rough sleeping not being registered with a GP. Those who are registered may choose not to access the service.

St Mungo’s Homeless Charity looked at the records of people who were homeless, including those sleeping rough, who had used specialist homeless health care services. This research found that the average number of health visits was over 50 in 12 months.

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) found that people who are homeless are 3.2 times more likely to have an inpatient admission to hospital than the general population. Furthermore, attendance at accident and emergency is at least 8 times higher in the rough sleeping population than the housed population, and people who experience both homelessness and alcohol dependency were found to be 28 times more likely to have emergency admissions to hospital.

Read this case study on an approach to reduce A&E attendances and admissions to hospital by people who are experiencing homelessness.

Mental health needs

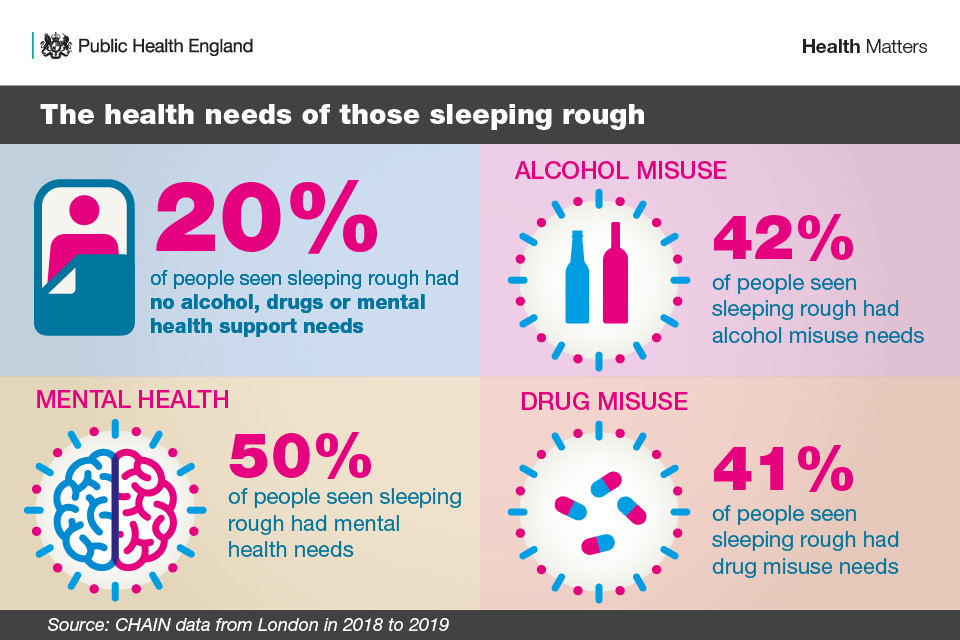

Evidence has shown that, compared with the general population, common mental health conditions (such as depression, anxiety and panic disorder) are over twice as high among people who experience homelessness, and psychosis is up to 15 times as high. Of the people seen sleeping rough in London in 2017 to 2018, 50% reported mental health needs.

Deaths of people experiencing both mental ill-health and rough sleeping have risen sharply since 2010. In 2017, 4 out of 5 (80%) of people experiencing rough sleeping who died in London had mental health needs, compared with 3 in 10 (29%) in 2010. Data from London CHAIN suggests that people sleeping rough with a mental health need are more likely to die than those without a mental health need.

The importance of safe, secure and affordable housing is well evidenced for people who experience mental ill-health.

There are correlations between mental health and a range of housing issues, for example:

- stress, anxiety, depression and other mental health needs

- poor housing conditions and-or housing insecurity

- overcrowding and mental ill-health, particularly for children and young people

- financial problems and mental ill-health

- self-medication with alcohol and drugs

According to CHAIN data, of those experiencing rough sleeping with mental health needs, the 3 most common reasons for loss of their last settled base were:

- eviction (20%)

- being asked to leave (18%)

- relationship breakdown (13%)

Evidence suggests that a significant number of people experiencing both rough sleeping and mental ill-health, do so after leaving an institution or housing where they accessed treatment, care or support.

