“Are we celebrating anything this evening?” I love it when a server asks this question, because I get to answer, “Just life.” It’s jokey, but genuine. Who doesn’t feel fortunate to be seated in a nice restaurant, to share a special experience with friends or family, to be asked, “Gin or vodka?” when ordering a martini? Dining out is such a wonderfully easy way to feel alive.

But the more I dine, the more I realize it’s the lives of the folks behind the food and drink that we’re celebrating. We get asked often: What are you looking for in an Esquire Best New Restaurant? We’re always hooked when there is soul and a story to go with delicious, inventive dishes. It’s hard to deny the reflection of lived experience imbued in a menu, a wine list, a cocktail, atmosphere.

Over time, we’ve seen these stories—and the dynamic eateries they inspire—become even more deeply personal and eclectic. That’s especially true in this fortieth edition of our Best New Restaurants in America. To celebrate the milestone, this year we decided to rank the top forty new dining spots in the U. S. Finalizing our rankings required a healthy appetite. Four of us ate and drank our way across the country: Jeff Gordinier, Joshua David Stein, Omar Mamoon, and yours truly.

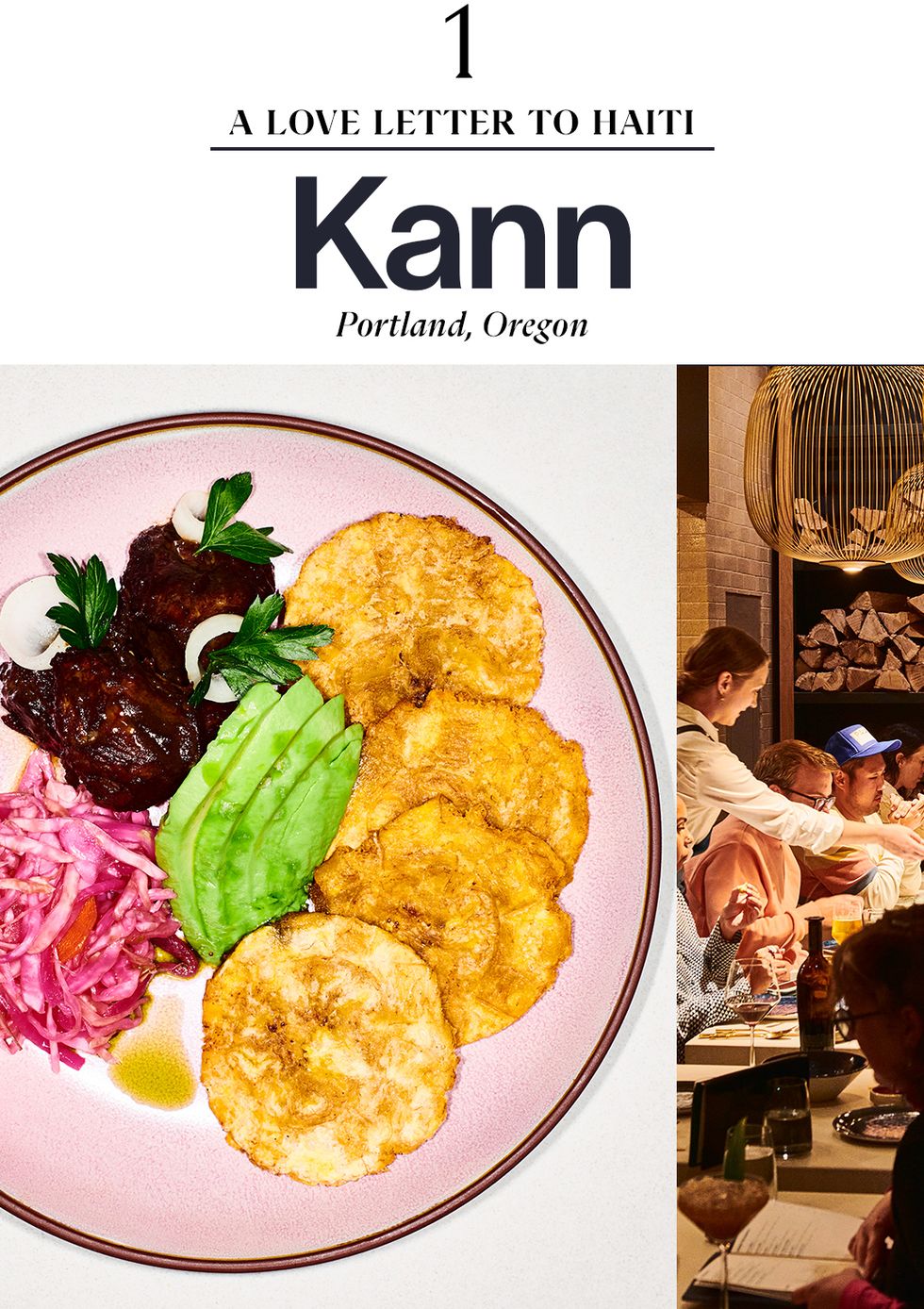

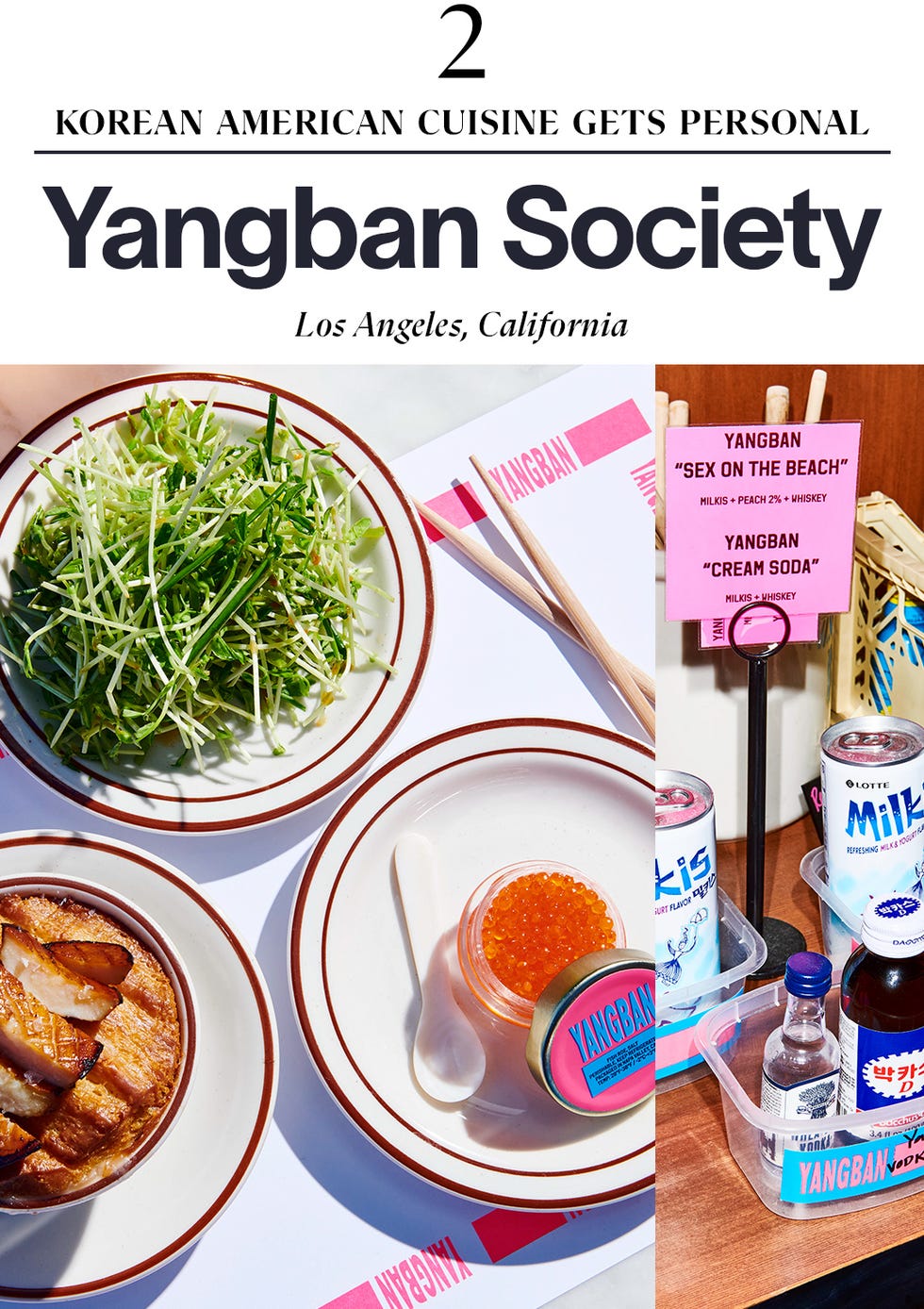

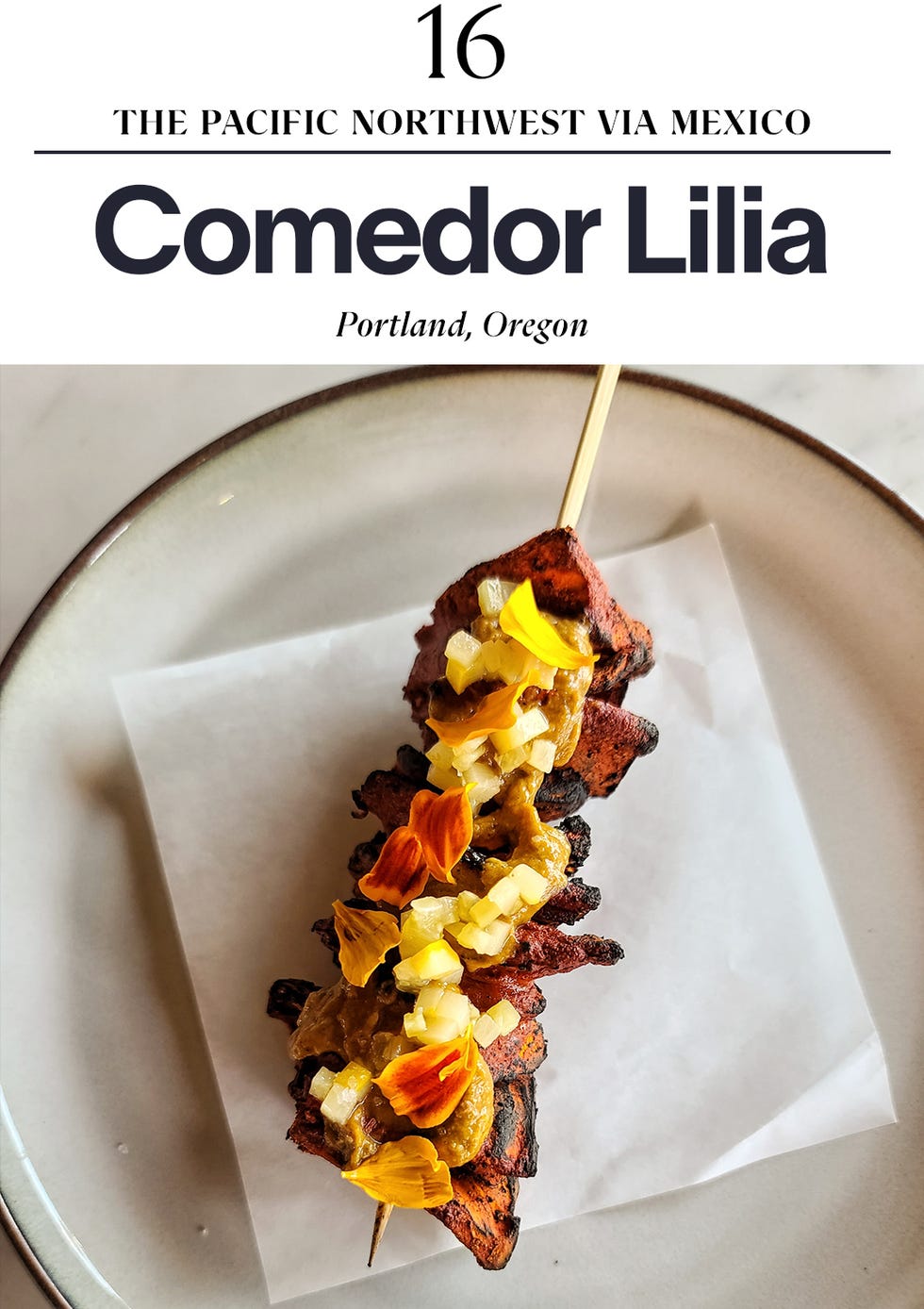

Along the way, we heard dozens of those inspiring origin stories. Over dessert at Kann one fall evening, chef Gregory Gourdet told me that he almost didn’t want to serve Haitian food in his first restaurant. Rather, he wanted to do something global. But when he cooked Haitian food on Top Chef and for Oprah and saw the impact it had on Haitians and Haitian Americans, he knew what he had to do. A similar spirit of mission inspires Katianna Hong at L. A.’s Yangban Society, which has a very specific Korean American POV. Hong serves jeon, fried disks of squash topped with caviar, because she always felt the labor-intensive dish she had as a kid deserved more respect. In Sonoma, you’ll find Korean chef Joshua Smookler, who was adopted by Jewish American parents, casually incorporating pastrami from New York’s famous Katz’s deli in his kimchi fried rice. Sitting at the chef’s counter at Comedor Lilia in Portland, chef Juan Gomez will tell you how freeing it is to cook the food of the Pacific Northwest through a Mexican lens as an expression of himself—hence his signature dish of a pork-collar confit served with pan arabe. Arjav Ezekiel, co-owner of Birdie’s in Austin with chef Tracy Malechek- Ezekiel, was never formally taught as a sommelier, but he’s managed to create one of the best wine lists in the country.

“Are we celebrating anything this evening?” The answer will always be life. But it might include more than just yours. —Kevin Sintumuang

It is perhaps unfair to ask a restaurant such as Kann, Gregory Gourdet’s revelatory Haitian eatery, which opened in August, to carry a country on its shoulders. It is also perhaps impossible to experience Gourdet’s assured debut and not consider Haiti’s troubled history and the way the country has been portrayed in news reports over the decades. Many Americans associate Haiti with instability, from the Duvaliers to Aristide to more recent coups, assassinations, and chaos. (Few remember America’s own brutal occupation there from 1915 to 1934.) It is—in both the public imagination and actual fact—a land battered by natural and man-made disasters alike, a front-page-news country when it appears in the papers at all. But of course there’s more to Haiti and to the Haitian diaspora.

What Gourdet does here, mining his own memories of growing up a first- generation Haitian American in Queens, is bring to bear on that country’s cuisine the entirety of his life experience. From the fine-dining kitchens of Jean-Georges to health-conscious cooking to the sensitivity that comes with having lived the burden of double-veiled identity, Gourdet knows that there’s “a people” and then there are people, and the balance must be finely calibrated.

From behind the counter in this gold-accented room, Gourdet negotiates that line with seeming ease. Roots ground, not bind, the menu. Epis, a sort of Haitian sofrito, is sublimated into a plant-based butter and served with golden plantain brioche. It’s also used in a tremendous brined, hearth-grilled chicken. An outstanding griyo twice- cooked pork (braised and fried) is given a shot of flavor steroids with pikliz, a Haitian slaw. Gourdet turns mushrooms sourced directly from northern Haiti into tea that he then folds with lima beans to make an earthy, trad-inspired dish called diri ak djon djons. The entirety of barbecue, developed by the Arawak people before being “discovered” by Columbus, can be divined from the restaurant’s pièce de résistance: a glistening barbecue beef rib rubbed with Blue Mountain coffee, star anise, and more, then smoked for twelve hours on mesquite and white oak. The crowd—and it is always crowded—includes many Americans for whom Kann’s Creole (pikliz, bannann peze, legim) is an entirely new language, and many others, members of the Haitian diaspora who have begun flying in from across the country, for whom this language and these flavors taste like home. At Kann, the parties meet, summoned by Gourdet’s incantatory flavors. —Joshua David Stein

“But what kind of restaurant is it?” people have asked me. Listen. It’s the kind of restaurant where you want to reserve a table for about a dozen friends. It’s the kind of restaurant where you can leave your table for a moment and walk into a little convenience store tucked toward the back to gather extra drinks and snacks. It’s the kind of restaurant where you’ll get an unforgettable salad of Shinko pear and avocado in a hot mustard vinaigrette and a platter of biscuits flooded with a Korean curry gravy, but you might also get grilled puffs of potato bread that beg to be paired with a Jewish-appetizing-style spread of smoked trout, or an abalone pot pie with spoonfuls of creamy congee under the crust, or a bowl of melon sorbet with sesame oil drizzled on top. It’s Korean American food as interpreted by two chefs, married partners Katianna and John Hong, with very different life experiences. (See “Chefs of the Year” below.) The way it all comes together is not necessarily a simple thing to explain, which is why the choose-your- own-adventure mode of dining at Yangban Society may befuddle someone who gives the menu a quick online scan. My advice: Go with that big group, order everything, let manic delight lead the way. When the food hits the table, it all makes sense. —Jeff Gordinier

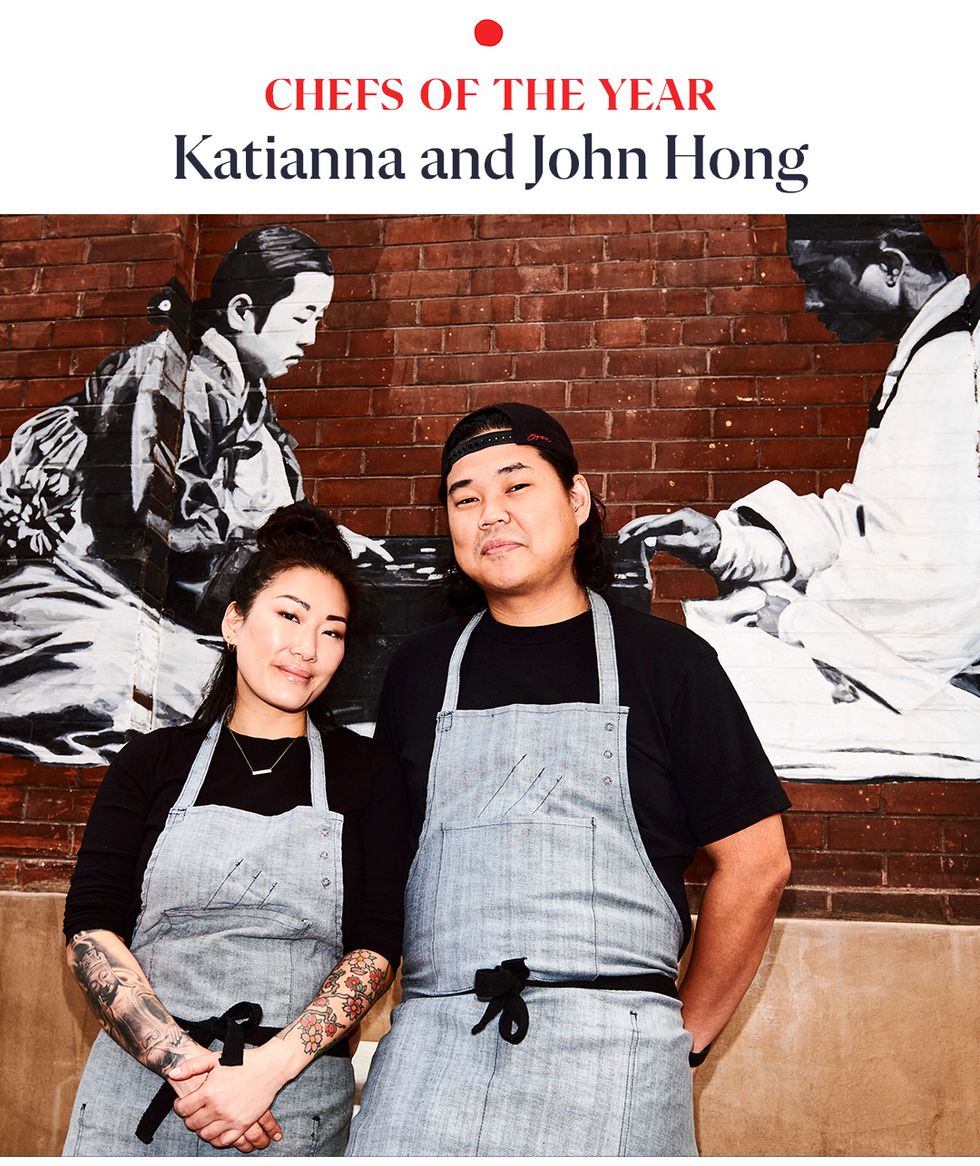

The best cooking is about storytelling. It’s a way of saying, “Here is the culture I come from, and here are some thoughts I have about that”—even if the whole time you, the hungry customer, are simply thinking, This is absurdly delicious. Like Gabrielle Hamilton’s Prune in New York, Yangban Society, in downtown Los Angeles, is an autobiographical restaurant; think of it as a memoir in the form of a menu, with married partners Katianna and John Hong as the coauthors. John grew up with a second-generation perspective in a Korean American family in the Chicago area. Katianna was born in Korea, adopted, and raised in upstate New York by an Irish Catholic mother and a German Jewish father, which is why you might find her own twist on schmears and matzo balls on the Yangban Society lineup. Yeah, they’ve got the fancy credentials—John cooked at Alinea, and both worked alongside three-Michelin-starred chef Christopher Kostow in the Napa Valley—but Yangban Society bids farewell to the fine- dining pageantry. In fact, the Hongs aren’t copying anyone. They have integrated all of their personal and professional experience to create a restaurant that no one else could create, because no one else could tell exactly the same story. It’s a Korean story and it’s an American story. It’s a Los Angeles story and it’s a family story. And no matter where your family is from, Katianna and John are somehow telling everyone the same thing: Welcome home. —J. G.

