Editor’s Note: Elizabeth Palley is a professor of social work and director of the doctoral program at Adelphi University School of Social Work and author of In Our Hands, the Struggle for US Childcare Policy. Howard Palley is professor emeritus at the University of Maryland School of Social Work. The opinions expressed in this commentary are their own.

The coronavirus pandemic has put Americans’ strained childcare system into a full-blown crisis. We must recognize that we cannot rebuild our economy without first repairing our fractured family care infrastructure.

Make no mistake, fixing childcare is expensive. Indeed, President-elect Biden’s caregiving plan, which calls for universal pre-K, subsidies for low- to moderate-income families, expanded tax credits for families and better pay and benefits to childcare workers, would cost an estimated $775 billion over 10 ten years.

But we need to think of this as a stimulus bill, not as a tax burden.

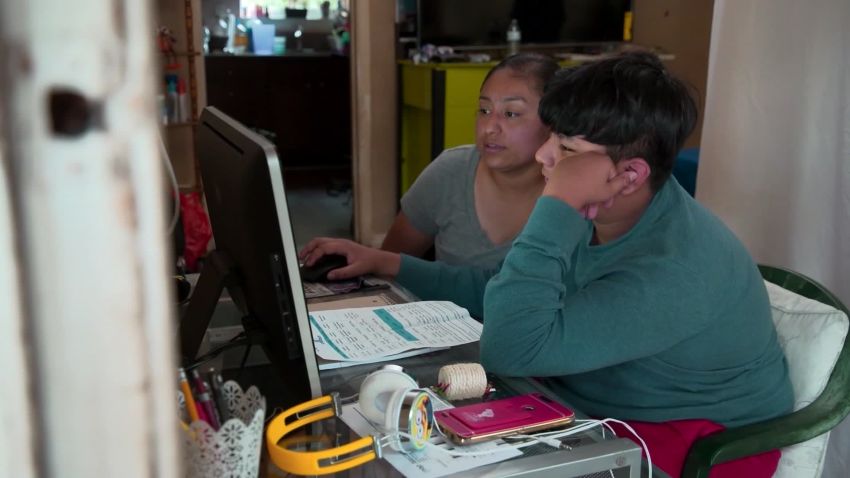

Even before the pandemic, most women – who are often the primary providers of childcare – could not afford to stay home with their children. According to the most recently available national data, approximately 35% of children under 6 were in non-parental childcare at least 30 hours a week. Suddenly forced to work from home, facilitate online school and provide 24/7 childcare and household duties, millions of women have been forced to leave the labor market. We don’t yet know what the long-term impact on women’s employment and career options will be, but if women struggle to, or are not able to, return to work after Covid-19, it is evident that they and their families will be further harmed financially.

The problem will only be exacerbated because our nation’s childcare providers are struggling to keep their doors open. Childcare workers are currently among the poorest-paid workers in the country, earning a median income of $11.65 an hour. Government support for care is needed because it costs money to ensure that there is an educated childcare workforce. The ratio of providers to children also needs to be sufficiently small to ensure quality of care.

Quality of care is relevant economically, too. There is extensive research about the positive impact of high-quality childcare, particularly on young children. Beginning in the early 1970s, with the Perry Preschool Project and the Abecedarian project, longitudinal data has supported the benefit of high-quality care for children and taxpayers. Low-income children who attend high quality care are less likely to be incarcerated, more likely to be employed, have higher IQs, more likely to graduate from high school, more likely to attend college and less likely to be on public assistance than their peers.

Though voters across party lines support federal and state funding for childcare, there are inevitable concerns that such expensive services will raise taxes. These naysayers seem to forget that a lot of the federal and state money spent on childcare will go back into the economy. National childcare should be viewed like many of the programs in the New Deal Era of the 1930s, which were used to help pump up a struggling economy.

From its earliest days, the coronavirus pandemic has exposed how necessary early care and education are to making America work. Rather than viewing childcare as an unsupportable tax burden, investing in high-quality childcare should be seen as an essential public policy and a necessary part of stimulating our struggling economy.