For example, people experienced rough sleeping directly after:

- leaving an institution or housing such as hostels, prisons, hospitals and temporary accommodation

- discharge from mental health hospitals

Evidence suggests that mental ill-health can make moving off the streets and into accommodation more challenging. Research has shown that people are around 50% more likely to have spent over a year sleeping rough if they are also experiencing mental ill-health (compared to those who do not have mental health needs).

This may be, in part, due to services not being set up adequately to support people who experience rough sleeping or stringent inclusion criteria that may exclude this population from gaining access to services. This may also be due to mental ill-health acting as a barrier to engaging with housing services. For example, people with psychosis, delusional disorders and paranoia may experience mistrust towards street outreach workers and other professionals.

Evidence has shown that people who experience homelessness are also disproportionately affected by loneliness and can have limited contact with those who matter to them. Many people experiencing homelessness reported feeling isolated and like second-class citizens. This can undermine their attempts to seek help and move on from homelessness.

The NHS Long Term Plan sets out plans to invest up to £30 million on meeting the needs of people who experience rough sleeping, to ensure that the parts of England most affected by rough sleeping will have better access to specialist homelessness NHS mental health support, integrated with existing outreach services.

Drug and alcohol dependence

Substance dependence can be both a cause and consequence of homelessness. Those who are dependent on drugs or alcohol may struggle to retain accommodation due to financial difficulties, problems with behaviour or family relationship breakdown. Homelessness can also be the route to substance dependence.

In terms of substance dependence, homelessness and rough sleeping can affect:

- decisions to use for the first time, or continue to use, drugs and alcohol

- increased likelihood of relapse and overdose

- increased risk of transmission of blood-borne viruses, especially when injecting drugs

- increased risk of a range of other health conditions, including respiratory conditions and other comorbidities

- access to treatment and willingness to engage with it

- the ease with which treatment providers can continue to engage with their client

- the level of support available from family

National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS) statistics for 2017 to 2018 reported that 20% of people in drug and alcohol treatment have a housing problem to the extent that they are either rough sleeping or at serious risk of homelessness. This is higher for people in treatment for opiates (31%) and even higher for people in treatment for both opiates and new psychoactive substances (59%).

The 2018 to 2019 CHAIN data for London reports that of the people seen sleeping rough, 42% and 41% had alcohol misuse and drug misuse support needs respectively. Thirty-six percent had co-occurring mental health and drug and/or alcohol misuse support needs.

Co-occurring mental ill health and substance dependence is common amongst people who sleep rough. People may use alcohol and drugs to self-medicate for their mental ill-health, and may also use substances to help with sleeping, pain management and cold temperatures.

There is evidence that people experiencing rough sleeping with co-occurring needs find it challenging to engage with and/or experience other barriers to accessing treatment services. It is not uncommon for mental health services to exclude people because of co-occurring alcohol or drug use, a particular problem for those diagnosed with serious mental illness, who may also be excluded from alcohol and drug services due to the severity of their mental illness.

People in drug and alcohol treatment who have mental ill-health and housing problems are also less likely to successfully complete treatment. The increased mortality amongst people who are homeless or sleeping rough with substance dependence issues is concerning. There has been a substantial increase in drug poisoning deaths of homeless people, from 125 (26% of the total) in 2013 to 190 (32% of the total) in 2017. This is an increase of 52% over 5 years. Deaths from alcohol-specific causes also increased, with these deaths accounting for 10% of the total number of deaths in homeless people in 2017.