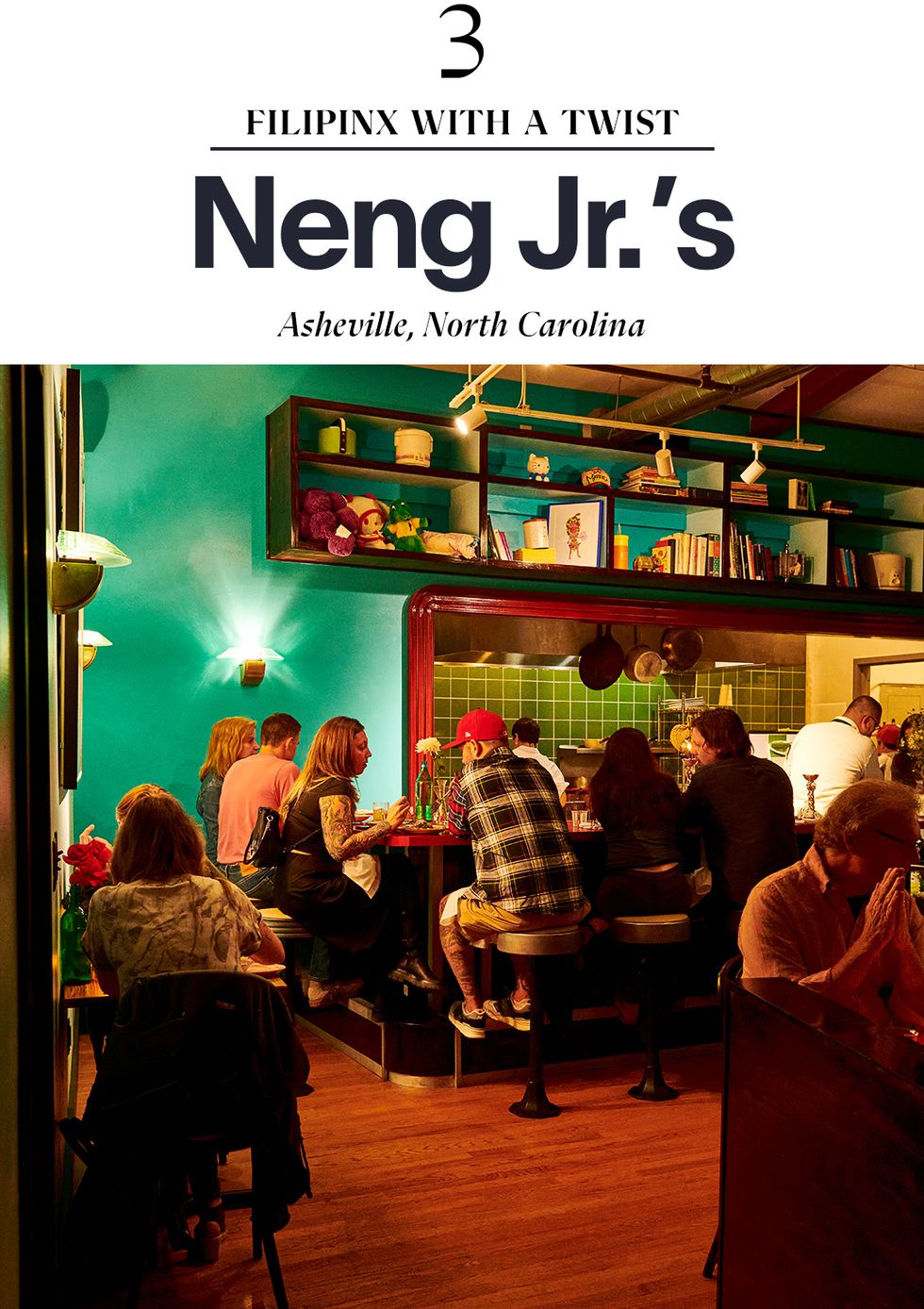

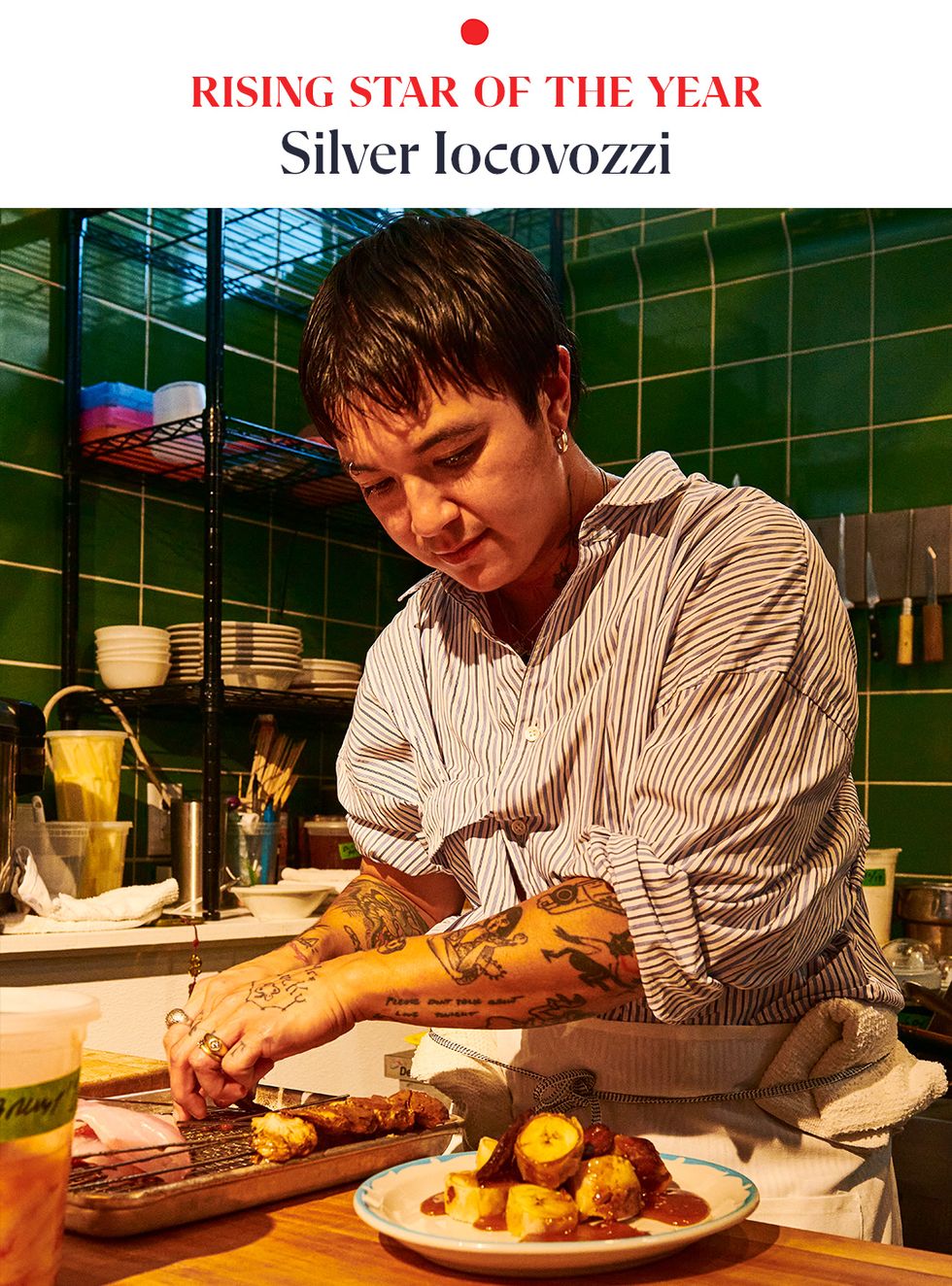

Look for the metal door in the red wall at the back of the building. Open it. Stepping into Neng Jr.’s feels like passing through a portal into a cozy, Technicolor, genderqueer version of Rick’s Café from Casablanca. Stand by the bar and let Cherry Iocovozzi pour you a glass of natural wine. Take your seat and prepare yourself for a trippy carnival of flavor courtesy of chef Silver Iocovozzi (our Rising Star of the Year), who’s married to Cherry. There’s an entire eggplant blackened on top of live coals, split open, and doused with acidic, herbaceous relish. There’s a sliced duck breast floating in an adobo sauce that tastes like Christmas gravy by way of Manila. There are tablets of seared foie gras tumbled on top of turon, the snack from the Philippines in which a banana is encased in a deep-fried crust. Everything sings loudly and proudly like a new form of music you’ve never imagined. Ideas and ingredients from the Philippines and France and the American South join hands and dance as if they’re finally free to do whatever they want. —J. G.

Asheville, the bohemian city in North Carolina, has a lot of great food, from Spanish (Cúrate) to Indian (Chai Pani). But until Silver Iocovozzi (and husband Cherry) opened Neng Jr.’s this past summer, it didn’t have a Filipinx restaurant. Worth the wait? Oh yeah. Iocovozzi works like a wizard, moving effortlessly in the tiny kitchen while giving new life to the hackneyed phrase “cooked to perfection.” Snapper: just right. Duck: just right. Eggplant: damn, scorched on the outside but creamy and spoon-ready within. Just right. The restaurant is named after Iocovozzi’s mother, Neneng. That’s her dancing at the center of the painting that presides over the room. Come with an open spirit and Iocovozzi might chat with you about the cuisine of the Philippines, sure, but a conversation could also detour into swooning over muscadine grapes or dreaming about what Eric Ripert is doing at Le Bernardin in New York. Both the cooking and the conversation give you a taste of it: This is just the beginning. Silver Iocovozzi can do anything. —J. G.

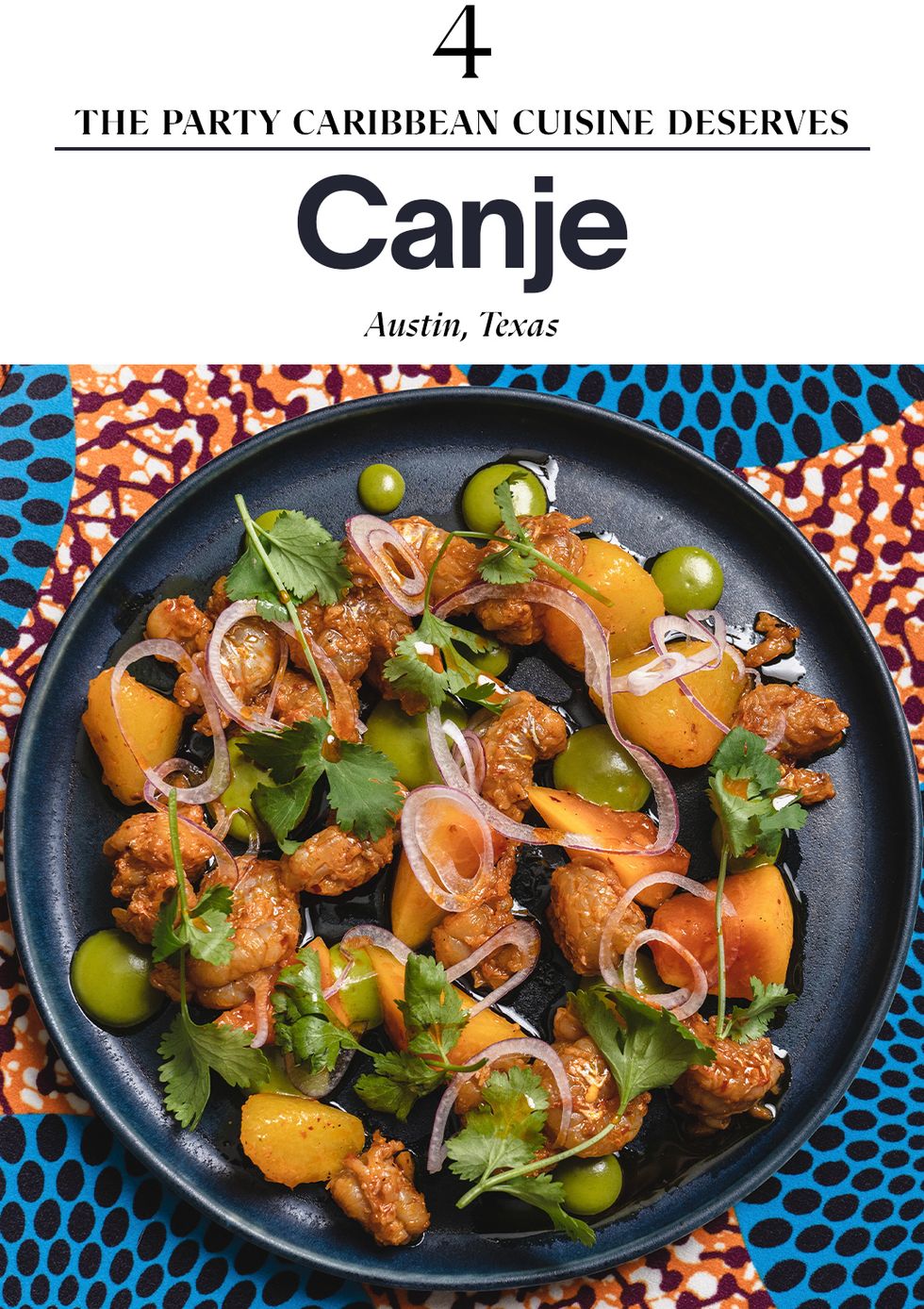

Ask chef Tavel Bristol-Joseph about cassareep—a key ingredient in luscious, wild- boar pepper pot, the national dish of his native Guyana—and he’ll tell you that the store-bought versions of the cassava-based black liquid weren’t cutting it. So he convinced a relative to fly over to Austin with cassareep on the regular. Such time and devotion is the magic behind Canje. The marinade of the jerk chicken is fermented, giving the meat an impossibly deep flavor and smokiness. And the fruit in the black cake dessert is soaked in rum for months—the starter for the cake that I had was older than the restaurant itself. And as the night rolls by, it can all start to feel like a celebration. Welcome to the party. —K. S.

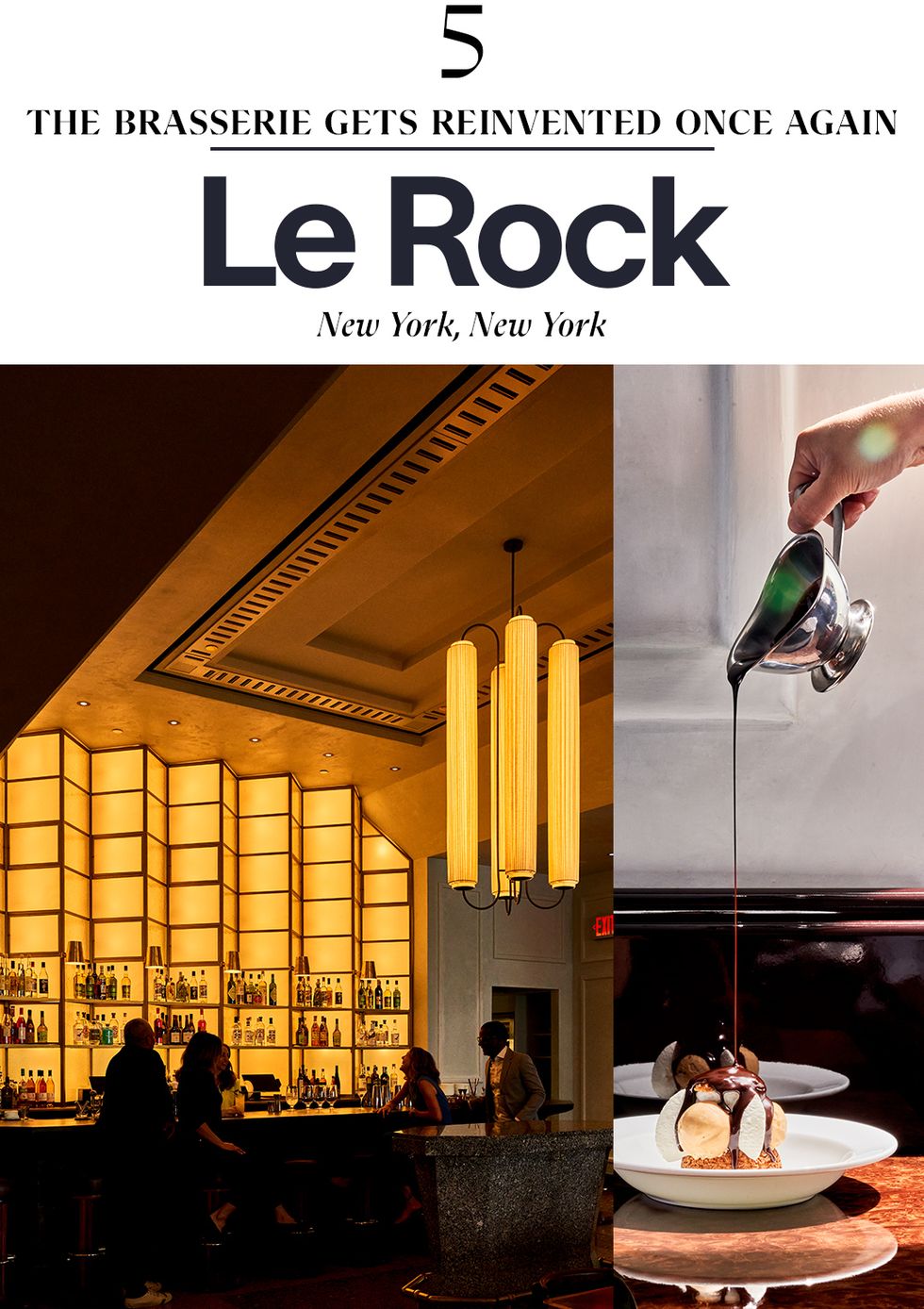

Sometimes the cover is better than the original. Consider Charles Bradley’s cover of Black Sabbath’s “Changes,” Sinéad O’Connor’s of Prince’s “Nothing Compares 2 U,” and Lee Hanson and Riad Nasr’s version of leeks vinaigrette at Le Rock. Messrs. Hanson and Nasr, the duo behind the downtown darling Frenchette, reinvent the classic as a vegetable striptease, in which the dark charred leaves are undressed tableside to reveal the tender pearly leeks inside. This is just one of the many revelations of things you thought you knew that take place in the buzzing room in Rockefeller Center. Steak au poivre becomes tender bison. Amidst a mess of agnolotti, chunks of chestnut are tossed among black trumpet mushrooms. Both willy-nilly and considered, that old chestnut finds a new life on the plate. —J. D. S.

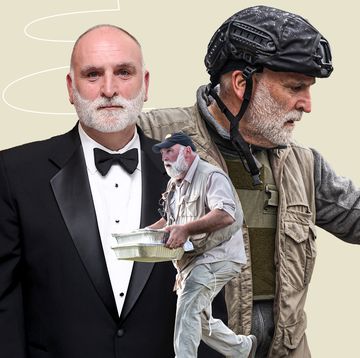

ESQUIRE: What changes have you noticed in American restaurants over the past forty years?

JOSÉ ANDRÉS: Farmers feed America, and we as restaurants have gotten better at sharing their story, but there is still more to do. The connection we have between the bounty of the land and feeding the people needs to improve.

ESQ: What changes still need to happen?

JA: We have so much to focus on when it comes to feeding our country. There is a huge opportunity with the food that people are throwing away, like imperfect produce, and we must look at how we can make it all into nutritious, tasty food for those in need.

ESQ: What’s the best American restaurant of the past forty years?

JA: One?! When we have so many amazing restaurants? Well, if you make me. . . . It’s hard to top the magic that my dear friend Patrick O’Connell has been making in Virginia at the Inn at Little Washington decade after decade. No matter how much time passes between visits, when I go back I always feel right at home.

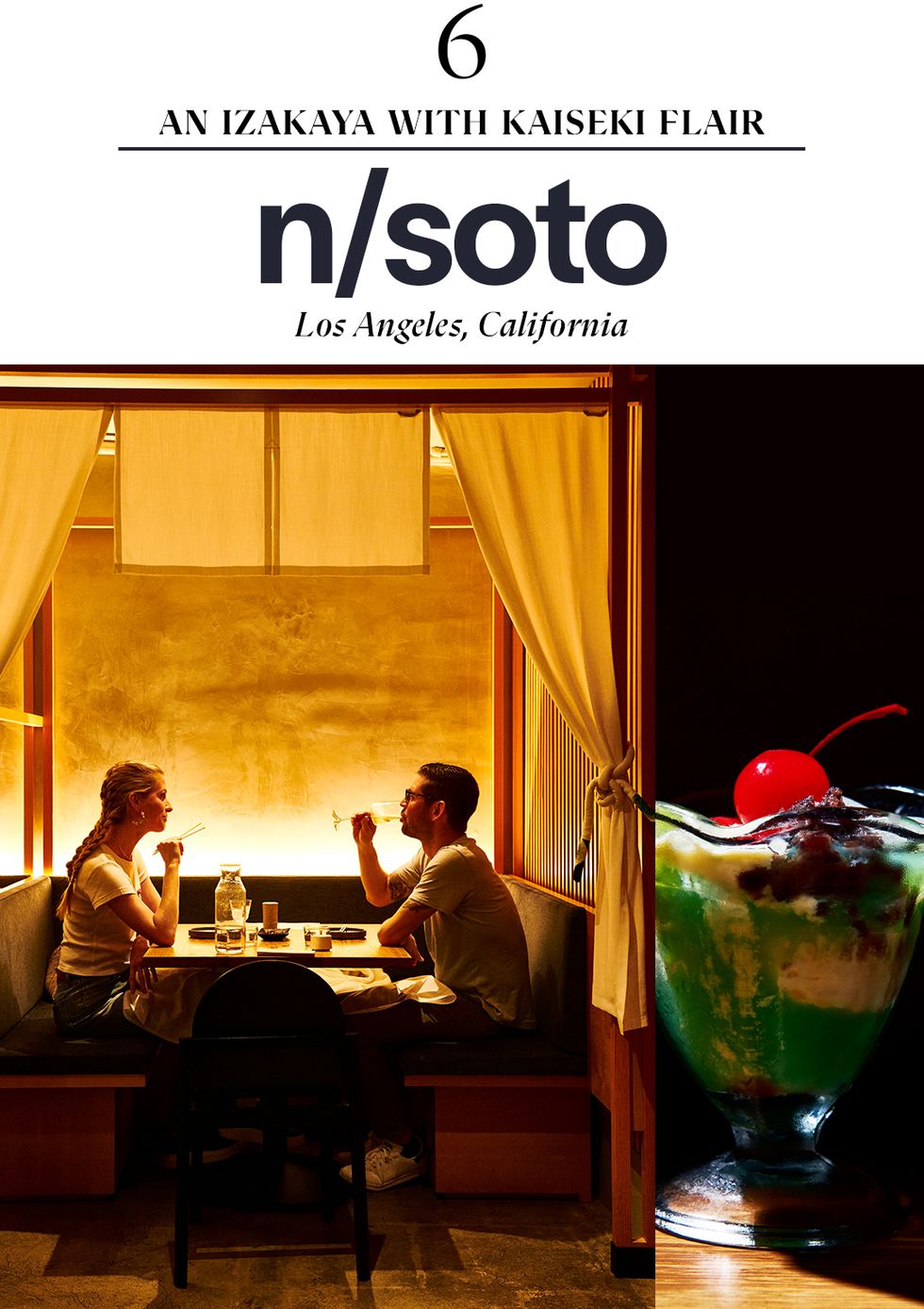

There’s a playfulness at n/soto that may surprise anyone who’s accustomed to the meticulous, season- revering kaiseki cuisine that’s associated with Niki Nakayama and Carole Iida-Nakayama’s famous flagship, n/naka. (As in: a sundae capped with a cartoony green froth of Japanese soda.) There’s lusty extravagance, too. (As in: a salad of warm Brussels sprouts tossed with salmon skin and a poached egg, and a roasted marrow bone that’s caked with an earthy miso glaze. You scoop out the fat and the sweetness and smear it on yaki onigiri.) Paradoxically, though, it’s the subtlety of the experience that could wind up sticking with you—gentle undercurrents of flavor that you maybe didn’t expect to find in the drinking den of an izakaya and that reflect the married duo’s attention to nuance and tradition and balance. (As in: the way jellied, vinegary cubes of tosazu rest in the deep cups of Kusshi oysters, fostering a duet as delicate as sherry and cream.) —J. G.

