As the Colorado River sinks further into crisis and tensions rise between Western states over how to divvy up painful water cuts, a bipartisan group of senators are formalizing a new caucus to examine how Washington could help.

What began as an informal group convened by Democratic Sen. John Hickenlooper of Colorado has grown to a council of senators that represent seven Colorado River basin states – Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, Arizona, California and Nevada, according to Hickenlooper’s office. Details of the group were shared first with CNN.

What to do about the shrinking Colorado River and in the vanishing water in America’s largest reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, has quickly become the most pressing issue for these Western senators. The river’s water sustains 40 million people, some of the West’s biggest cities and major agricultural hubs.

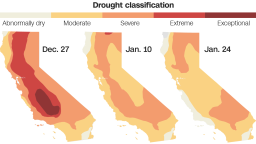

“I think the Senate should be partners” with the states, Hickenlooper told CNN. “There might be additional resources that are needed to really solve this. I think most experts feel this is not just a drought – there is some level of aridification, desertification.”

Experts have previously told CNN that the term “drought” may be insufficient to fully describe the transformation the West is experiencing. Eric Kuhn, a retired former manager of the Colorado River Water Conservation District, has said that “aridification” – a shift to a much drier climate – is likely more accurate.

Talks between the lawmakers are in early stages, but some senators are looking at ways they can provide additional financial assistance to states and water users that are likely facing substantial water cuts. Democrats passed $4 billion in drought relief funds for states, tribal nations and farmers last year in the Inflation Reduction Act; that money is in the process of being distributed by the federal government.

The senators are also hoping to ease tensions between California and the other six basin states, which are at an impasse on how to spread the water cuts needed to save the Colorado River. The group of six states recently released a proposal to cut millions of acre-feet of river water, while California separately released a smaller proposal that keeps senior water rights for its agricultural users intact.

Sen. Michael Bennet, a Democrat from Colorado, told CNN he is looking at the upcoming farm bill as a vehicle to get more funding for Western water conservation programs. Bennet said senators will “think about what future funding might look like.”

So far, there is little appetite among this group for Congress to intervene in other ways, such as clarifying or expanding the US Bureau of Reclamation’s ability to make unilateral cuts of Colorado River water.

“A federally mandated solution and litigation will leave everyone worse off,” Independent Sen. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona told CNN in a statement. “The Colorado River belongs to all of us and we either fail or succeed as a region.”

What can Congress do about the Colorado?

Two Colorado River experts told CNN that it’s probably wise for the Senate to focus on funding over passing laws that would weigh in on the cuts themselves.

“The most important thing Congress can do is provide funding that helps get all the different water users and the states to agree on a plan going forward,” said Sarah Porter, the director of the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University.

Michael Cohen, a Colorado River expert at the California-based water nonprofit Pacific Institute agreed that more funding could lower interstate tension.

“Additional funding will tamp down tempers and make it easier for additional water users to participate,” Cohen said. “That is key.”

Even though Congress already passed $4 billion last year for drought relief, experts and senators alike said more is needed.

“Do I think we’re going to need more than $4 billion? Yes,” Democratic Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto of Nevada told CNN. “We see the urgency of solving this crisis, we have to do more to combat drought.”

Congress may also be able to play some role in US and Mexico negotiations over that country’s Colorado River allocation, Cohen added.

But Porter conceded that more funding to pay people to cut their water usage is a short-term solution. The long-term – and far more thorny – problem is how farmers, cities, and tribes will permanently reduce their water use. And Congress weighing in on the Colorado River Compact formed more than 100 years ago would probably be litigated, Porter added. That compact between states is a complex agreement between states on how and when cuts will be made as water declines – and who has priority rights to it.

“These pre-compact rights are part of the whole knot that needs to be untangled here,” Porter said. “(Congressional) legislation probably can’t do much about that, and I’m sure there would be litigation if it attempted to.”

A divided West

The divide between California and the six other basin states is reflected in the Senate.

In a joint statement last week, California Sens. Dianne Feinstein and Alex Padilla – both Democrats – wrote that “six other Western states dictating how much water California must give up simply isn’t a genuine consensus solution.”

Padilla told CNN in a statement that he would work with other Western senators to help secure additional money “to support our communities’ long-term water needs.”

“All Senators have a role to play when it comes to encouraging and facilitating the difficult, but necessary, changes within our respective states to better balance the water needs of cities, agriculture, and wildlife,” Padilla said.

Hickenlooper and other senators told CNN they hope the group can ultimately help avoid a looming legal battle between states and the federal government if the Bureau of Reclamation has to step in and impose its own cuts. That is looking more likely as the seven states have repeatedly failed to reach an agreement, with California a notable holdout.

“We don’t have time to go through the courts and then have appeals and resolve that,” Hickenlooper said. “I think there is a real push to solve our own problems without having to litigate.”