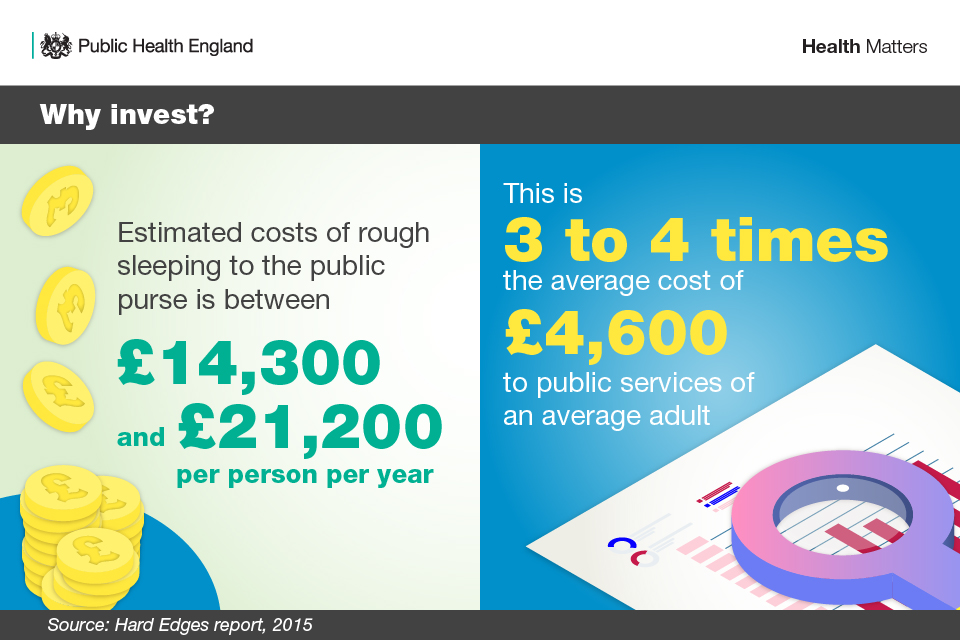

Investment

As well as the cost to the individual’s health, people experiencing rough sleeping generate a greater cost to the wider public purse than the general population. This includes costs of providing healthcare, emergency services, drug and alcohol treatment, and costs to the criminal justice system.

There are many reasons for this, not just that people experiencing rough sleeping can present with multiple and complex needs. They could have had previous experiences of public services that may not have been positive, affecting the way in which people choose to and are able to access to services.

Estimates of the costs of rough sleeping to the public purse can vary depending on the methodology and the data used. In the 2015 Hard Edges report, the costs of rough sleeping to the public purse were calculated to be between £14,300 and £21,200 per person per year. The higher cost being incurred if rough sleeping occurred alongside substance misuse and offending. This is 3 to 4 times the average cost to public services of an average adult (approximately £4,600).

The Rough Sleeping Advisory Panel, which is made up of leading experts from homelessness charities and local government, has highlighted the importance of health services in preventing rough sleeping and moving towards more collaborative working between housing, health care, public health and social care operations.

Call to action

The government’s Rough Sleeping Strategy states that: ‘Our vision is that by 2027 all parts of central and local government, in partnership with business, the public and wider society, are working together to ensure that no-one has to experience rough sleeping again’.

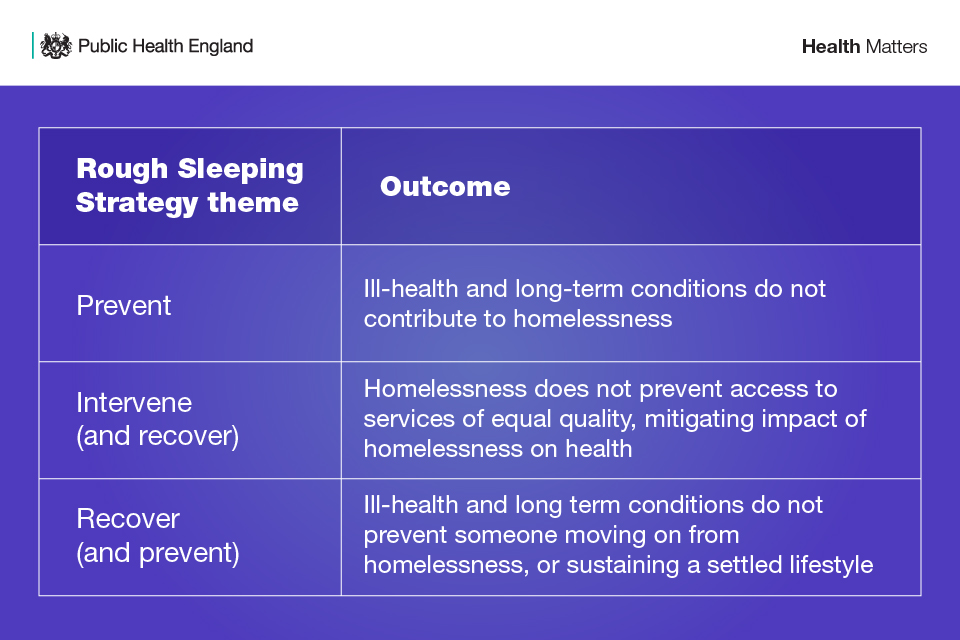

From a health perspective, the ambition is to improve health and wellbeing and reduce health inequalities through action to end rough sleeping. More specifically, we should be collectively seeking the following outcomes:

The recent Homelessness Reduction Act and Rough Sleeping Strategy, underpinned by the MHCLG’s Rough Sleeping Initiative, and actions taken by other government departments, Public Health England (PHE) and NHS England mark a significant shift in government’s response to rough sleeping.

The Homelessness Reduction Act marks a significant change in homelessness legislation in England. It places statutory duties on local housing authorities to intervene earlier with a package of advice and support to prevent homelessness.

The Act introduced a new ‘duty to refer’, from October 2018, requiring specified public authorities in England to notify local housing authorities of individuals they think may be homeless or threatened with becoming homeless in 56 days. This requires the person’s consent. The health services that the new duty applies to, are:

- accident and emergency services provided in a hospital

- urgent treatment centres

- hospital-based in-patient treatment services

In addition to the £30 million announced by NHS England in the Long Term Plan, The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) is funding PHE to run a grants scheme. This scheme, working with 6 areas across the country, will test and evaluate models that seek to improve access to health services for people experiencing rough sleeping who have co-occurring substance dependence and mental health needs. It is hoped that the evaluation of the 6 areas, due by Summer 2021, will add to the evidence base and inform policy.

At a local level, leaders in health and social care systems have an important role to play in improving health outcomes and reducing health inequalities amongst people who are experiencing rough sleeping.

PHE’s resource, Homelessness: applying All Our Health suggests actions that can be taken by front-line health and care professionals, service managers and local strategic leaders. Pivotal to this is the involvement of people with ‘lived experience’ of homelessness and rough sleeping in the design, commissioning and improvement of local services.

Commissioning and service provision should be informed by a local health needs audit, with homelessness and rough sleeping recognised by Health and Wellbeing Boards’ Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA), and if appropriate, Health and Wellbeing Strategies. Homeless Link have produced a briefing on including homelessness in local JSNAs.

The Faculty for Homeless and Inclusion Health’s Homeless and Inclusion Health Standards for Commissioners and Service Providers sets out clear minimum standards for planning, commissioning and providing health care for homeless people and other multiply excluded groups .

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) will be producing guidance on integrated health and care for people who experience rough sleeping, and later during financial year 2019 to 2020, PHE will be producing a toolkit on access to health services for people sleeping rough.

In 2018, MHCLG conducted a survey of access to health services in the 83 Rough Sleeping Initiative areas. The premise of the survey was that a health and care system that responds effectively to the needs of people sleeping rough should have the following components in place:

- An understanding of the needs of the rough sleeping population and the levels of health and social care provision.

- The inclusion of people with experience of rough sleeping and health and care services in the commissioning process.

- An understanding of whether these are currently available as specialist, targeted or mainstream services and the level of need for future commissioning.

- An understanding of sources of funding for the range of health services outlined above.

- An understanding of whether services are delivered to published standards, such as existing NICE guidance or the Faculty for Homeless and Inclusion Health Commissioning Standards.

- A clear understanding of which services are currently commissioned fully or partially with public funding that contribute to the specified outcomes for the population. These services should include:

- primary care services including access to GPs, community pharmacy and dental care

- mental health services including access to assertive outreach, community mental health teams, psychologist and talking therapies, crisis teams, hospital inpatient services, in-reach services and hospital discharge services

- allied health services including access to occupational therapists and podiatrists

- public health services including access to drug and alcohol treatment, tuberculosis treatment, immunisation, sexual health, diet and nutrition and smoking cessation service

- secondary care including urgent and emergency care, hospital discharge and in-reach services

- other services or settings including intermediate care, medical respite and palliative care

Ultimately, the call to action for all concerned to address the significant health inequalities experienced by people sleeping rough is the prevention and ending of homelessness.