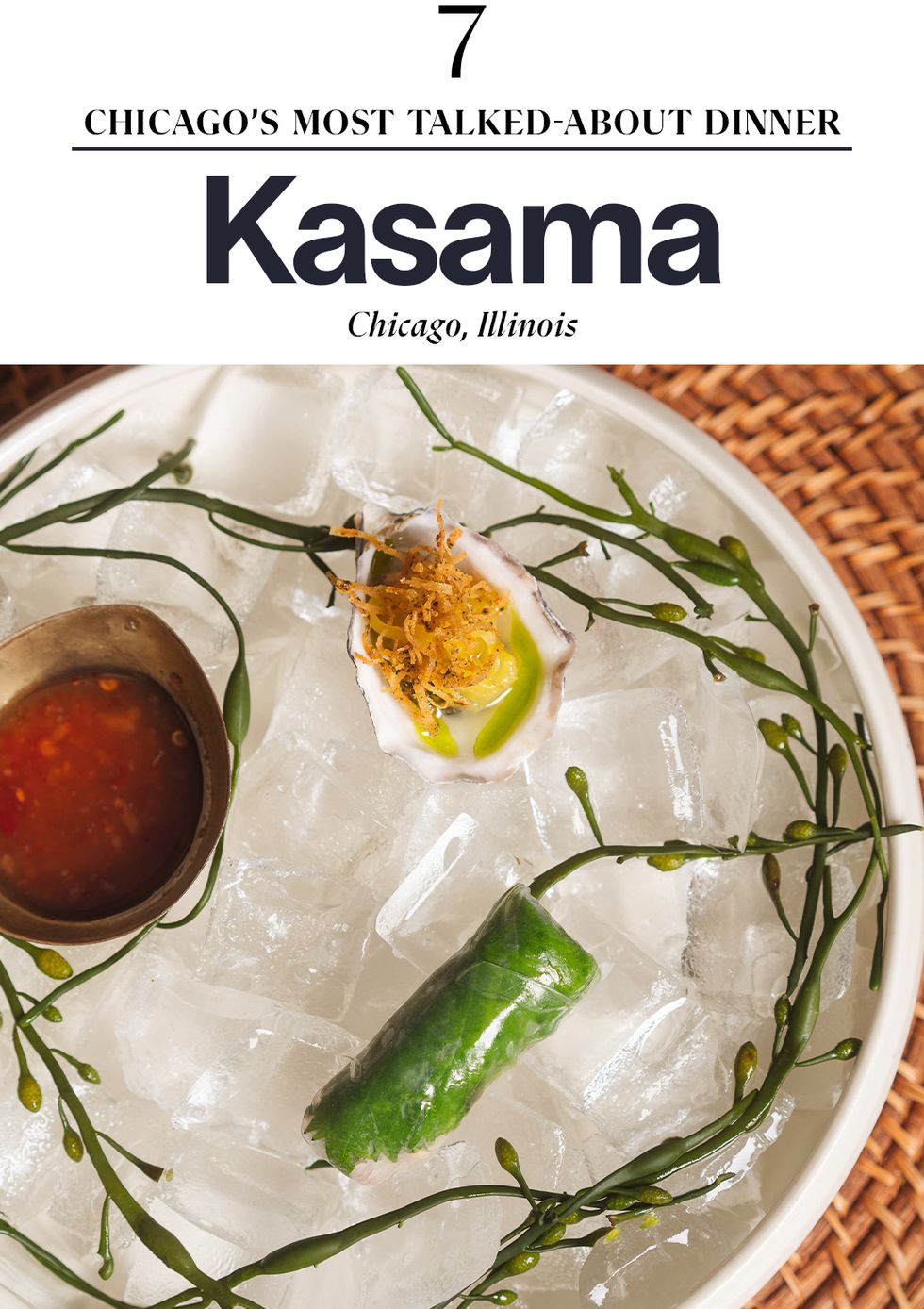

“Have you been to Kasama?” Everyone in Chicago asked me this when I asked them what restaurants they were excited about. “Only for breakfast,” I said, to which they replied: “You need to go for dinner.” When it started as a morning venue for Genie Kwon’s exquisite baked goods and Tim Flores’s mouth- watering longanisa, egg, and cheese sandwiches, we loved it enough to put it on our Best New Restaurants list last year. But the dinner service it’s rolled out since then feels like an entirely different venture: Filipino food served with impeccable precision and finesse in a tasting- menu format. You bite into the humble lumpia, which arrives early, and think, This might be the best lumpia ever. The nilaga, composed of cabbage, bone marrow, and fluffy short-grain rice, has the uncanny ability to evoke what you would eat on a rainy day as a kid. There is a croissant toward the end with a shower of truffles. All of this made us believe: People need to know about the p.m. version of Kasama, too. —K. S.

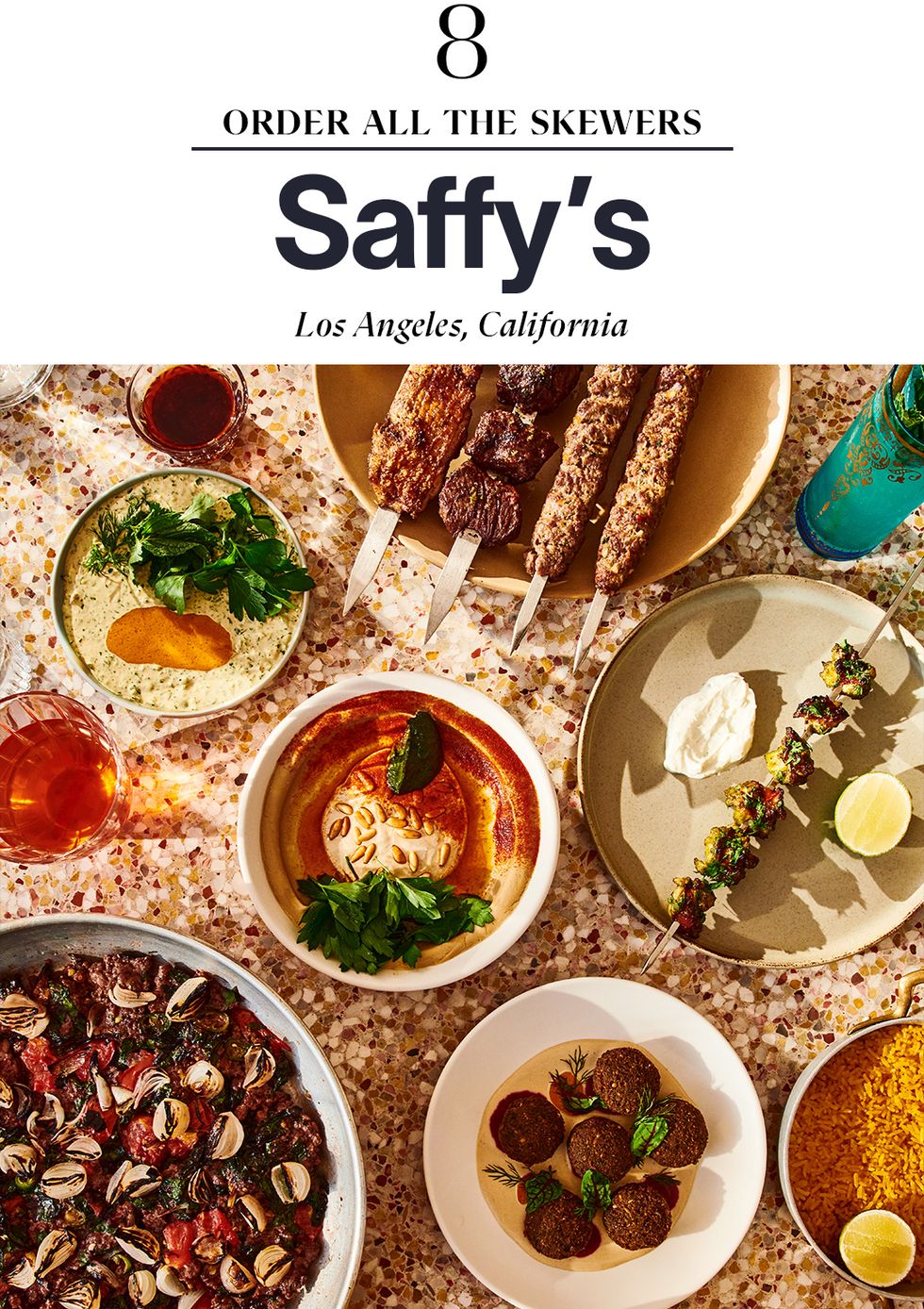

Yes, you must get kebabs. But before that, lobster. Served on a metal skewer and dressed in a green harissa sauce with a sprinkle of cilantro shoots, it is cooked over wood yet impossibly tender and sweet. It can be shared, but you probably won’t want to. And yes, the kebabs, but wait, can we talk about the $26 shawarma? You’ve had plenty before, but nope—this is something else. Incredibly light laffa, a simple vessel to hold the lamb and beef, which have been slowly kissed by heat on a spit displayed proudly like a trophy in the open kitchen. It is dressed gently, with tahini, a pepper relish, tomato, lettuce, onion. Best shawarma ever? It’s up there. Finally, the kebabs: Go for the lamb, redolent of cardamom, or the chicken, imbued with cumin, sumac, and cinnamon. They all come with chili crisp. Wow. Take in the loud room in its golden gloriousness, like a café in Tel Aviv at sunset. Ori Menashe and Genevieve Gergis had two bona fide L. A. hits with Bestia and Bavel. Now, with Saffy's, they have three. —K. S.

You might think you’ve accidentally entered an art gallery in East Nashville, but make no mistake, you’re at Sean Brock’s shrine, which houses not one but two wildly different restaurants. Downstairs is Audrey, where everyone is in emerald booths dining on plates of southern fare with finesse: red grits and johnnycakes and rosy-centered rib eye with charred okra. Upstairs, past the glass-encased lab, is June, an avant- garde tasting-menu journey flavored with elements developed in the lab—think pinto-bean miso and peach-pit nocinos, truffle-topped huckleberry fruit leathers and caviar with black walnut and sassafras. It’s like the Noma of the American South. —Omar Mamoon

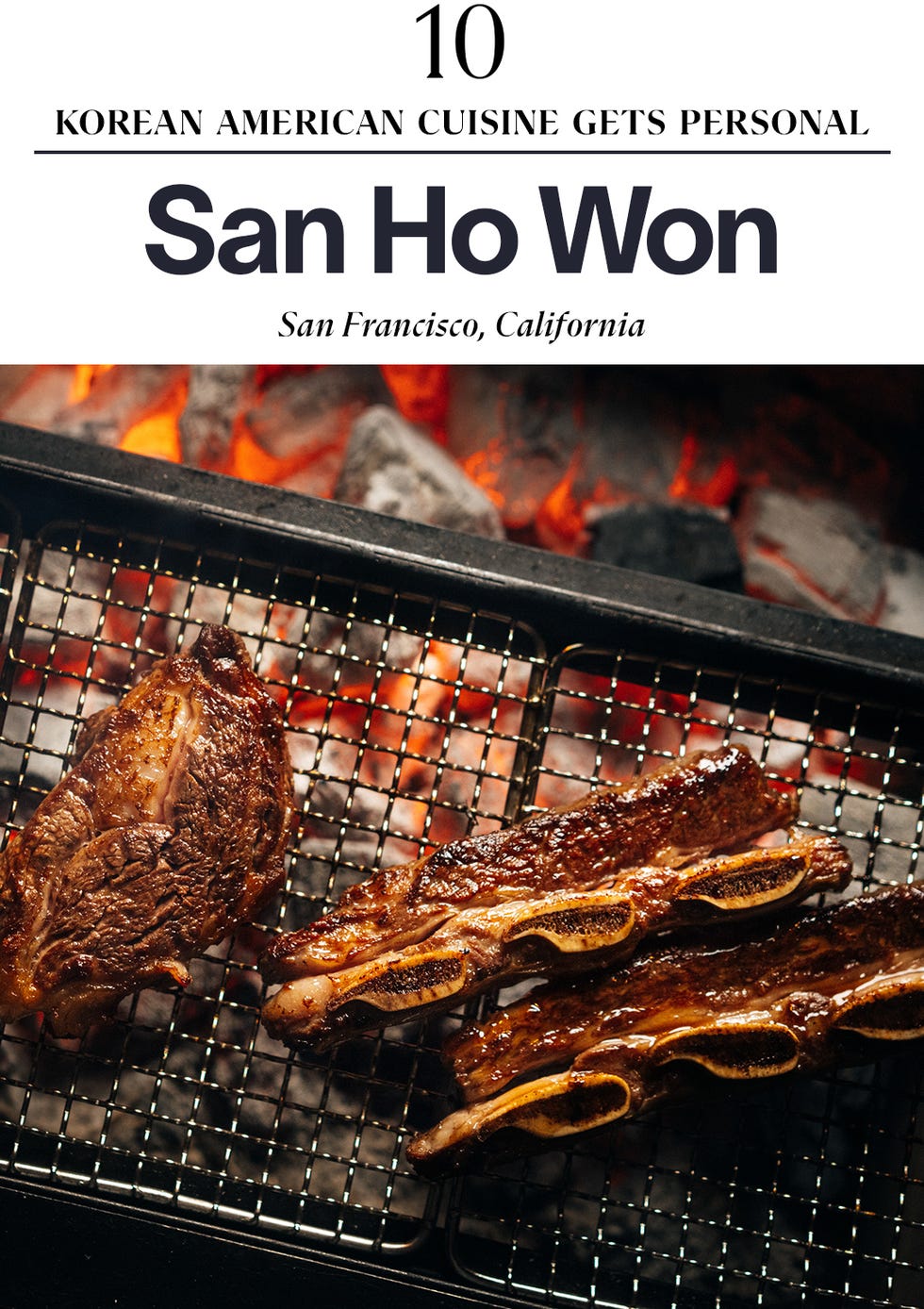

Walk up to the shiny white exterior of San Ho Won, Jeong-In Hwang and Corey Lee’s Korean restaurant, and peek through the window and you’ll see the minimalist dining room, packed with patrons gleefully gobbling double-cut galbi (short ribs) and meticulously constructing lettuce- leaf ssam wraps filled with tender beef tongue. But there are no tableside gas grills. This isn’t your typical grill-your-own setup; instead, each meat is carefully cooked over specially sourced white lychee charcoal in an open kitchen. Be sure not to miss the gleaming galbi mandu (griddled beef dumplings) or the bubbling cauldrons of kimchi jjigae pozole that will warm your soul on even the coldest San Francisco night. —O. M.

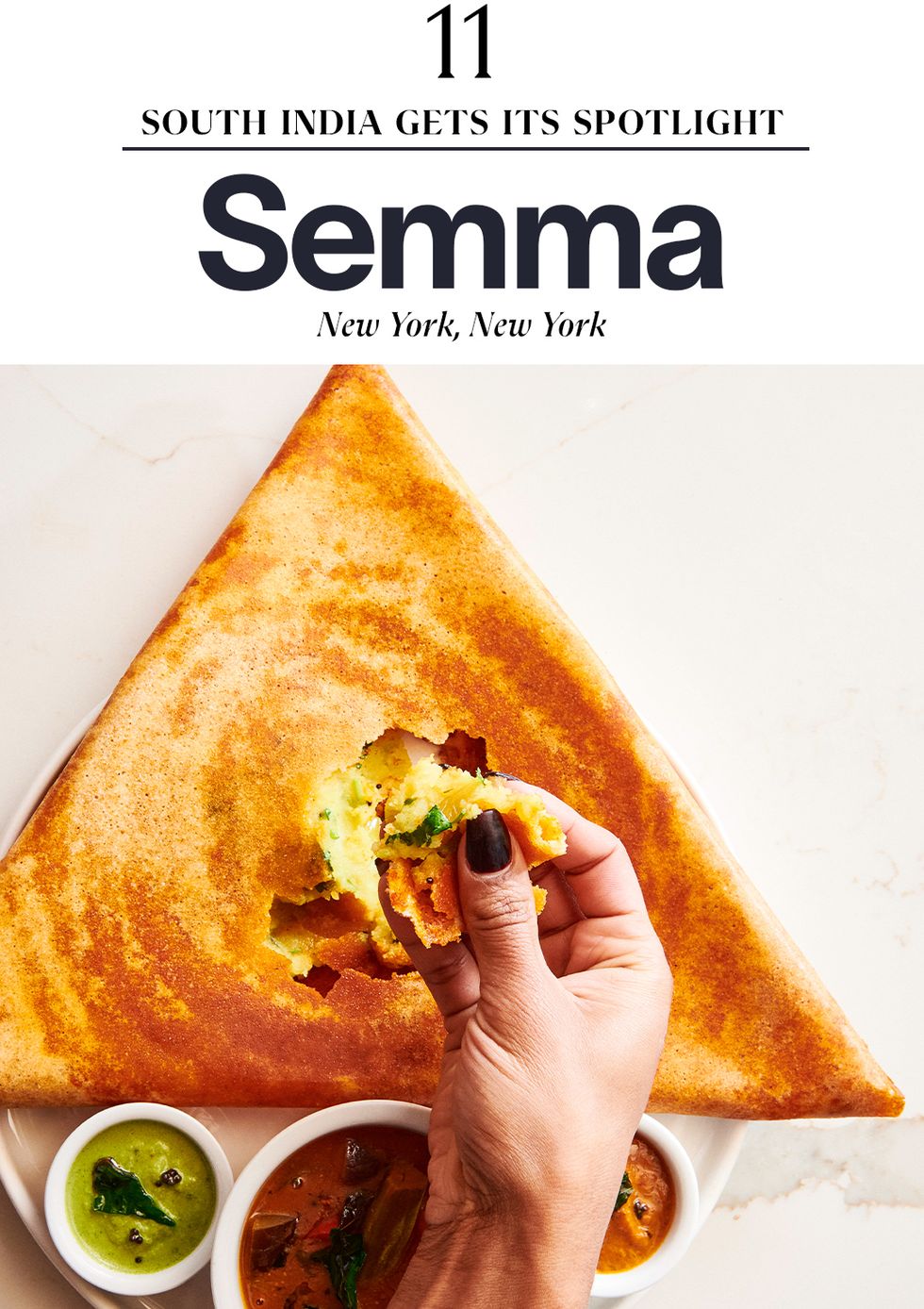

Having altered the landscape for Indian food in the United States with the Nevermind-like zeitgeist blast of Dhamaka (our number-one Best New Restaurant last year), restaurateurs Roni Mazumdar and Chintan Pandya wasted no time in delivering a follow-up in Semma. They recruited chef Vijay Kumar, a native of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, to develop a menu that would focus on the cuisines of southern India—and that would do so in the same spirit as Dhamaka, meaning no compromises. The result is a festival of delights that many New Yorkers had never before encountered. Meat dishes (oxtail, venison, goat intestines) lure you into deep caverns of flavor; nathai pirattal, a dish of Peconic snails that you wrap in little pancakes, sounds like a curiosity but quickly turns into a craving. And then there’s Kumar’s gunpowder dosa, both ethereal and epic, a feat of technique that’s so delicious I returned for it four times. —J. G.

ESQUIRE: What changes have you noticed in American restaurants over the past forty years?

ERICK WILLIAMS: Good: the increase in pay for back-of-house employees, better benefits, and more opportunity for chefs cooking the food of their ethnicity and culture. Bad: Staffing and work ethic are at an all-time low, and customers are more entitled than we have ever seen.

ESQ: What changes still need to happen?

EW: There need to be clearer paths to capital for small and independent operators. There is still a ton of work to do in regards to recognizing food and culture of every walk. ESQ: What’s a dish that you consistently order whenever you walk into a restaurant? EW: Biscuits, bone marrow, octopus, sardines, steak tartare.

ESQ: What’s a dish that you’d happily never see again?

EW: Lobster mac and cheese.

ESQ: In your opinion, what’s the best American restaurant of the past forty years?

EW: Canlis [in Seattle].

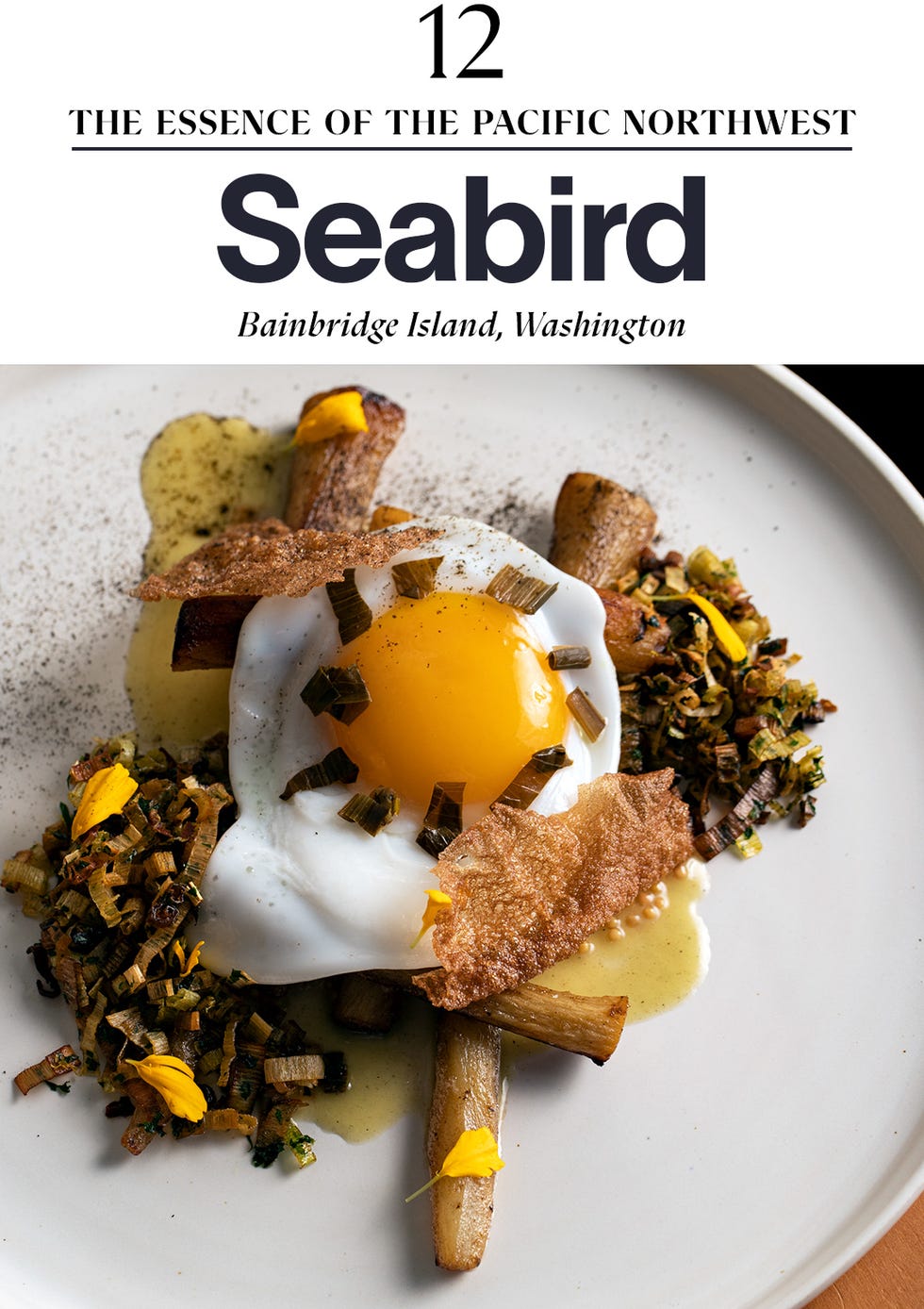

Sometimes, to get to the best restaurants, you gotta go the distance. To reach Seabird on Bainbridge Island, you take a ferry from the edge of Seattle. But what chefs Brendan McGill and Grant Rico (SingleThread alum) do with the bounty of the Pacific Northwest makes the journey worth it. Creamy uni French toast, halibut ceviche with zippy leche de tigre and jalapeño crema, and sablefish in a delicate almond broth fortified with spicy salsa macha are just some of the reasons you’re here. But you would be remiss to miss the vegetables—they’re just as compelling as their oceanic counterparts. The roasted salsify slathered in a brown butter sauce and served with a rich, runny duck egg and roast carrot fricassee will make you think of vegetables in a whole new way. —O. M.

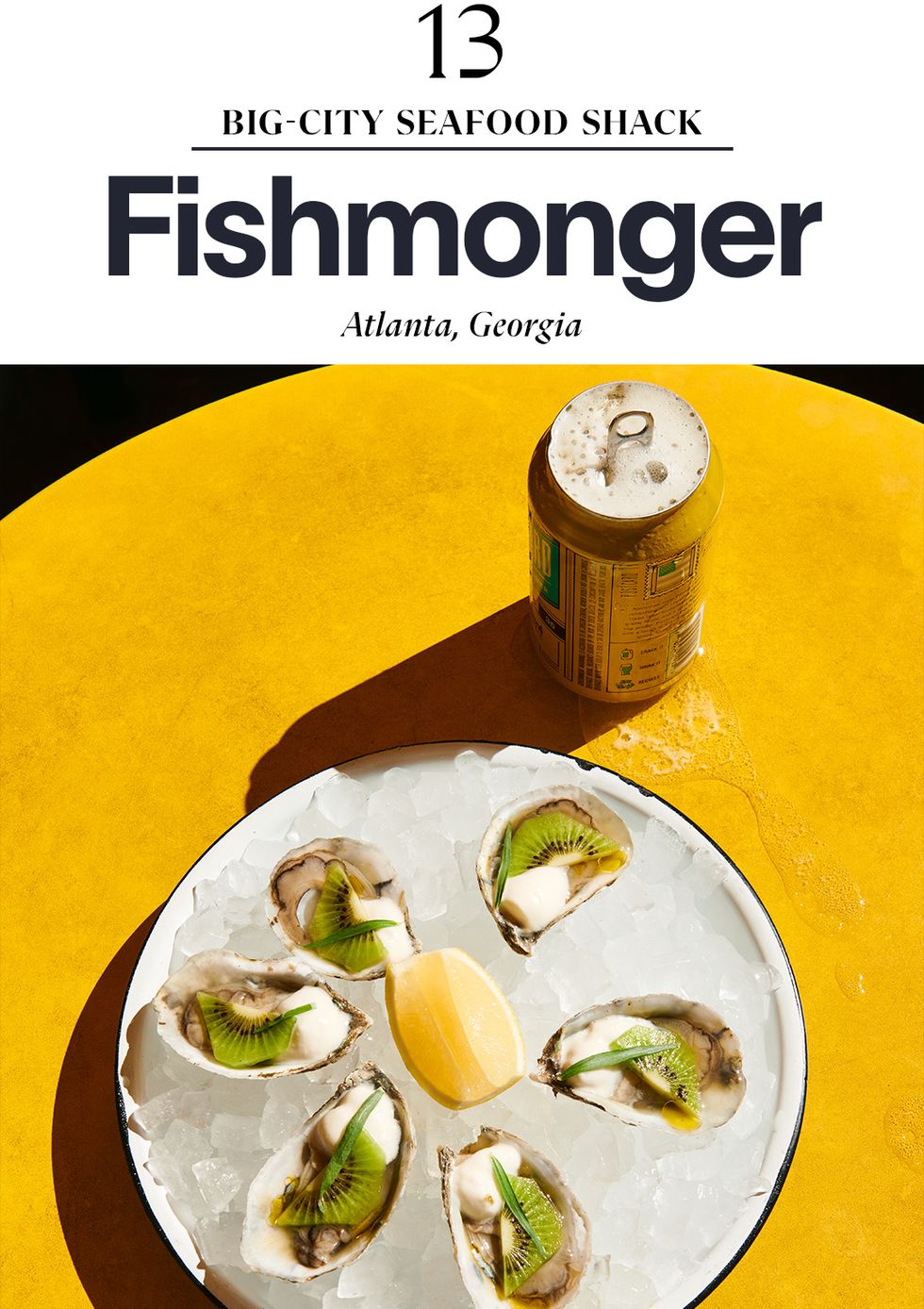

Mongering has a mixed reputation. Rumors, war, and whores on one side; knives, cheese, and fish on the other. Fishmonger, which debuted in May, tips the scale in mongering’s favor. It channels the seaside fish markets of the Gulf Coast, where fresh catch is available but weirdly fried to oblivion. At Fishmonger, chef Bradford Forsblom forgoes the deep fryer entirely. A hot catfish sandwich comes to the table glistening with chili paste, atop a nori- buttered Martin’s roll. Blackened grouper is dark as night on the outside but lily white within. All this is eaten either on the sidewalk or at a singular high- top table as fresh snapper, grouper, and kingfish— most run up from Florida by small fishermen—stare unblinkingly from their beds of ice. —J. D. S.

ESQUIRE: What changes have you noticed in American restaurants over the past forty years?

WOLFGANG PUCK: We now have world- class restaurants almost in every city. We pro- duce some of the best wines, and above all, we have so many talented American chefs who are equal to those in France, Italy, and everywhere else in the world.

ESQ: What’s a dish you always order?

WP: I always order a good bottle of wine.

ESQ: What’s a dish that you’d happily never see again?

WP: Dishes that were influenced by molecular gastronomy, which is more show-offy than flavor focused

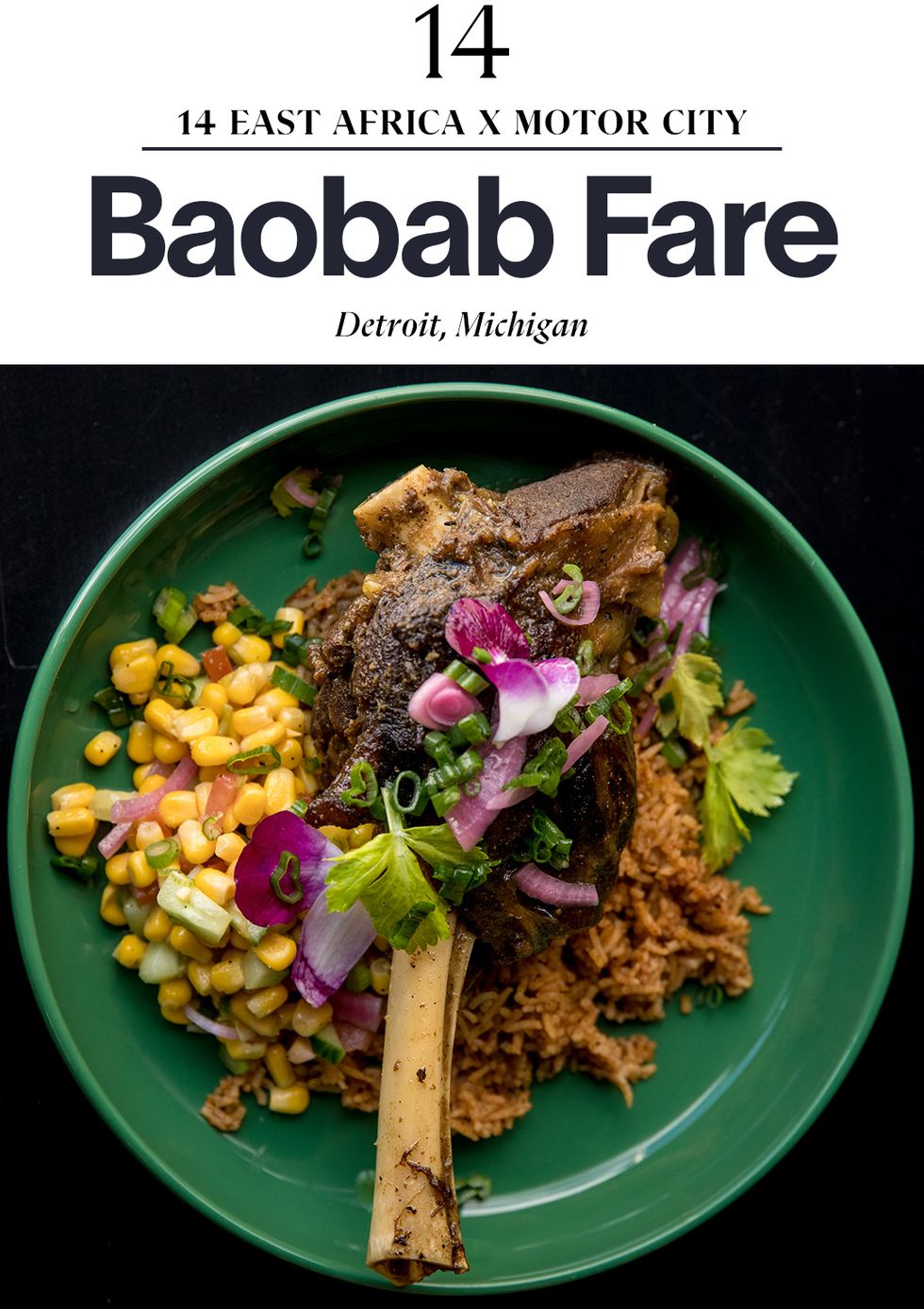

There are ten Burundians in Detroit, and at least four of them, at any given moment, are at Baobab Fare. This includes its owners, Nadia Nijimbere and Hamissi Mamba, and their twin nine-year-old daughters, who are flitting around the dining room giggling. It’s not exactly a hometown market, but the light-filled restaurant in New Center is perpetually full. Detroiters come for Nijimbere’s concise menu of underrepresented East African classics. Homemade ugali, a bite similar to fufu, is served with a hearty okra stew. A G.O.A.T. goat shank called mbuzi is long-stewed and tender as a caress. Atop crispy fried fish come onions of peculiar tang, beside plantains of particular sweetness and stewed yellow beans of immense complexity. This in itself is life-affirming. But Baobab has also become a gathering place for asylum seekers, immigrants, local office workers, teams of community activists. The restaurant’s namesake, the baobab tree, is called the tree of life, for it both endures arid conditions and fosters life around it. Never has there been a restaurant more deserving of the name. —J. D. S.

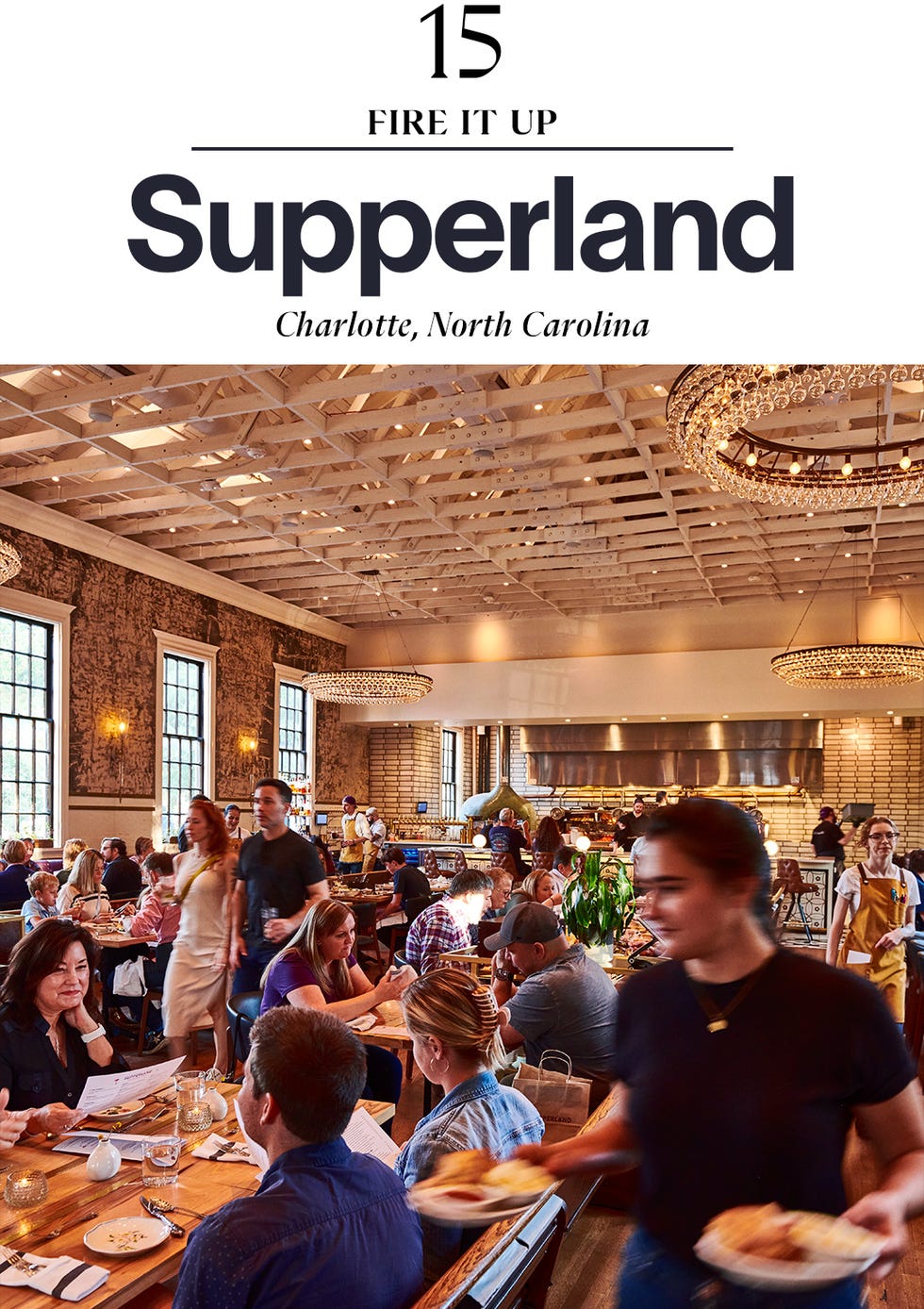

I sat at the counter, where I could watch sparks fly from the wood fires, and it didn’t take long before two women were sharing food with me—and I with them. Supperland’s that kind of joint. It’s a former church that owners Jamie Brown and Jeff Tonidandel have converted into a celebration of tender steak, onion dip, potato chips, and fellowship. I ate dishes that seemed blessed by some kind of spirit. A cazuela full of blackened onions arrived hissing steam. As a guy poured hot butter onto my platter of roasted oysters, a glowing- orange remnant of firewood dropped right on top of one of the bivalves. “Don’t eat the ember,” a server advised. Lord, have mercy. —J. G.

The cocktails at North Carolina’s Supperland aren’t just layered and delicious. They are thoughtfully woven into the very experience of dinner, particularly in the restaurant’s downstairs speakeasy. You have Colleen Hughes to thank for that.

Esquire: What’s your philosophy about pairing food and cocktails?

Colleen Hughes: I believe that cocktails can lend themselves better to food pairings than wine can, especially when you’re using more of a culinary approach. We handcraft each individual ingredient for each cocktail, with the exception of the spirits themselves, allowing us the freedom to use any flavor, spice, salt, or acid that is out there.

Esq: What’s a spirit more diners should try?

CH: Amari—and amaro cocktails—especially at the beginning and at the end of meals. Finishing with a bitter amaro like Fernet or Averna helps settle your stomach

and bring you out of your food coma so that you enjoy the rest of your night. They’re medicinal spirits. They can make you feel better. —J. G.

In case you’re wondering how to categorize, say, a trout crudo with Concord grape aguachile, it’s right on the menu: “Pacific Northwest cuisine through the lens of a Mexican-American chef.” That chef is Juan Gomez. Restaurateur Angel Medina and culinary director Olivia Bartruff, part of the team behind República, the Mexican tasting-menu spot that’s a pillar of Portland’s dining scene and where Gomez was chef de cuisine previously, felt that he deserved his own restaurant. And so was born Lilia, a joyous deep dive into the hyper-seasonality of the region’s bounty. In the fall, the apple-cider doughnut, graced with marigold dust from flowers Gomez’s wife picks, is a perfect, fleeting conclusion. —K. S.

I noticed it while procrastinating during my senior year of college.

I was flipping through the October 1987 issue of Esquire when I spotted an article titled “Oddballs.” The piece raised a toast to three “off the beaten track” cocktails that an adventurous reader might be inclined to seek out— “drinks for those times when ‘the usual’ is just too damned usual.”

The first of the three? The negroni.

The negroni is ubiquitous at restaurants now—even overexposed, appearing in a rainbow of hues that depart from the traditional Atomic Fireball red—so it might surprise you to learn that in the same year that gave us Oliver Stone’s Wall Street and Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities, the average Esquire reader viewed it as an oddity. I, too, was something of an oddball in 1987, so I sought out this Italian cocktail with the diligence of a stalker, especially once I moved to Manhattan to write for magazines.

But even then, bartenders tended to serve me a blank stare if I tried to order it.

(Or they botched it altogether, sidestepping the negroni’s tripartite alchemy and simply pouring me a watery bowl of Campari with a splash of gin.) I eventually tasted a proper negroni at a midtown restaurant called Palio, and it was love at first sip: sweet, bitter, floral, layered with secrets. Gradually I watched the negroni move from the margins to the mainstream. Yes, it’s lovely now that I can order a decent one wherever I go, but I can’t help feeling a different sort of tripartite alchemy— equal parts nostalgia, bemusement, and whiplash. —J. G.

Randy Newman serenaded Utah. Skynyrd sang of Alabama, and Denver mooned about West Virginia. But who ever sang ballads of Arizona? Valentine, an all-day restaurant in a former dry cleaners in Phoenix, is the closest thing the Grand Canyon State might get to a love song, but it’s a sweet one indeed. Its chef, Donald Hawk, turns out a menu as electric as the sun setting over Camelback Mountain, all while celebrating the vast horizon of southwestern cuisine. The local products read like terms of endearment: pork-belly tepary beans, chiltepin mignonette, native-seed tahini, Arizona Wagyu (as used in the burger here). Would the tangle of homemade tagliarini with Asiago from the nearby high-desert Hassayampa River Valley, topped with crispy corn from Sacaton, be at home anywhere but the Valley of the Sun? Certainly not. —J. D. S.

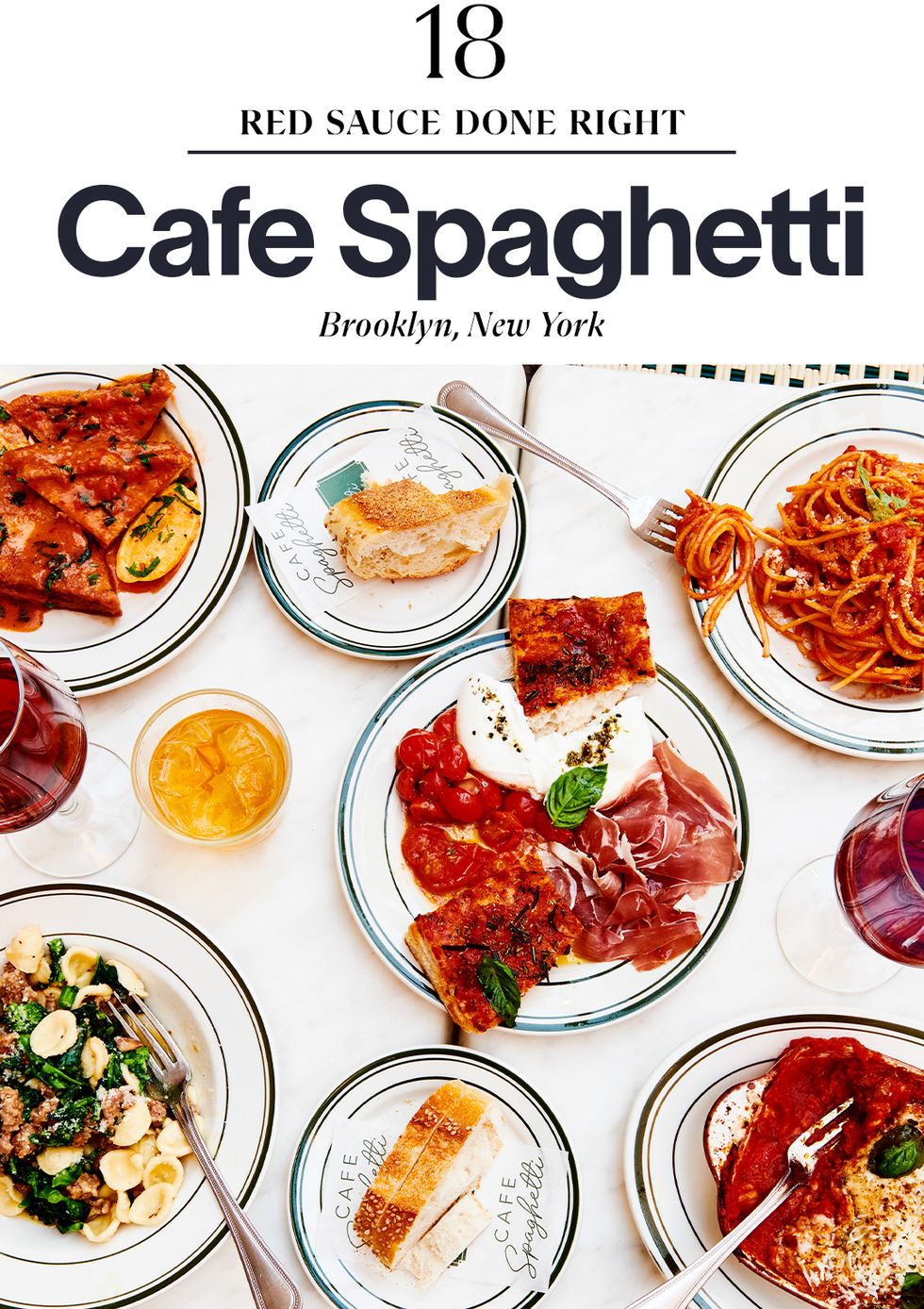

First off, the spaghetti pomodoro. You need to order that. No arguments. Yeah, we know it’s simple — tomato sauce on strands of pasta — but simple is the space in which true chefs reveal their skill, and chef Sal Lamboglia is a low-key red-sauce virtuoso. The notion of soul in cooking remains subjective and elusive, but if you can’t detect the Italian American soul that Lamboglia pours into that pomodoro and his fresh mozz and eggplant parm and spiedini alla romana (which is basically a grilled cheese sandwich bathing in funky, lemony gravy), you need help. So let us (and Giovanna Cucolo, who runs the place) help you: nothing restores the soul like sitting under an umbrella out by the Vespa in Cafe Spaghetti’s backyard on a summer evening. That and a slab of Sal’s father’s tiramisù should bring you back to life. —J. G.

Esquire: What changes have you noticed in American restaurants over the past forty years?

Nancy Silverton: The good: the growth of farmers markets and the inclusion of their goods on today’s menus. On the bad side, I think this whole phenomenon of so-called “influencers” is borderline absurd.

Esq: What’s a dish that you always order?

NS: A simply grilled whole fish that was swimming last night. Or, even better, this morning.

Esq: What’s a dish that you’d happily never see again?

NS: A salad with strawberries.

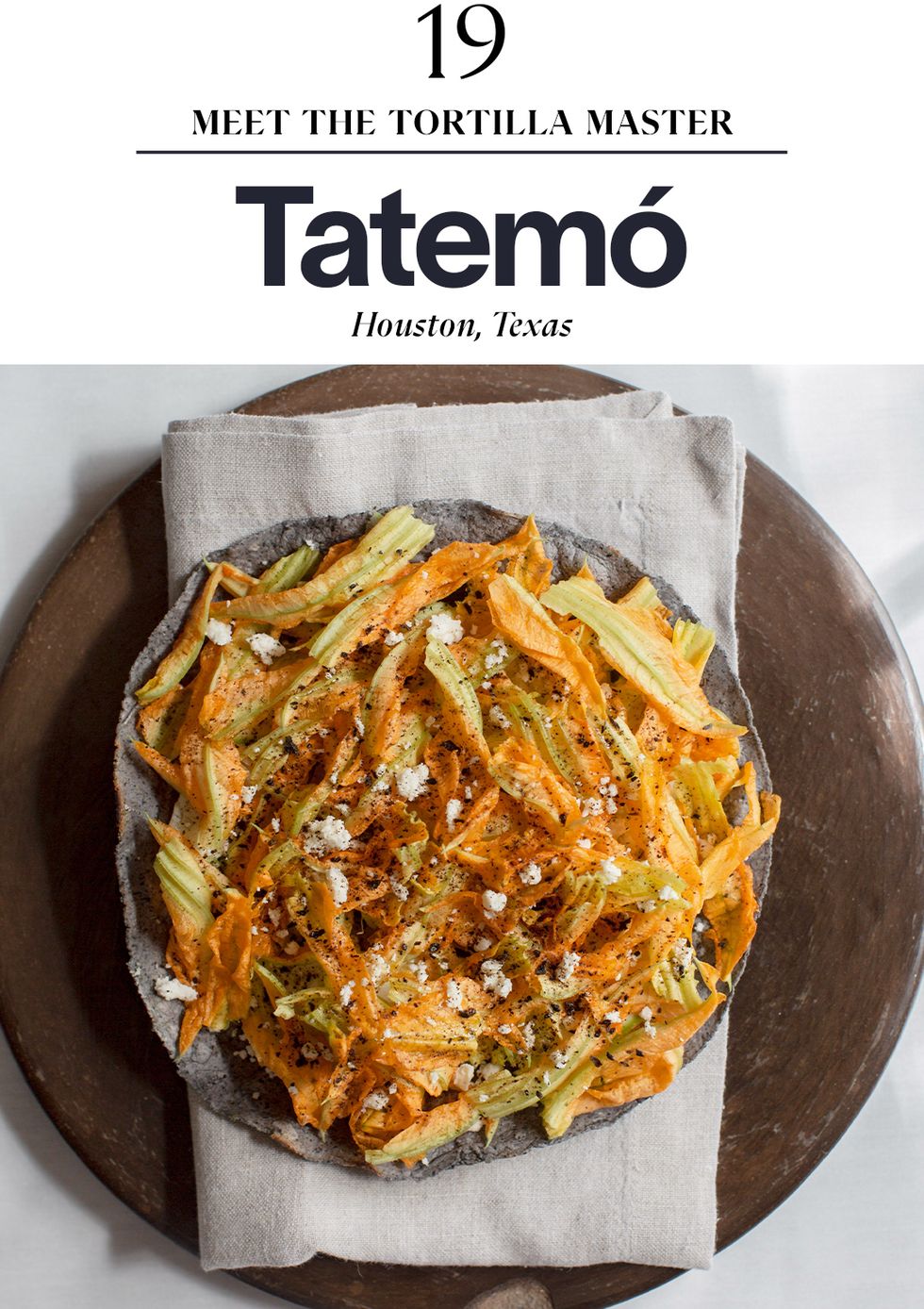

Emmanuel Chavez is a maize obsessive. For the past two years, the Mexico City–born, Houston-raised chef has sold his nixtamalized masa to corn cognoscenti on Instagram. Now he and his partner, Megan Maul, have a permanent home. Everything at Tatemó is meant to keep the focus on the Chavezes’ beloved corn. The thirteen-seat space has all the charm of a waiting room. Fifty-five-pound sacks of corn from Mexico are stacked against the wall. All the better for the vibrant characters Chavez liberates from his heirloom varieties over eight courses. The jagged purple shards of totopos, made with Yucatán’s xnuuc naal, are nutty and sweet. Cacahuazintle maize is transubstantiated into a rich, amber, corn-driven consommé. A purple quesadilla is made with Cónico Azul from the highlands of Mexico. Corn has always been a character actor. Here it’s the leading man. —J. D. S.

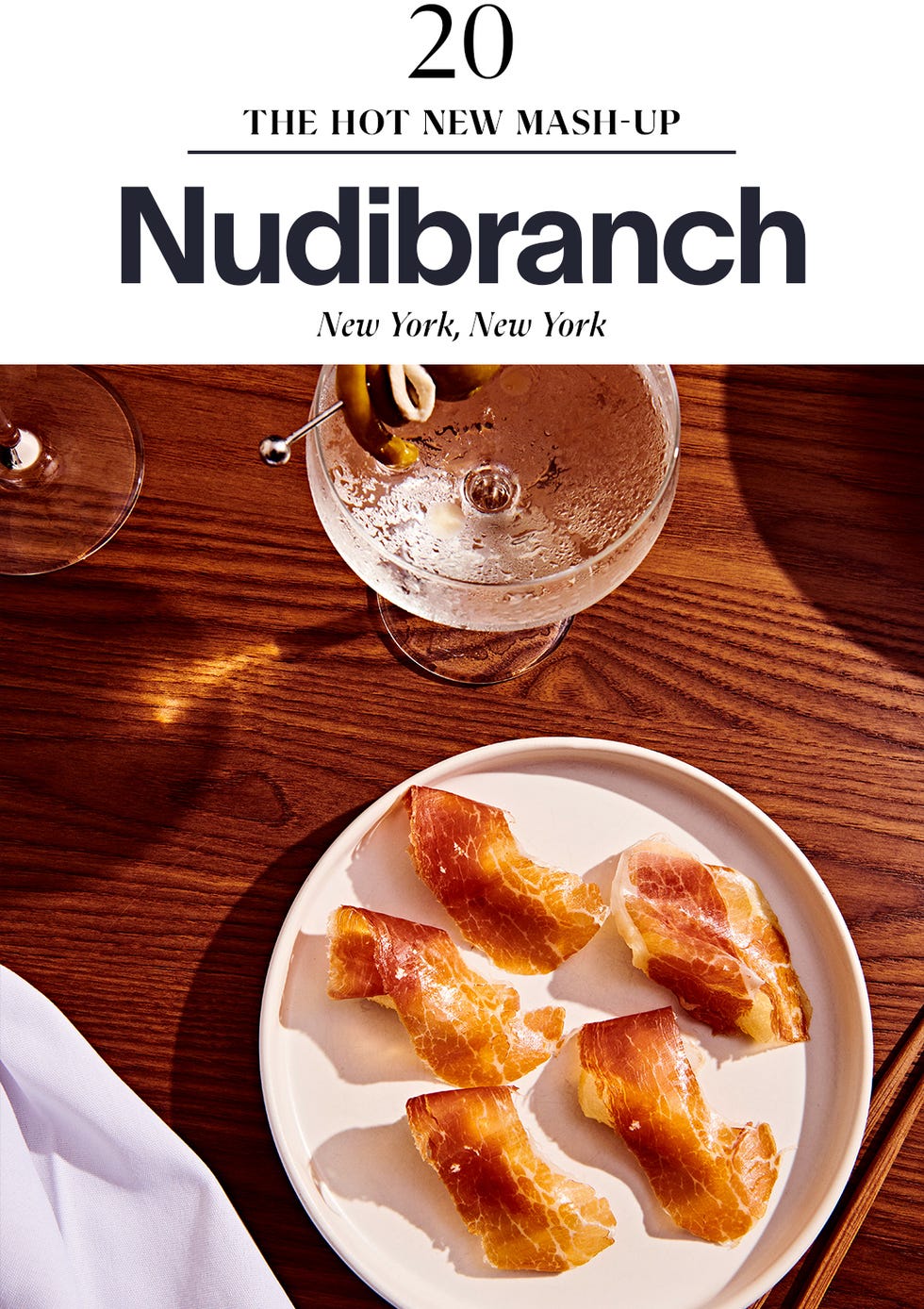

Nudibranch pulses with an energy that Manhattan’s East Village hasn’t seen since the Great Momofuku Moment in 2004: It’s a description-evading restaurant whose animating spirit appears to be “anything can happen.” Chefs Jeffrey Kim and Matthew Lee are in fact Momofuku veterans, but the cuisine they’re conjuring with their collective involves a mash-up of occasionally Korean foundations with everything from bottarga to aji panca peppers to Shaoxing wine to huitlacoche. You’ll find deep-fried frog legs and alpaca tartare; you’ll find country ham on rice cakes; you’ll find a martini garlanded with a gilda. Sometimes the combinations might be out-there, but when they click, the results are electrifying—even funny. This is a spot where the food didn’t just make me sigh with pleasure; it made me laugh along with the sheer chutzpah of it all. —J. G.

If you love restaurants, you live in restaurants. You fall in love in them, break up in them, catch up in them. This is especially true for the sort of restaurants we’ve covered over the past forty years. They are places where life hums through every morsel of food and plush banquette.

And then—they close. Many of the places in the previous thirty-nine editions of BNR are gone now. Nothing lasts forever. Not you. Not restaurants. When faced with impermanence, it is tempting to become a nihilist, but the more tender, truthful approach is to hold in one’s heart two things: the preciousness of the life lived within the four walls of restaurants and the knowledge that the experience and the space are fleeting. Do so and each meal will feel even more precious precisely because the wild constellation that is the restaurant is just a transitory arrangement. This verse from the eighth-century poet Sekito Kisen offers me comfort walking down blocks I hardly recognize, past restaurants long gone: “In the light there is darkness, but don’t take it as darkness; in the dark there is light, but don’t see it as light. Light and dark oppose one another, like the front and back foot in walking.” —J. D. S.

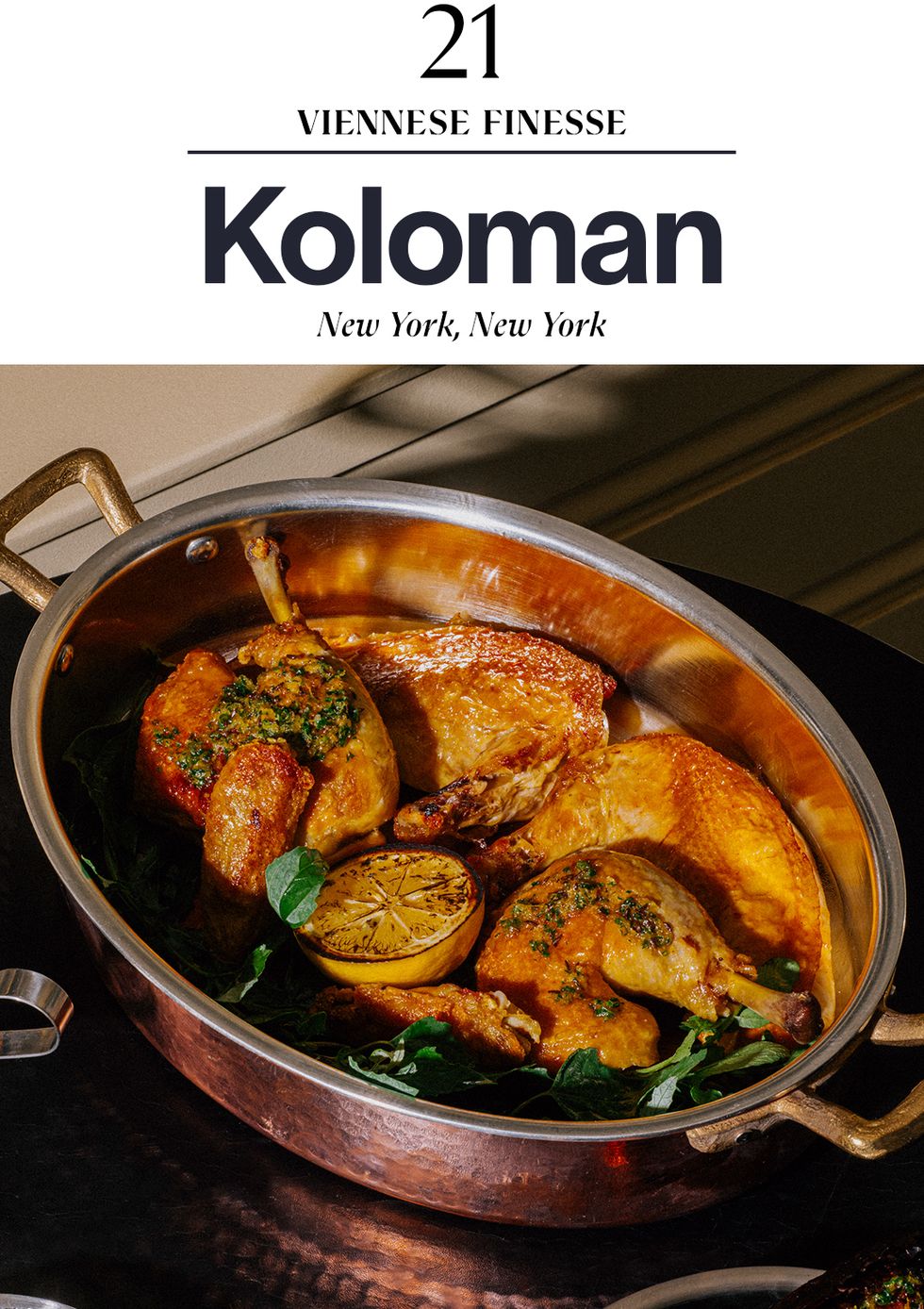

Take a bite of chef Markus Glocker’s salmon en croute — the crust both pillowy and crackling, the fish inside as soft as butter — and you realize you’re encountering a mode of old-school European technique that has moved, in recent years, to the margins of American dining. But don’t worry: Koloman is not a place where you primly sit and marvel at a virtuoso’s meticulous fretwork. Thanks to Glocker and his team, it’s a restaurant where you enthusiastically dig into rich, robust Franco-Austrian classics such as schnitzel, cheese soufflé, and a funky parfait of chicken liver under a delicate gelée. Glocker, like the late Eddie Van Halen, puts his meticulous methodology at the service of a single objective: throwing down.— J.G.

To nail the desserts at an Austrian/French restaurant is no mean feat, but Balthazar veteran Emiko Chisholm triumphs at Koloman with sweets that are both traditional (such as her spot-on sacher torte) and innovative (her crème brûlée incorporates mint, duck eggs, and caramelized pineapple). Yet Chisholm’s role at Koloman goes way beyond the sugary stuff: those are her fluffy and punchy gougères with Alpine cheese at the start of the meal, and that’s her pumpernickel accompanying the raw oysters, and it’s her cheese soufflé that everyone keeps swooning over on Instagram. Chef Markus Glocker would be the first one to tell you: Chisholm is Koloman’s ace in the hole. — JG

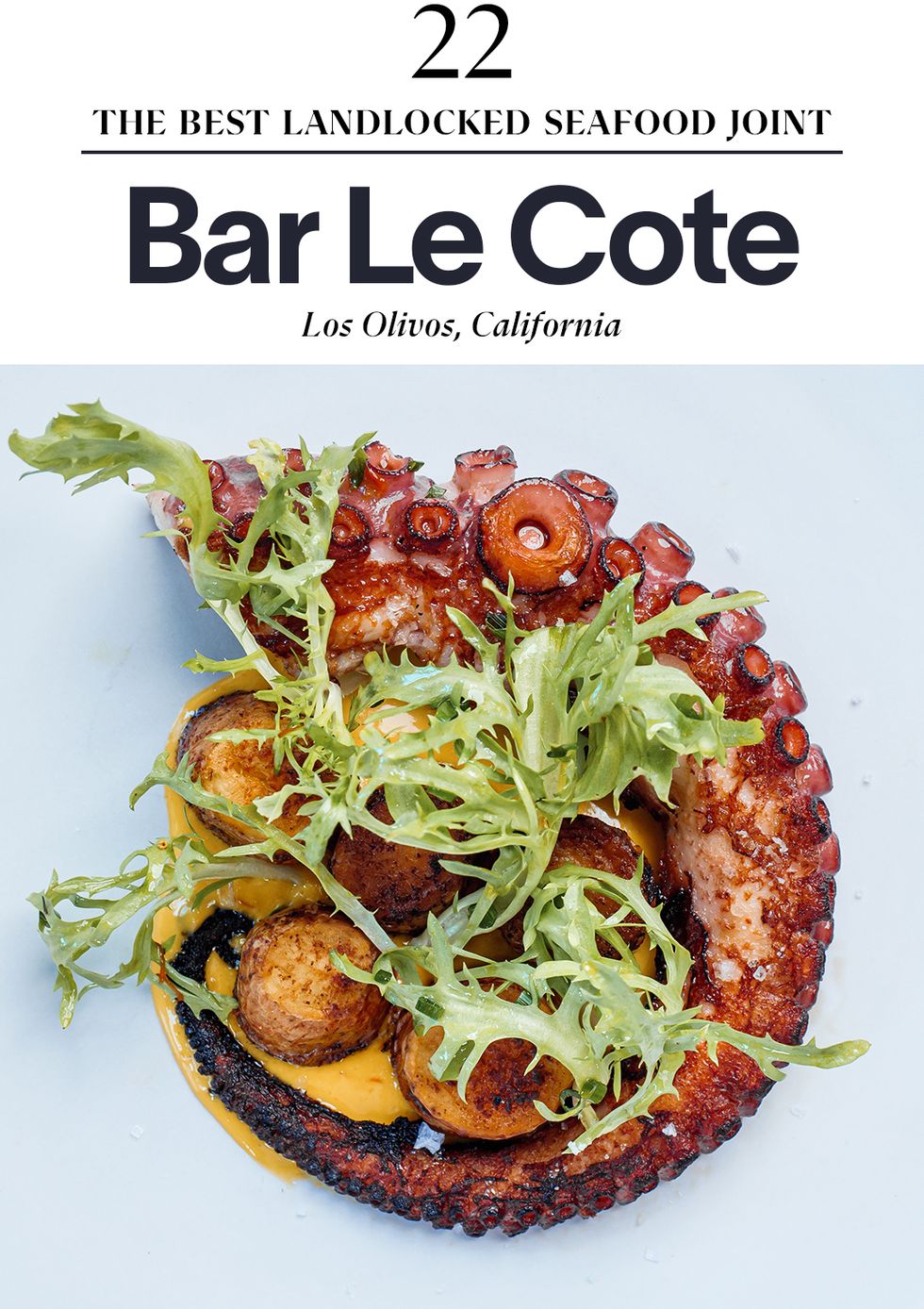

In a cute little town, on a cute little street that seems to pop up out of nowhere off California Highway 154, there is a place that exudes the kind of casual elegance you think you could only find from the Spanish or Portuguese coasts. But it turns out, if the kitchen plates day-boat scallops with pickled mushrooms, little neck clams tossed in house made chorizo, or perfect little white anchovies curled around olives and peppers, and a copious selection of easy breezy local wines are poured, you can conjure that seaside energy in the rolling hills of the Santa Ynez Valley. Co-owners Daisy and Greg Ryan were previously able to bring fun, unexpected French-ish cuisine with Bell's in nearby Los Alamos. A similar kind of transportation magic happens here with coastal cuisine from chef Brad Mathews and a wine program from Emily Blackman. If Bell’s was reason enough to drive the 45 minutes north of Santa Barbara or make the day trip from Los Angeles, Bar Le Cote will make you want to turn the adventure into a long weekend.—K.S.

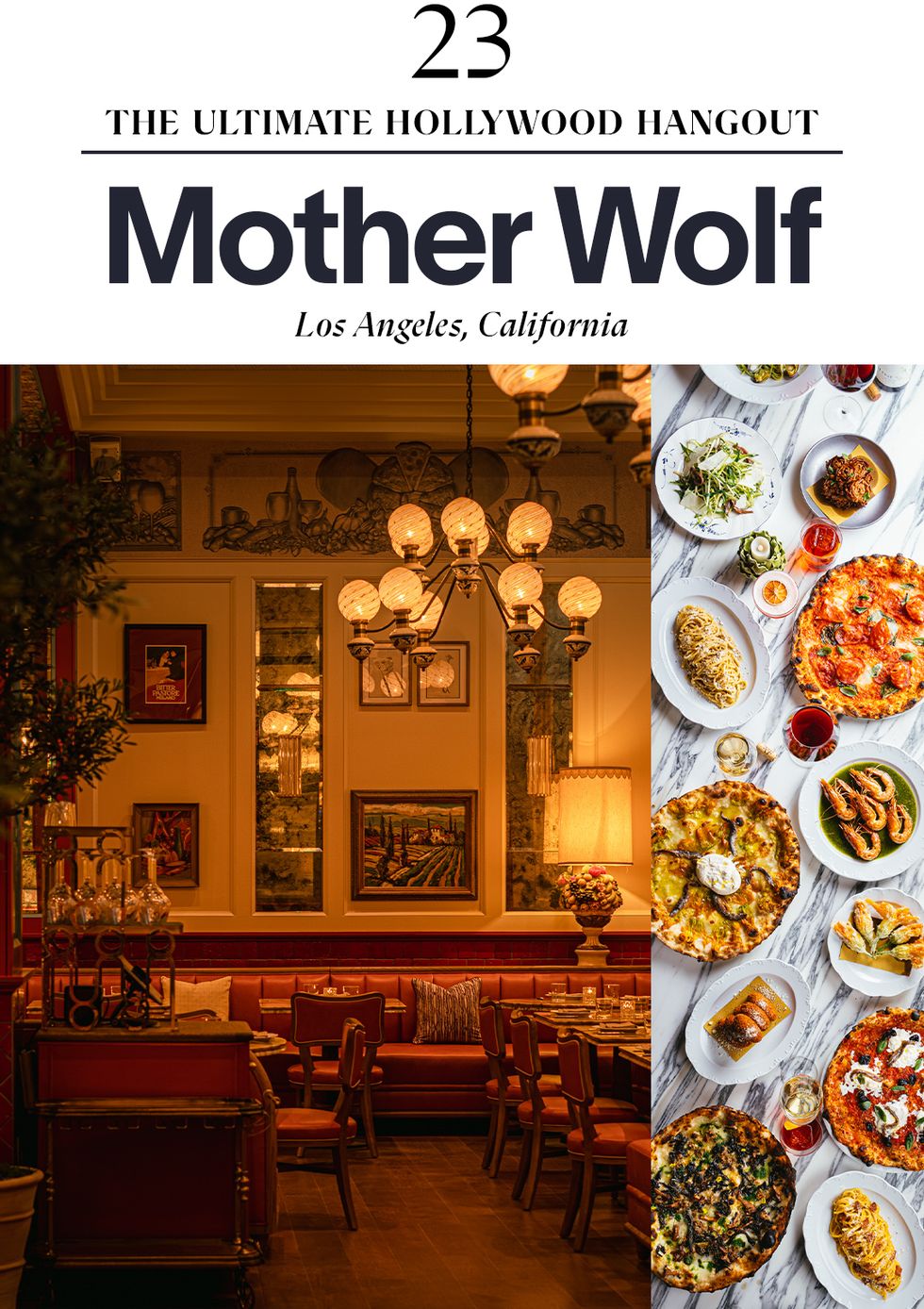

Notice the sound-stage-high ceilings, the trompe l’oeil scenes adorning the walls, the number of bold-faced names crowding into the pink booths with a negroni in hand. There’s a Rome-via-Hollywood (with a touch of Vegas showmanship) to the party that is Mother Wolf, chef Evan Funke’s big, bold homage to the food of the eternal city. The thumping drama of the place would be enough to get you to clamor for a seat at the bar. But as Funke showed at Felix in Venice (our top Best New Restaurant in 2017), he is a maestro with carbs. Before diving into the pizzas and the pastas, get the crisp squash blossoms and the oxtail meatballs. The delicate yet zingy gamberi In salsa verde might secretly be the best thing on the menu. But then you see a pizza that looks like a sandwich stuffed with mortadella go by and the server says “That’s the La Mortazza” and you say “La Mortazza, please!” And then you think, yep, this is the dish. But then a bowl of Rigatoni All’Amatriciana arrives, a harmony of rich guanciale and sweet pomodoro, a simple, quiet contrast to everything around you, and then you know: this is the reason I’m here.—K.S.

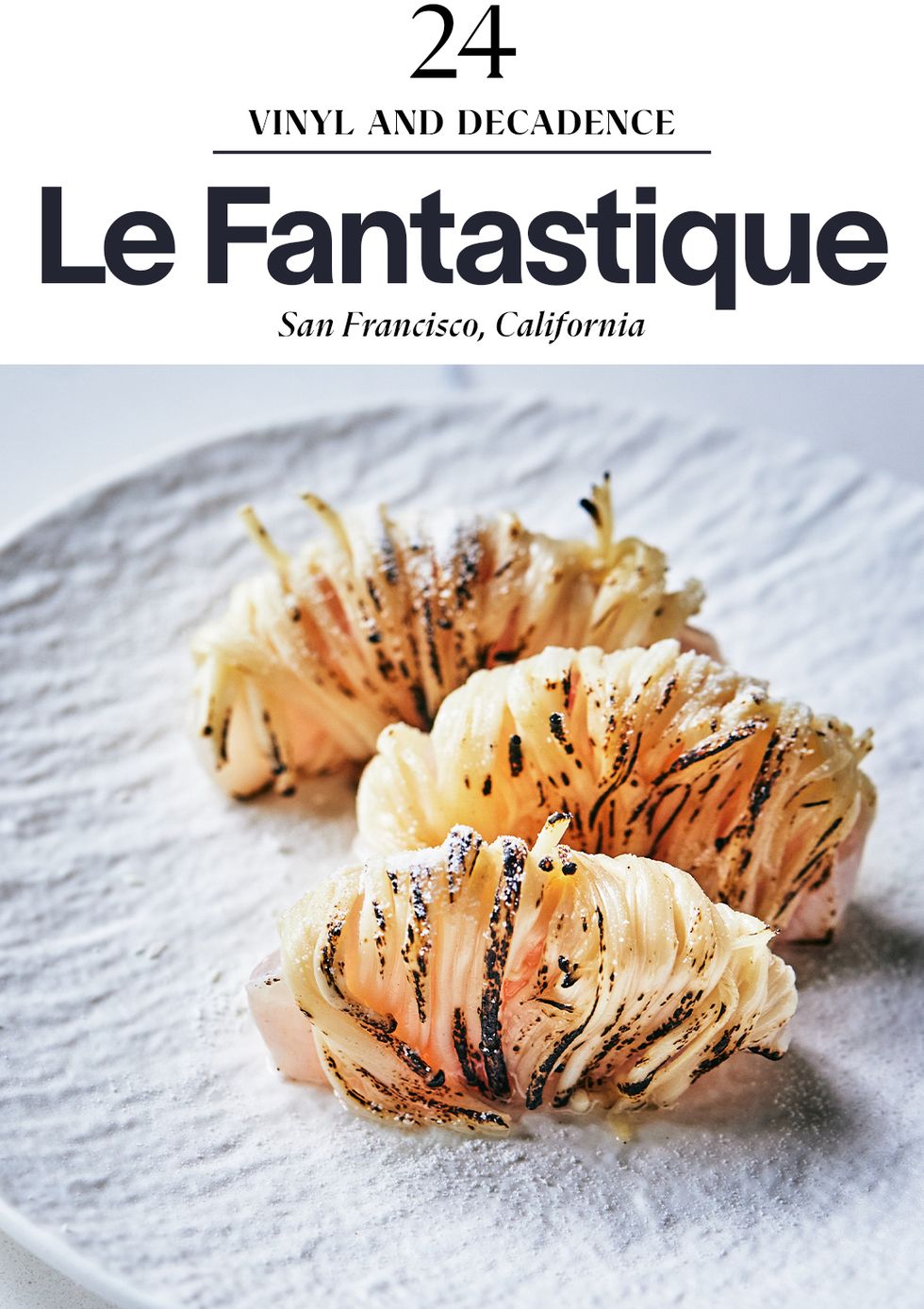

When it comes to caviar, I usually prefer simplicity in my delivery vessel. No blinis for me. It obliterates those briny little pearls. Just give me a thin, crisp potato chip, or, heck, dab a bump on the back of my hand. But then I came to Le Fantastique, where the caviar service comes with freshly baked brown butter madeleines and, well, I was convinced by this over-the-top decadence. I asked for more madeleines. The surprises at this chic joint, where vinyl records are casually played throughout the course of the evening on speakers powered by the warm glow of a McIntosh tube amp, are luxurious yet subtle. Chef Robbie Wilson has a deft hand with seafood: the scallops have the springiness of a gummy bear, the ocean trout is given zip through spicy espelette and sour orange. Most of the raw fish are brought into another dimension with artful aging. (Check out the glass-encased room in the back.) The biggest surprise might be the chicken breast, poached in creme fraiche, giving it a succulent, almost sashimi-like texture, and served with chicken skin cracklings. It’s all, well, pretty fantastic.—K.S.

Sometimes you’re looking for the hangout, that nexus of all the cool people and good local vibes that a city has to offer. And when your taxi weaves you through a quiet residential neighborhood to a tidy white brick building with folks buzzing outside the door with glasses of pet nat and orange wine, the radar goes off: yep, this is the hangout. A wine bar and restaurant owned by chef Tracy Malechek-Ezekiel and Arjav Ezekiel, Birdie’s is counter service, but don’t be put off by that–the business model allows for lower prices, a fairer wages for staff, and adds to the communal energy of the space. The lines are worth it for the food, a casual refined mix of American, a little Italian, a little French, that all makes you want to linger a little longer into the warm Austin night and order another bottle. (If they do their Aiello’s Italian pop up menu again, get the meatballs.) The vanilla soft serve, drizzled in olive oil, is non-negotiable.—K.S.

The list of bottles at Birdie’s has a way of transporting you with excitement throughout the world, and all of that energy comes through Arjav Ezekiel, who brings the kind of unabashed enthusiasm for wine in a way that only a self-taught oenophile could. With a generous amount of wines by the bottle that are in constant flux, every bottle on offer is a concise, tour de force of approachable yet thrilling low-intervention wines—nothing so off-the-wall strange that will have you thinking someone’s mislabeled kombucha as a sancerre. Like the food that comes out of chef Tracy Malechek-Exekiel’s tiny kitchen, the wine is serious, but the attitude is easy, fun, accessible, hospitable. The wines have one adjective descriptors: a Gamay is “haunting,” and a rosé, “jazz.” They are a succinct start to the journey in the sips ahead. K.S.

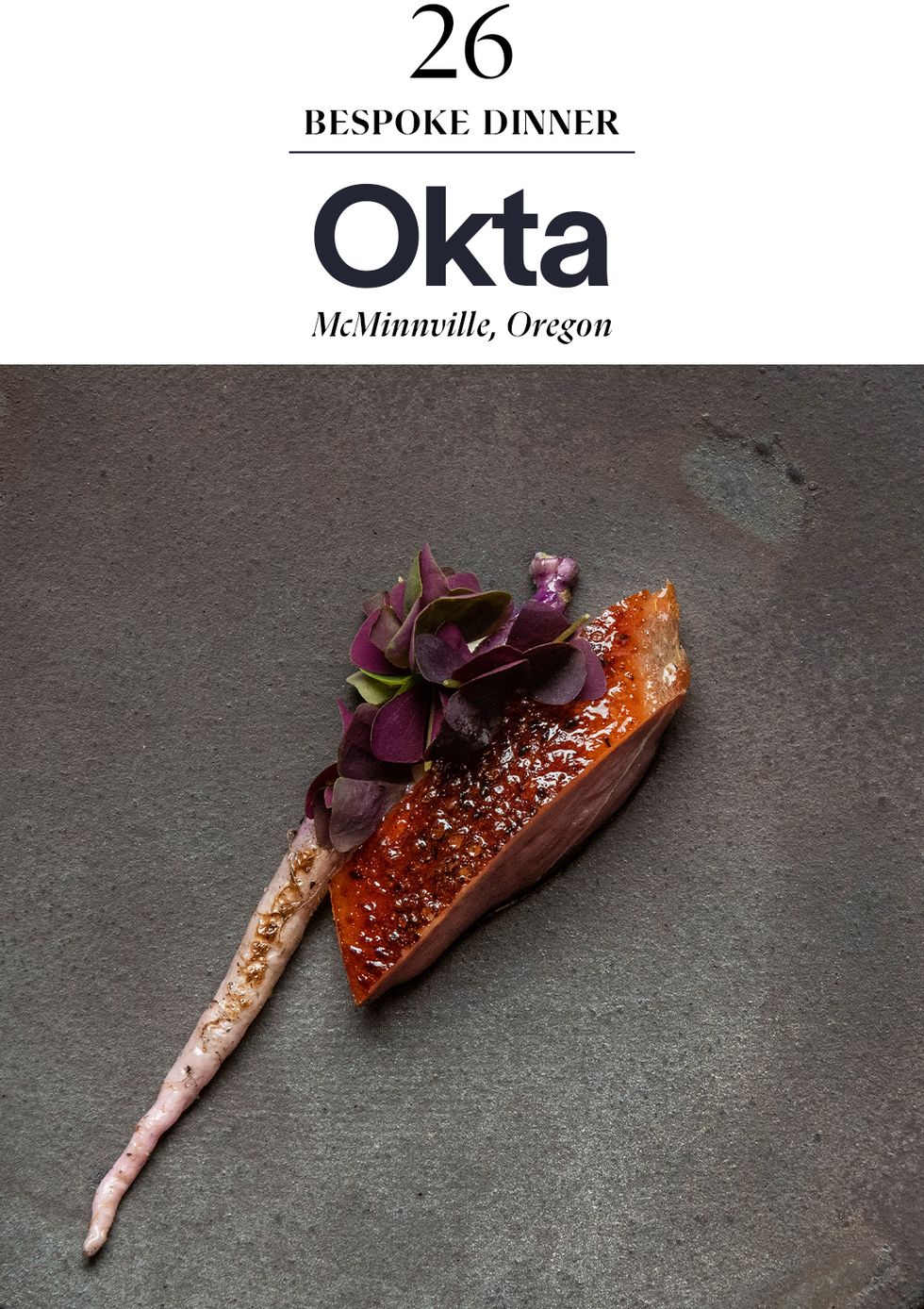

The heartbeat of okta, Matthew Lightner’s grand return to his native Pacific Northwest, isn’t the pulsating hearth in the back of the dining room or the focused action in the hushed kitchen or even the chatter and crystal chime of the parties dining. (The wine list, focused on Willammette Valley, is very good.) It is a few miles away at the five-acre farm that provides the raw material for Lightner’s efforts. It is not just a farm, but a larder, a fermentation lab, a bakery, a constantly shifting source of life. Like horse and rider, Lightner is so finely attuned to the seasons the two move as one. That means the tasting menu changes with the light and might include an egg custard, shimmering with corn; marinated albacore hiding, Salome-like, under a veil of cucumbers studded with dehydrated ground cherries; blueberries with an eggplant reduction topped with a Queen Anne’s Lace ice cream. That is, a wildflower turned into a far out flavor which, like the meal itself, is an argument for a close reading of the natural world. —J.D.S.

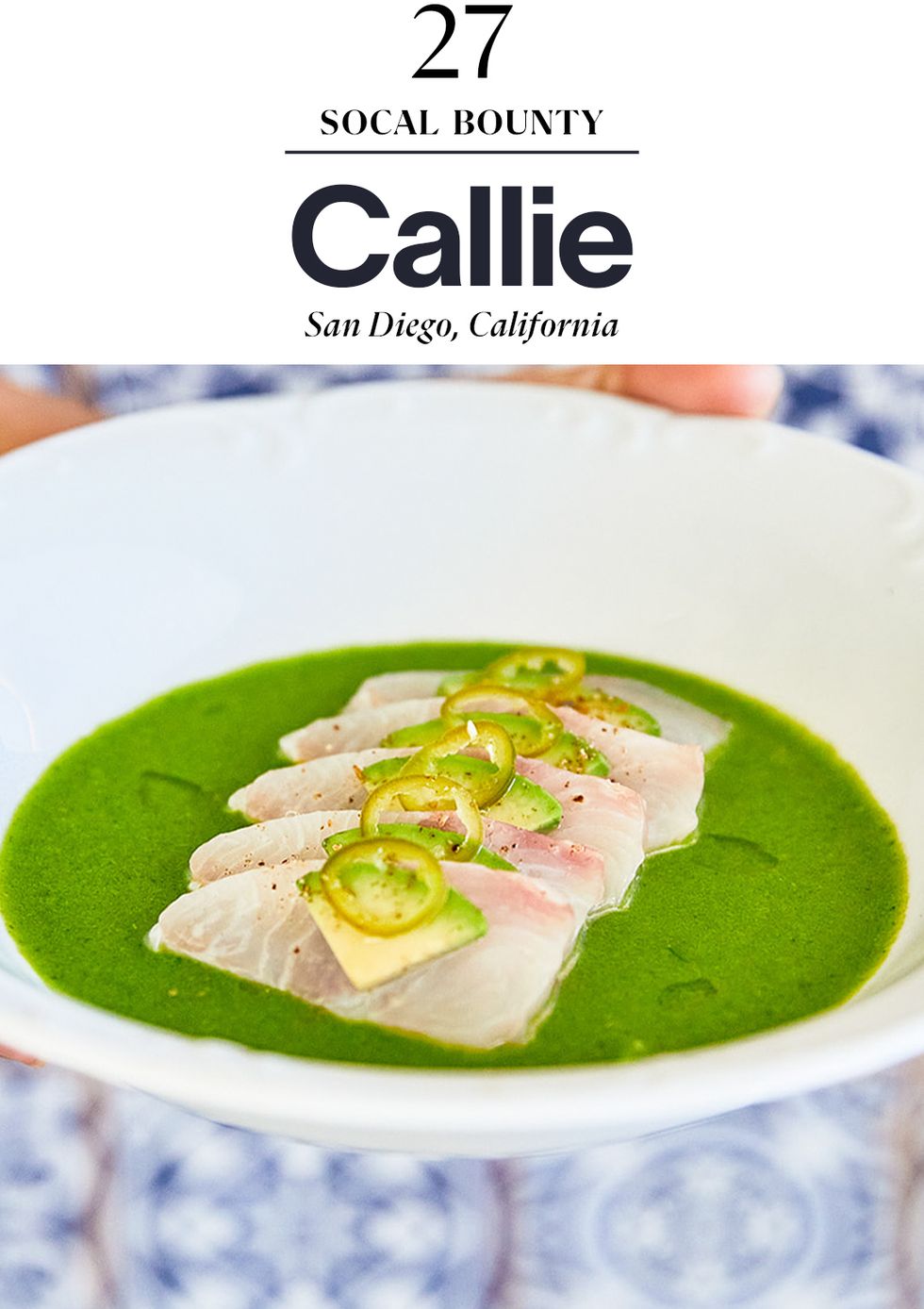

The nod is right there in the name. “Callie” may echo a Greek word for “most beautiful,” but it’s really a reference to California. Chef Travis Swikard and manager Ann Sim have opened a welcoming, commodious restaurant that exists to celebrate the bounty of the Golden State as much as the Mediterranean. Get whatever’s fresh (the phrase “spot prawns” should be your cue). Get whatever’s spreadable (Swikard’s avocado labneh with nigella seeds, pistachios, and crunchy raw vegetables is a West-Coast-meets-Middle-East marvel). And get whatever’s luxurious (we’re looking at you, uni toast with jamón Ibérico). Before moving home to San Diego to raise a family, Swikard spent years in New York in kitchens such as Boulud Sud; chef Daniel Boulud’s influence is clear, but with its bold embrace of citrus and spice and herbs, Swikard’s cooking also calls to mind the early days of Bobby Flay. Blandness and pretension are the enemies here. Chill out and eat with your hands — after all, you’re in Cali. — Jeff Gordinier

Esquire: What changes, good or bad, have you noticed in American restaurants over the past forty years?

Scott Conant: The overworking and endless hours we put in as young cooks—that seems to be changing, which is good. But the focus on getting better and the respect for the craft? That isn’t as intense as I remember it being.

Esquire: What changes still need to happen?

S. C.: Cultural changes are still needed. Too many egos and not enough heart.

Esquire: What’s a dish that you consistently order whenever you walk into a restaurant?

S. C.: No matter where I am or what I’ve eaten so far, I order a soufflé if I see it on a menu.

Esquire: What’s a dish that you’d happily never see again?

S. C.: Bad versions of classic Italian-American food break my heart.

Esquire: In your opinion, what’s the best American restaurant of the past forty years?

SC: Without a doubt, the French Laundry—and everything that Thomas Keller and his team have done for food in the United States. They are the American version of Hermès.

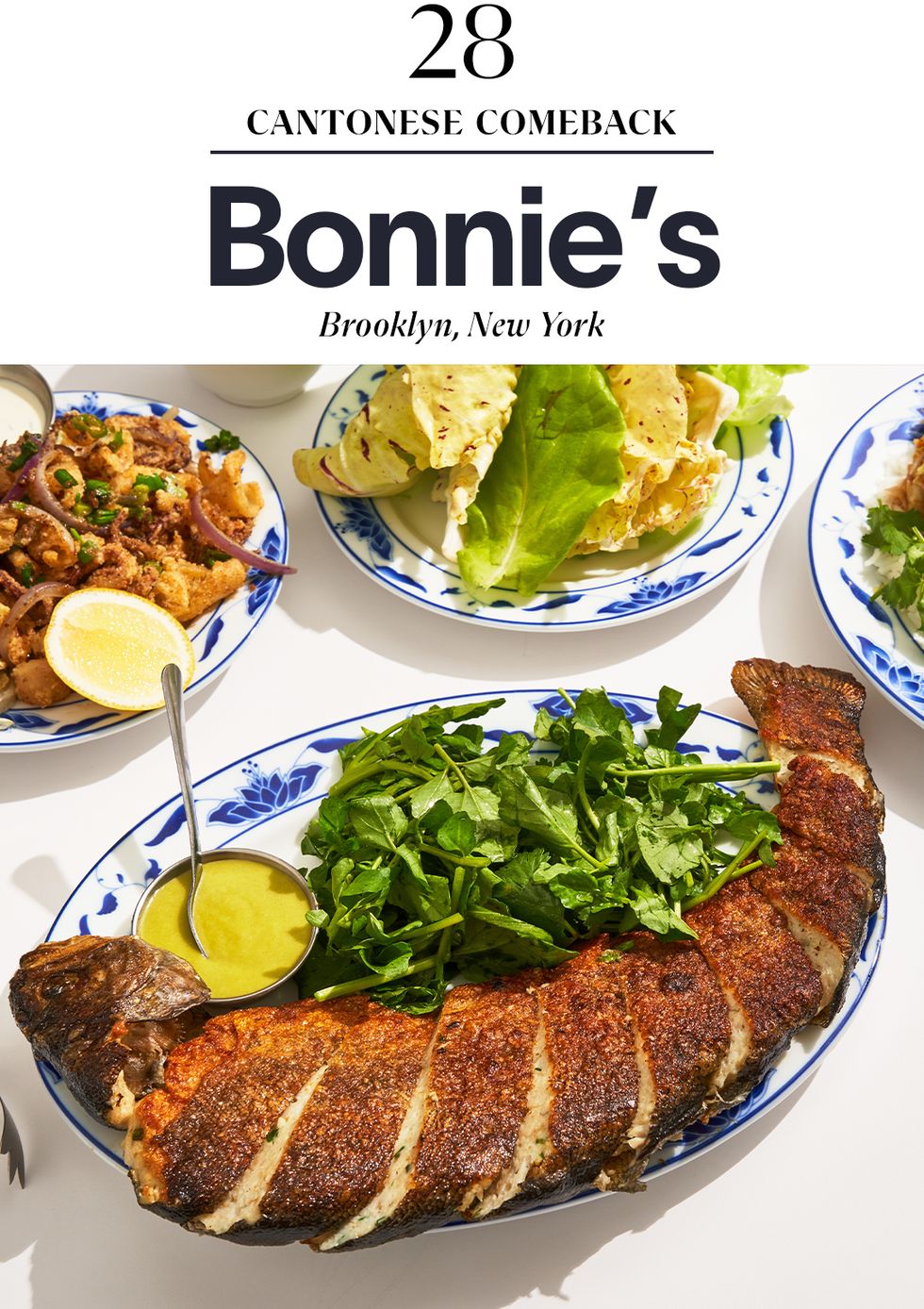

If you went to Bonnie’s and had the restaurant’s most talked-about dishes, you would leave a happy person. I wish I lived closer, and that there wasn’t a perpetual line out front so I could just pop in after work for an MSG martini (a bold take on the dirty), followed by perfectly handmade wontons in a broth fortified with Parmesan rinds, and the decadent cha siu McRib. That would be the life. But Bonnie’s is best experienced as a group so you can dive into the other mind-blowing comforts like Yeung Yu Sang Choi Bao, a whole trout that’s been deboned and then stuffed like a sausage held together with crispy skin, and the fuyu cacio e pepe mein, the classic Italian pasta given a deep swath of funk through fermented bean curd and a touch of smokiness from a toss in an ultra-hot wok. The place is an expression of Calvin Eng’s love letter to growing up Chinese American in Brooklyn. It’s personal and soulful, sure, but, most importantly, you just want to go back every week.—K.S.

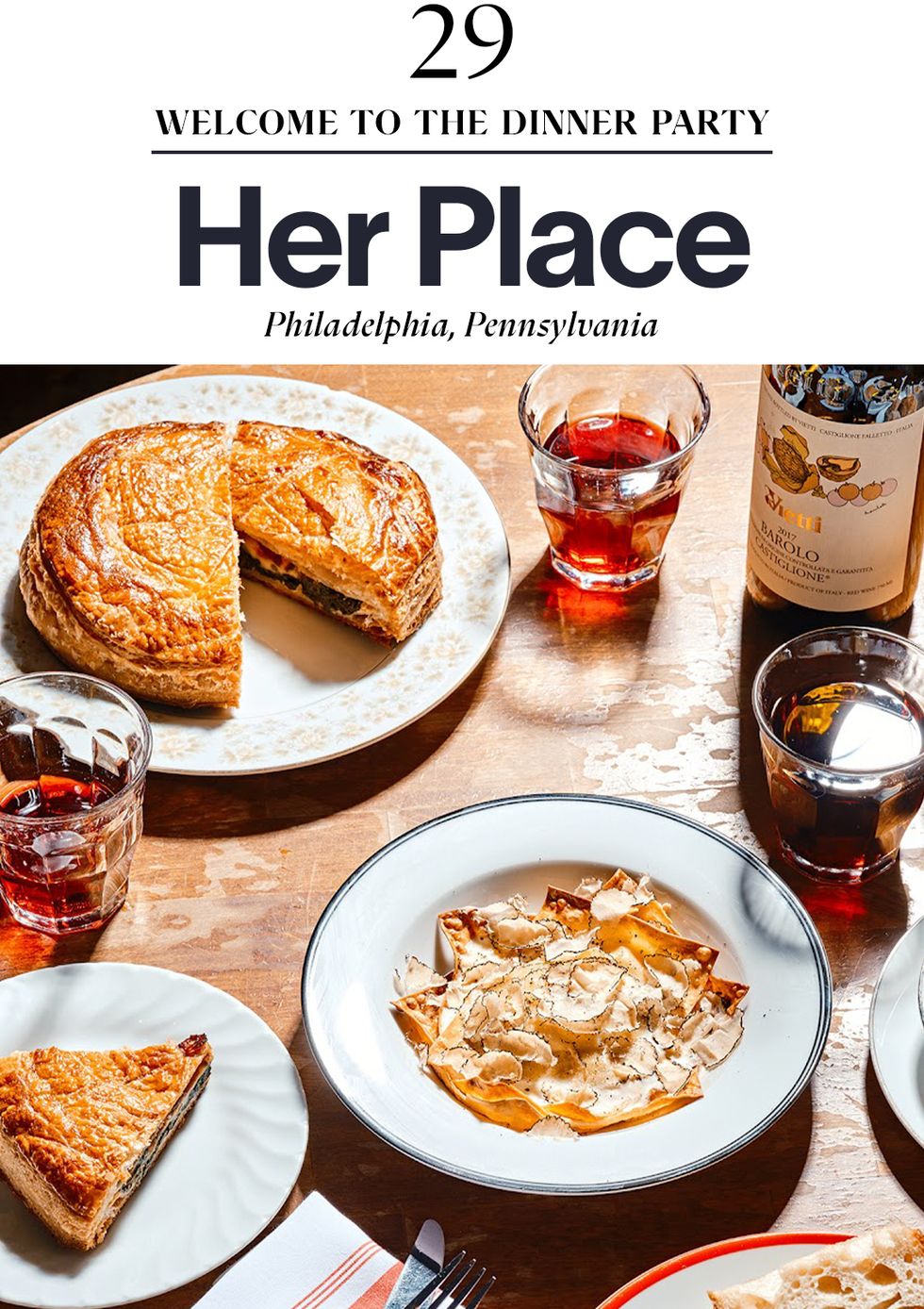

The warmth, as soon as you enter what was formerly a little pizza joint about a block away from Philadelphia's Rittenhouse Square, is infectiously welcoming. Are we all friends now? you might think. That’s because the idea of Her Place started from the dinner parties that chef Amanda Shulman used to throw in her apartment. The vibe is like you’ve come over to a friend’s house, but there’s no need to bring wine and the food is way better. At the beginning of the night, Shulman addresses the room and tells stories of the producers and purveyors from where your meal, a bargain at $75 for multiple courses, will be coming from. One week it could be stone fruit salad, marinated in a tomato vinaigrette; lobster toast with brioche soaked in a lobster mustard; pork and chicken liver terrine with a touch of sour cherries. At the end, Shulman comes around and presents guests with freshly baked cookies, a friendly gesture if there ever was one.—K.S.

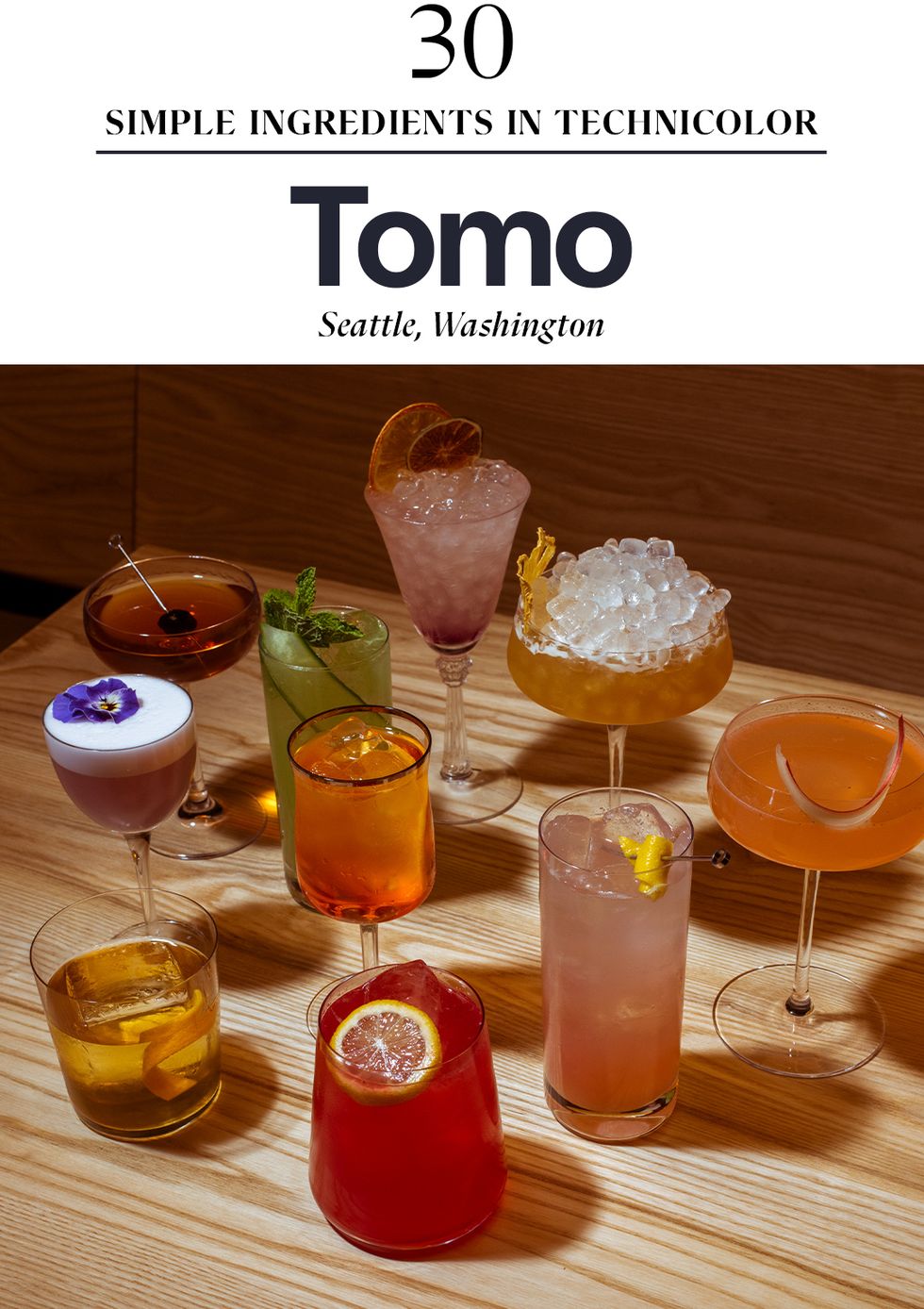

Tomo in Seattle’s White Center is quite the contrast to James Beard Award-winning Chef Brady Ishiwata Williams' Canlis past. The music is loud, the energy is high, and the dining room is lit—literally—with golden tubes of light that shine just right against the dark slatted walls. It’s almost as if you’re dining inside the Death Star, in the coolest way possible. The food he serves here is electric as the vibe: beef tartare tostadas topped spicy mustard green chiffonade and with ikura that explode in your mouth. Glazed lamb leg in a delicate yet powerful onion broth. Root-beer flavored kakigori the size of your head topped with punchy ling hi mui cream and decorated with plum pieces—it’s a necessary supplement and a refreshing finish to your meal.—O.M.

.

Esquire: What changes, good or bad, have you noticed in American restaurants over the past 40 years?

JJ Johnson: The best change I have seen is the impact of cultural food — what most people consider “low end,” but which is some of the most exciting food on the table.

Esquire: What changes still need to happen?

JJJ: Keep giving people of color a chance in positions that they have never been given a chance at before: general manager, executive chef, restaurant owners.

Esquire: What's a dish that you consistently order whenever you walk into a restaurant?

JJJ: Tuna tartare or a seafood tower. Also always looking for the oxtails.

Esquire: What's a dish that you'd happily never see again?

JJJ: Tripe.

Esquire: In your opinion, what's the best American restaurant of the past 40 years?

JJJ: The Cecil. I know I worked there, but consider the impact over the last ten years, from when the Cecil opened to now. The food of the African Diaspora has exploded across America, and that’s because of The Cecil.

Maria Rondeau and chef JuanMa Calderón’s restaurants have graced this list three times now over the years, but their places are just so undeniably joyful and delicious that we can’t help but continue spreading the word about them. If Celeste felt like an intimate dinner party, and Esmeralda was like a bbq for friends, La Royal is like the house party where you ask to bring your friends, too. The space, just a few blocks from their home, is warm, clean and inviting (Maria is an architect.) The food, dives deep into rustic Peruvian cooking, the classic stir fried sirloin dish of lomo saltado is given a deeper dimension with perfectly fried yuca, the pillowy causas, a kind of potato terrine, is dressed with avocado and tomato: it will make you angry at all of the mashed potatoes you’ve ever had.—K.S.

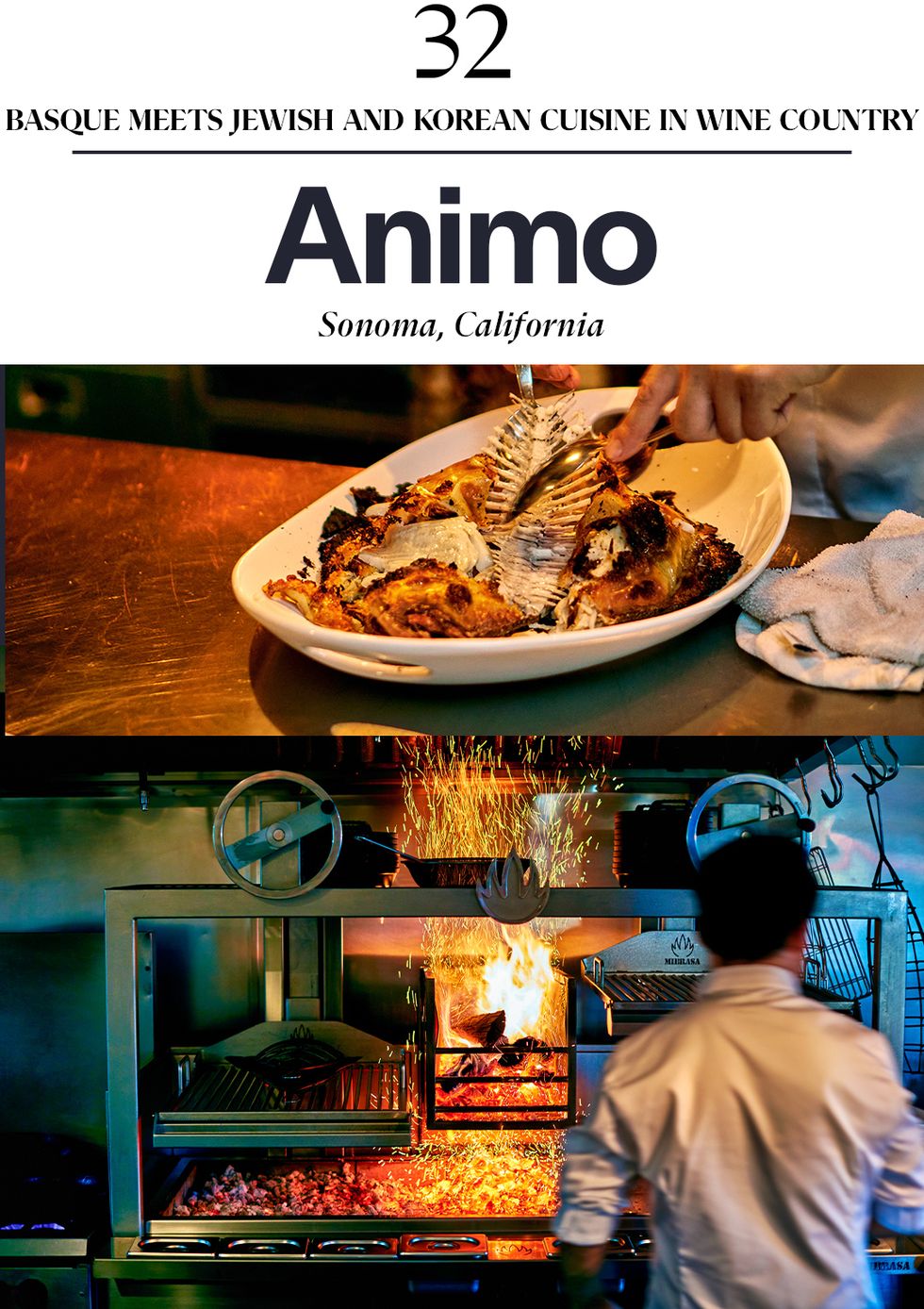

You just finished a long day of sipping and tasting through Sonoma’s Wine Country, and now you’ve got a major case of the hungries. Head straight to Animo, an unsuspectingly charming restaurant hidden in a former taqueria nestled between a McDonald’s and an auto repair shop. Inside, you’ll find Chef Joshua Smookler creating inventive Korean-Basque fare like nobody’s business. Born in Korea and raised in New York (the rows of apple art that line the wall and Katz’s pastrami-studded fried rice serve as subtle nods to his background), you’re here for the turbot, which Smookler imports from Spain and dry-ages for before gently grilling over burning almond wood, just like at Elkano in Spain (if you know you know). Every bite is different: tear at the skin, crisp as glass, bite the bones, full of gelatinous goodness, and mop up the tender flesh in the garlicky pil pil sauce. Go ahead, use your hands—they’re the best utensils.—O.M.

Though it may be true that Eleven Madison Park is the performative Xanadu of a mad man, it is also one hell of a talent incubator. Before he moved to Maine – his wife, Selena, is a Mainer -- Colin Wyatt was the executive sous there. Now he’s one upped EMP at Twelve, located in a reconstituted 150-year old brick storehouse at the water’s edge in Portland, ME. The technique is still there -- Wyatt makes particularly good use of ferments and yeast -- but Maine is the focus and there’s a New England modesty that prefers showing to telling. There are only twelve items on the prix fixe but Wyatt makes good use of his new home. The state shows up in the colors. The bright orange of sweet potato Parker house rolls mimic the foliage; the pumpkin-sdeed butter that accompanies them recalls the fields. And goddamn if his soigne lobster roll -- an entire half lobster impossibly folded into a small very buttery laminated dough -- doesn’t turn the volume of the old Maine banger up to twelve.—J.D.S.

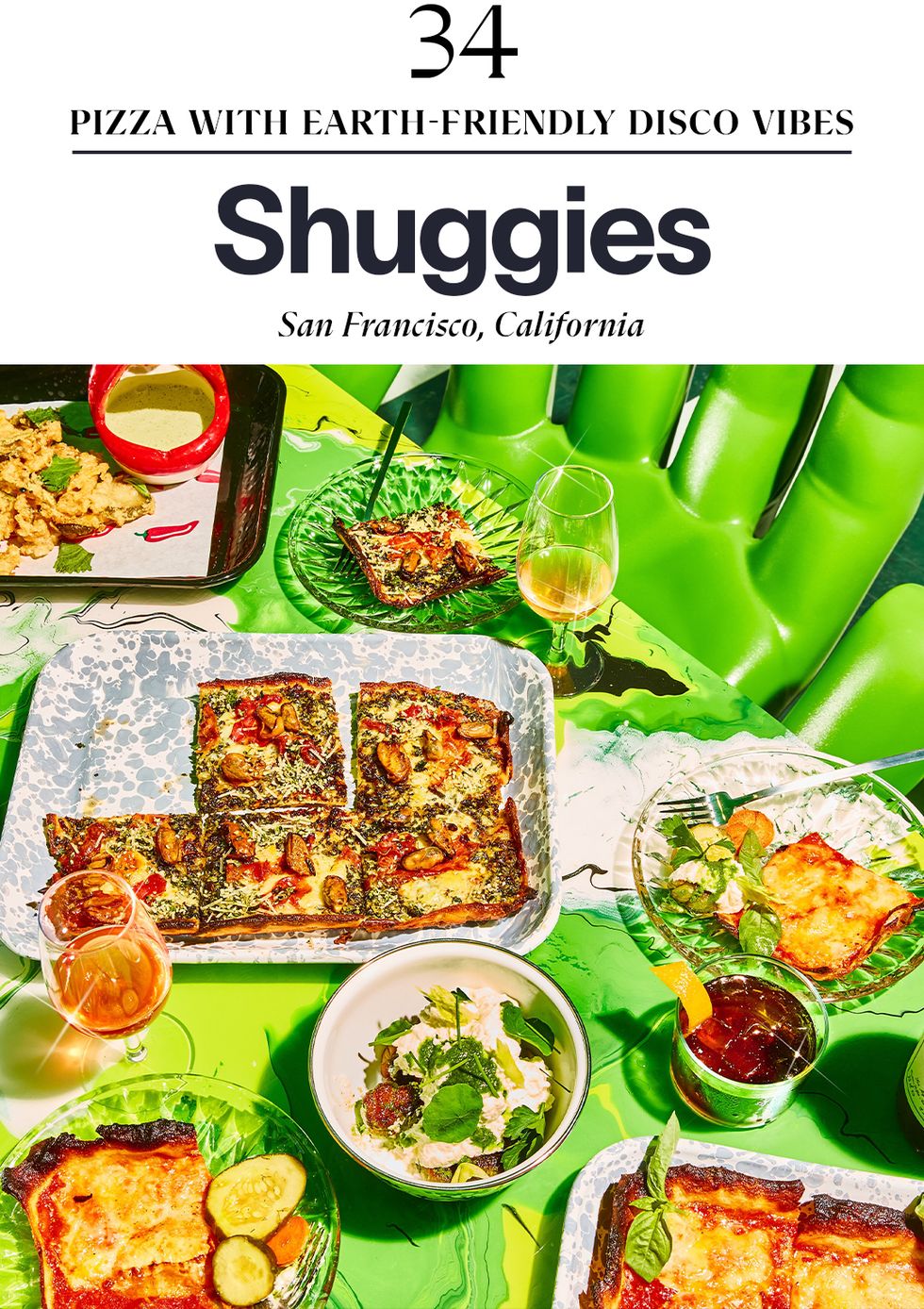

Stepping into Shuggie’s feels like you’ve entered a colorful and chaotic psychedelic maximalist dreamscape—in the best way possible, of course. The front room is painted entirely bright yellow floor-to-ceiling, the couches are shaped like lips, cartoon tigers and snakes decorate the walls, and an English bulldog named Beef greets you behind the glittery green bar in the back, ready to take your order (or be pet on the head, at least). But there’s a mission to the menu by partners Kayla Abe and Chef David Murphy: to use upcycled ingredients in their dishes—things that would other be thrown away like misshapen produce, off-cuts, and bycatch--and turn them into climate-friendly deliciousness in the form of pizza and small plates. Their pizza—more like a flatbread—is thin, square, and crispy, topped with things like sunburned squash, ugly mushrooms, and abandoned chard. Don’t snooze on the fluffy garlic knots, which is made from leftover dough and topped with airy creamy rich whipped ricotta and chimichurri made from wilty greens, herbs and leaves.—O.M.

Esquire: What changes, good or bad, have you noticed in American restaurants over the past 40 years?

Missy Robbins: Anything goes! You can be super-fine dining or make wood-fired pizza — and have equal status. You no longer need to cook fancy food or use expensive ingredients to be considered a great chef or restaurant. That way of thinking has opened the door to more diversity in cuisine and the opportunity to eat special meals in more relaxed dining rooms.

Esquire: What changes still need to happen?

MR: Still more diversity in cuisine — and celebrating different cultures in restaurants. What Roni Mazumdar and Chintan Pandya have done for their cuisine in the last few years with Dhamaka, et cetera — it’s incredible. More of that.

Esquire: What's a dish that you consistently order whenever you walk into a restaurant?

MR: Anything with sardines or anchovies. (I like oily little fish.)

Esquire: What's a dish that you'd happily never see again?

MR: My mom always told me if I don’t have something nice to say, don’t say anything at all. That being said, please don’t sous-vide a chicken, then sear it, and then call it a roasted chicken!

Esquire: In your opinion, what's the best American restaurant of the past 40 years?

MR: I have only eaten there two times but I think about my meals at Chi Spacca in Los Angeles frequently.

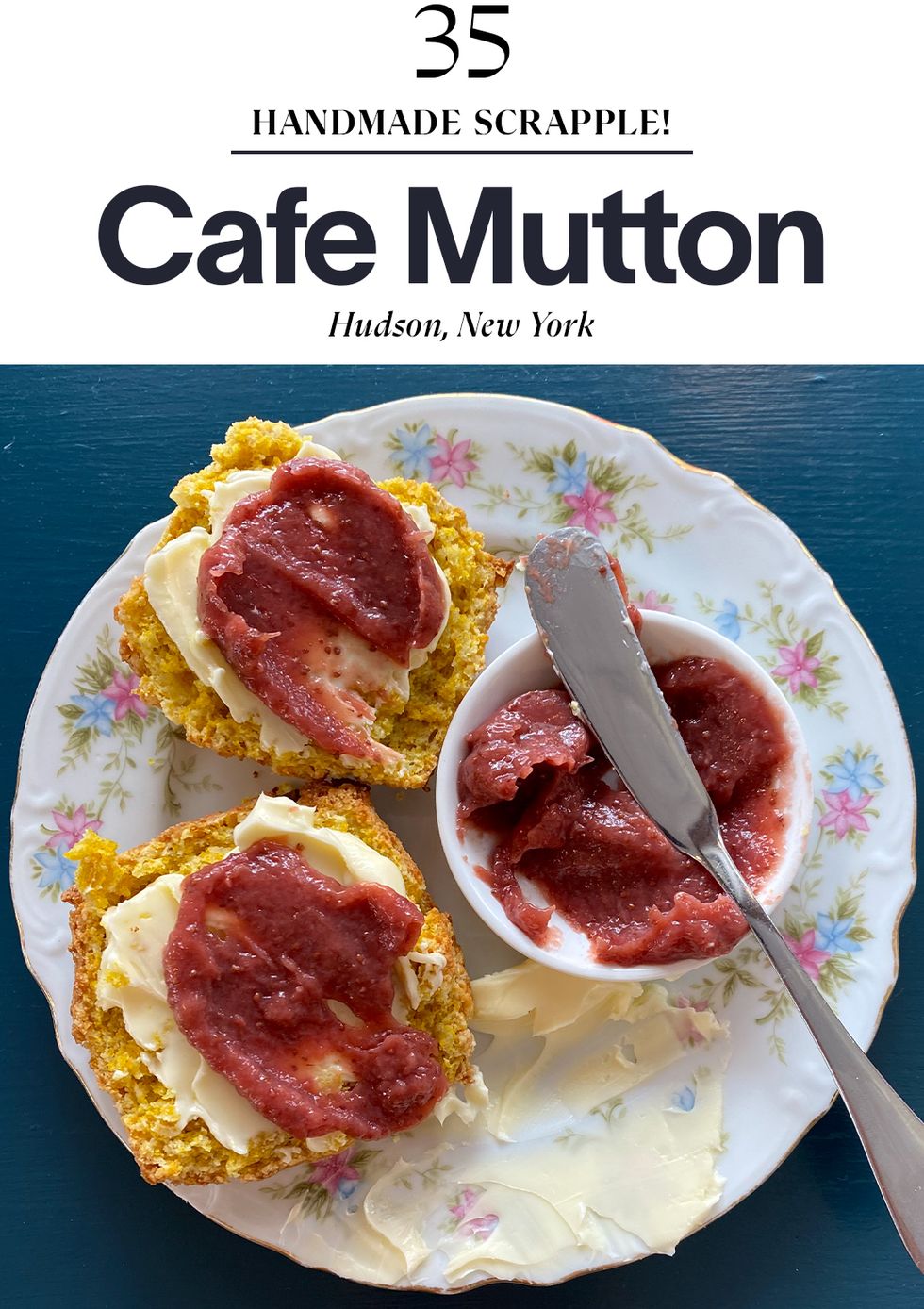

Great restaurants know what they’re doing — and what they’re saying. They open with a viewpoint that’s pretty much unshakeable because the team in the kitchen is cooking what they’d want to eat if they happened to wander into the same place. (No substitutions!) Cafe Mutton is a prime example. It’s a wonderful oddball refuge on an off-the-beaten-path Hudson Valley corner with a chef (Shaina Loew-Banayan) and a team who are wholeheartedly committed to the funky, fatty, oily, grainy, even gnarly pleasures of scrapple and bluefish and pig trotters and headcheese and fried bologna sandwiches. This is no-frills grandma food as interpreted through a 21st-century queer lens, and while the hospitality vibe makes a point of making everyone feel welcome, we’re not in the Kansas of “the customer is always right” anymore. Case in point? Mutton is open for dinner only one night each week. — J.G.

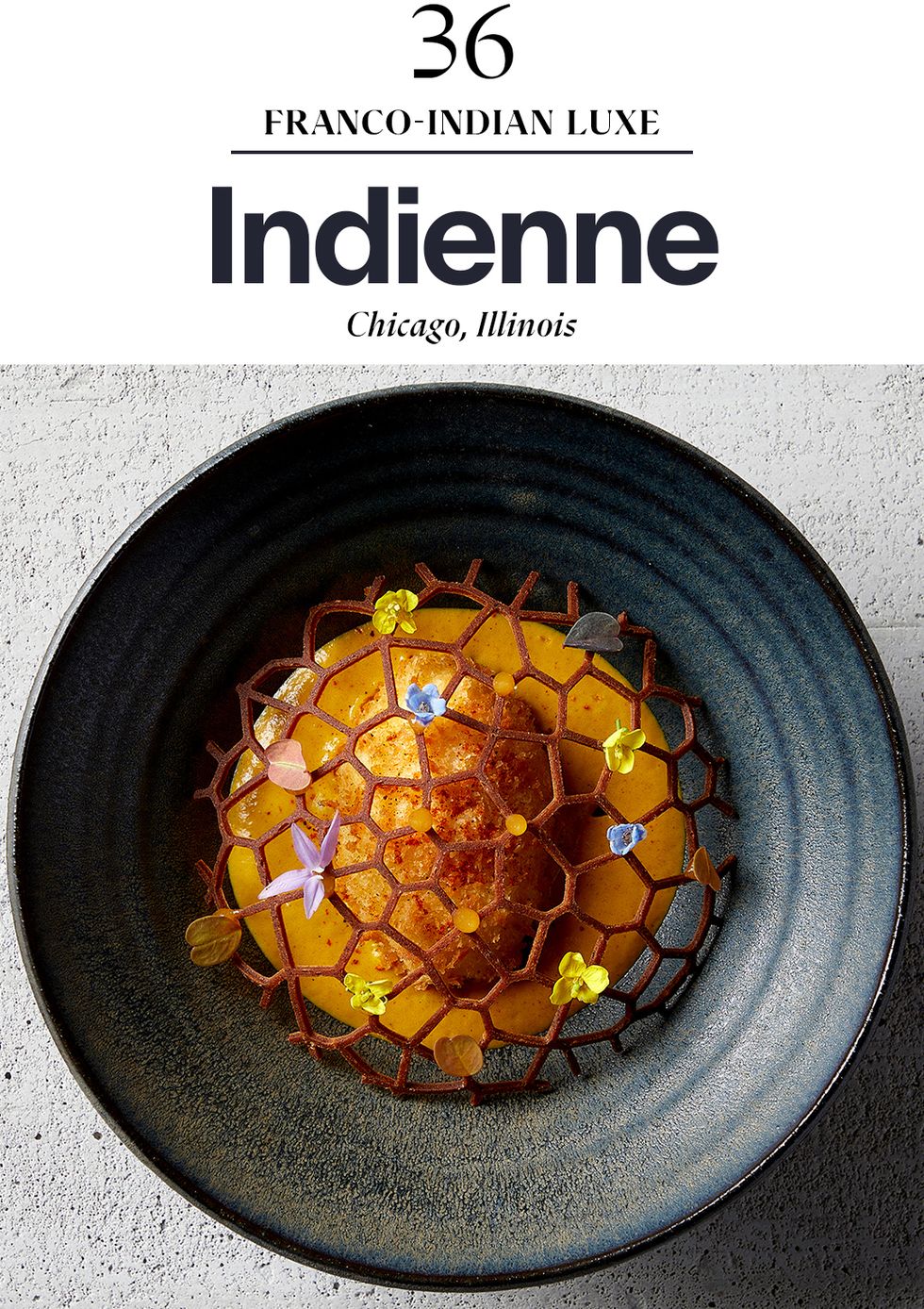

In a city where you could build the most credit-card busting culinary vacations around high-end tasting menus outside of San Sebastian, Indienne’s is a steal at $90. The service is delightful, informative, proper, the room is vast and luxurious, the wine pairings are illuminating. You might be wondering, what’s the catch? As far as I can tell, there is none. While French-techniques applied to Indian cuisine (or any cuisine) is nothing new, that combination here is from chef Sujan Sarkar, is potent and unexpected. The galouti, an Indian kebab traditionally made with lamb is transformed into an eclair with foie gras and chicken liver and an inviting spice. The malai tikka is served not as a skewer, but as a terrine topped with truffles for good measure. The cocktails, from Chetan Gangan Maverick, go beyond the Indian twist on a classic model to deliver something out there delicious–if you don’t think mezcal, goat cheese and apricot would work in a drink, the Delhi cocktail will prove you wrong.—K.S.

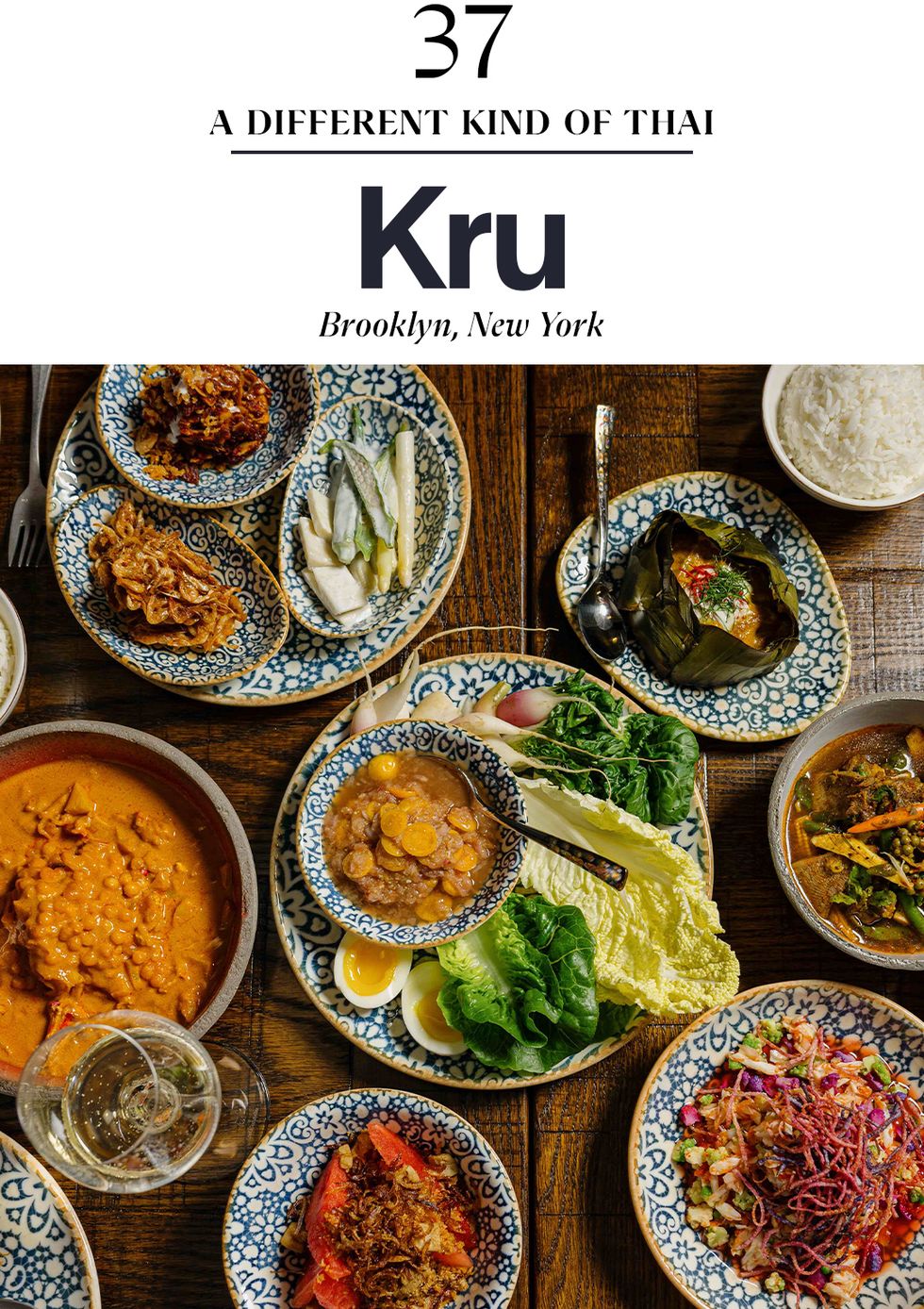

Thai restaurants have been around long enough in America that there’s a wave of them that dive into different regions of the cuisine, in addition to more personal, nuanced takes. Kru, which roughly translates to a cross between teacher and mentor in the Thai language, is a mix of both. The husband-and-wife team of Chef Ohm Suansilphong and Kiki Supap have dreamed up a menu of takes on forgotten recipes found in books that documented various family recipes, including some which were only served at Thailand’s Royal Palace decades ago. It all adds up to an unexpected menu of none of the usual suspects. The most surprising items are the relishes and dips served with fresh vegetables crudite style: you’ll want to have a group to order all of them, but if you only have room for a few, get the nam prik made with Thai chili, galangal, and dried shrimp, and the cured pork jowel relish which comes with a sidecar of deep-fried house cured fish. Should you be up for it, the “Kaeng Pa” Beef Tongue will have you crying from intense heat and joy.—K.S.

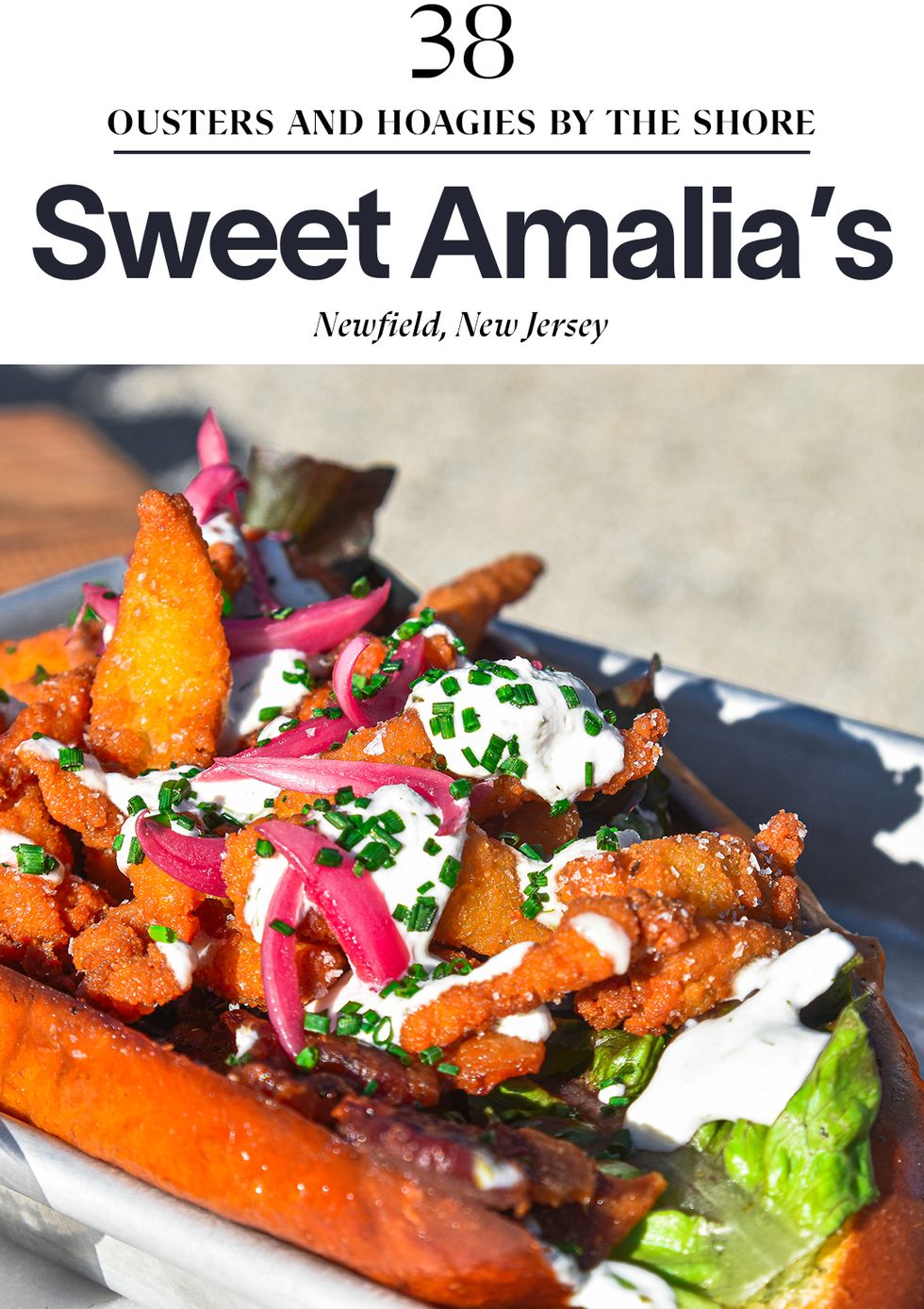

On one of those long highways in southern New Jersey where there’s still farmland among the random standalone buildings that have yet to become strip malls, there is an unassuming stand on the way to the shore. It looks like a charming little market, and you can stock up on gourmet olive oils and the like. But you’re here for the oysters and the hoagies. Take your pick of sandwiches. Get a dozen of the namesake Sweet Amalia’s which come from north Cape May, grab a beer from the fridge, and find a seat at one of the shaded picnic tables outside. Slurp those oysters slowly. Appreciate how they are pristine, yet wild and buttery and, yes, sweet and maybe like nothing you’ve had before. By the time you’re done, that hoagie you ordered will have arrived. (Did you choose the fried clam roll dressed with bacon or the garlic roast pork shoulder and broccoli rabe numbers?) We were already familiar with chef Melissa McGrath’s magical sandwiches from San Francisco’s Palm City (a Best New Restaurant from 2020) and they are just as crave-inducing here. Whether you are coming or going to the shore, you can’t resist taking another for the road.—K.S.

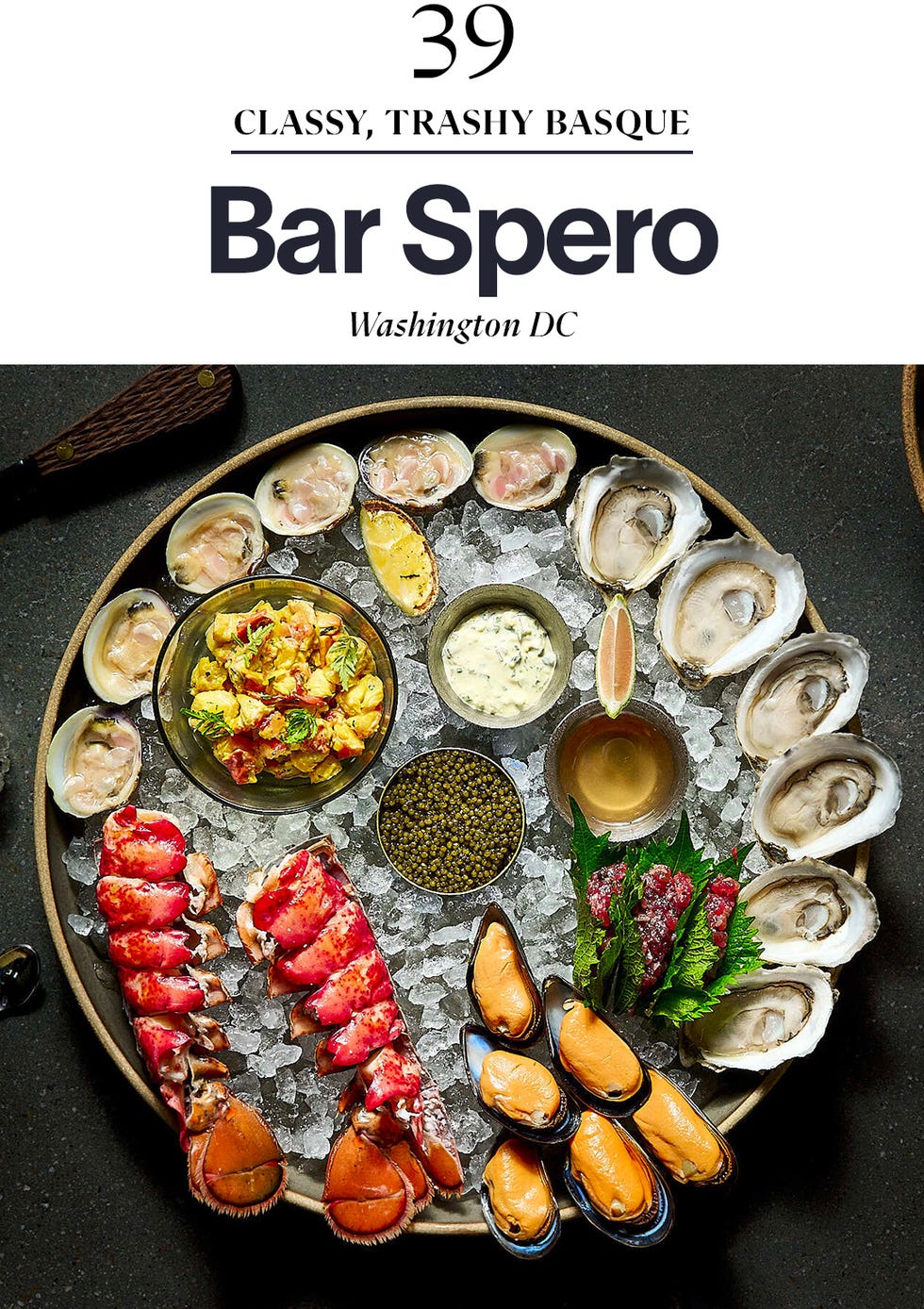

When my friend and I ordered the very last uni special of the evening—it was an entire tray of glistening hokkaido uni served with a French omelet, glazed in dashi butter and topped with roe—Chef Johnny Spero delivered it himself and was almost apologetic for offering such an outrageously over-the-top dish as a special. “It’s classy, but trashy,” he said, before returning to the kitchen to mind the blazing hearth. In other words, Bar Spero does not take itself too seriously, but the cooking is pretty damn serious—and fun. Sunchokes are served with Virginia peanut praline . There is a beef tartare made of cornichons, capers, and a smokey beef fat lending it a lovely ‘Nduja like consistency–it’s artfully crowned with thin strands of potatoes dusted in green allium powder; and there are dishes that are expressions of Spero’s time in Basque country where he learned, sometimes you just have to let quality ingredients sing: baby squid is gently cooked over the flame and served in an inky sauce. They were the night's most perfect bites. Turns out Bar Spero’s understatements can be pretty loud too. —K.S.

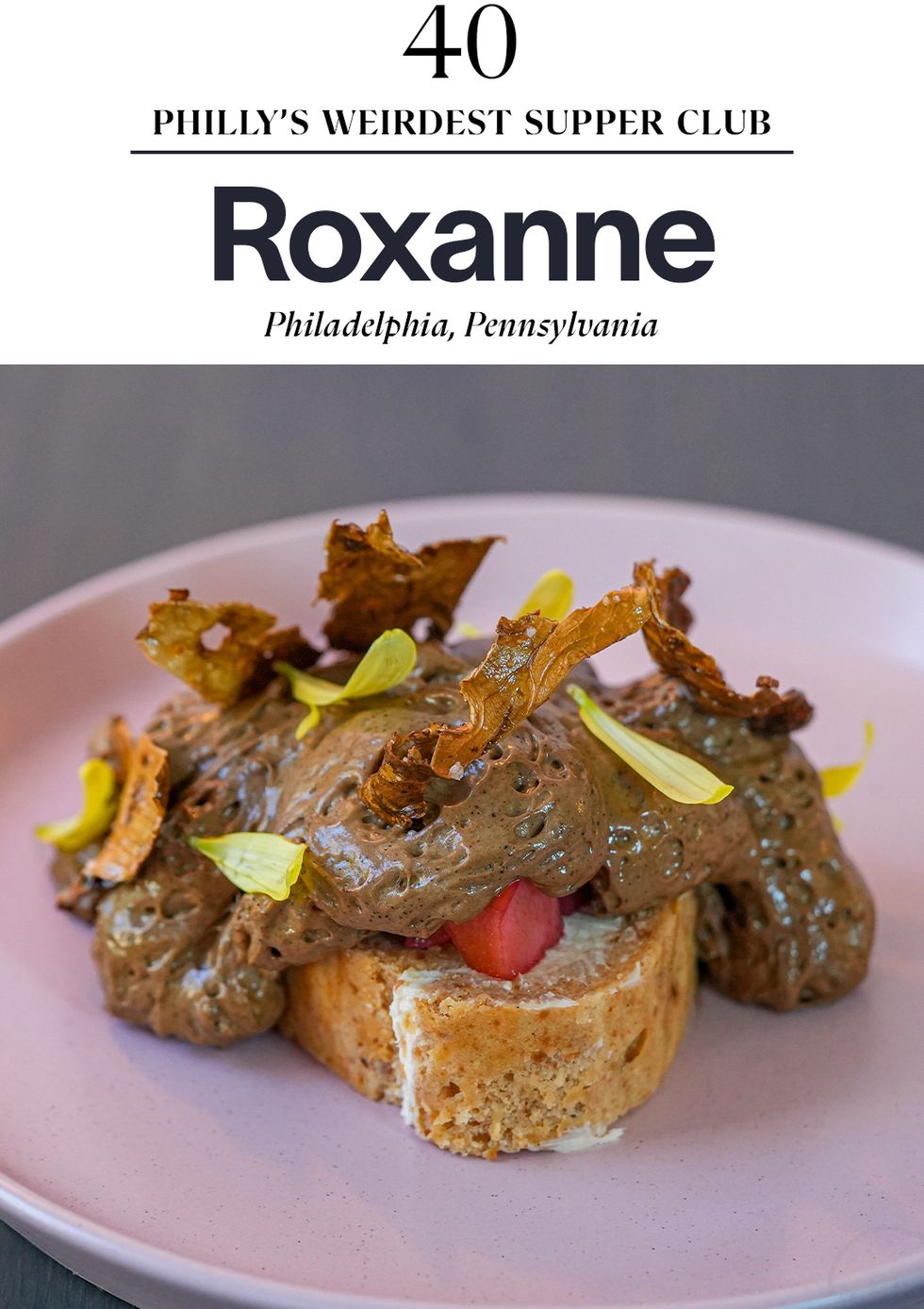

The first dish was honeynut squash, covered with a slice of salami cotto. It was decorated with a smiley face. It was kind of perfect that my dining companion at Roxanne, a funky purple-walled dining room on the first floor of a South Philly rowhouse, was my ten year old daughter. There’s a playfulness to Chef Alexandra Holt’s BYOB, six course, $75 tasting menu that she pulls together all on her own. The dishes are almost like late night munchies manifested as culinary fever dreams. The tongue and cheek tartine is smothered in an amalgamation of finer cheeses meant to taste like good ol’ American cheese. Spicy mapo sauce is served with mussels, atop potato puree . You can have the option to toss caviar on top of a sundae that is already maxed out with pineapple jam and black olive caramel, because, dude, there are no rules here. Roxanne’s feels like you’ve stumbled upon a joyful experiment where there’s raw, vibrating talent behind all the whimsy. My ten-year old’s assessment? “It’s fine dining, meets fun dining, dad.”—K.S.

1981

THE ODEON, New York

The perennial downtown hangout.

1985

JOE’S STONE CRAB, Miami Beach

AUBERGE DU SOLEIL, Rutherford, California

1986

LE BERNARDIN, New York

The holy grail of fresh- fish fine dining.

1993

DANIEL, New York

1994

THE FRENCH LAUNDRY, Yountville, California

NOBU, New York

1997

BALTHAZAR, New York

1999

DANIEL, New York

2005

PROVIDENCE, Los Angeles

Pristine seafood with Cali-magic.

2006

JOËLROBUCHON, Las Vegas

2008

ZAHAV, Philadelphia

You haven’t lived until you’ve had the lamb shoulder.

2011

FIOLA, Washington, D. C.

COTOGNA, San Francisco

2013

THE ORDINARY, Charleston, South Carolina

Daiquiri and oysters are a sublime combo.

ROLF AND DAUGHTERS, Nashville

2015

THE GREY, Savannah, Georgia