In February, a year ago, the top scientists at the Georgia Department of Public Health (DPH) gave a briefing to its advisory board about the novel coronavirus.

Days earlier, President Donald Trump had imposed a travel ban on China and the federal government declared a public health emergency. At the time, no Georgians were confirmed to be infected though some 200 people in the state who’d recently traveled to China were self-monitoring for symptoms, meeting minutes show.

“The potential for a global pandemic is high but the risk for most Americans is low,” a slide from the Feb. 11, 2020, meeting read. The state’s top epidemiologist also warned about influenza, which had killed more than three dozen people in Georgia to that point.

It was the last time DPH’s board met. The agency cancelled subsequent monthly meetings and the board has been dormant ever since.

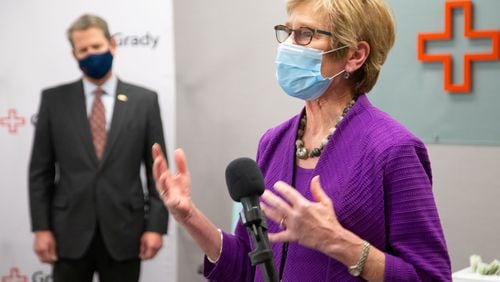

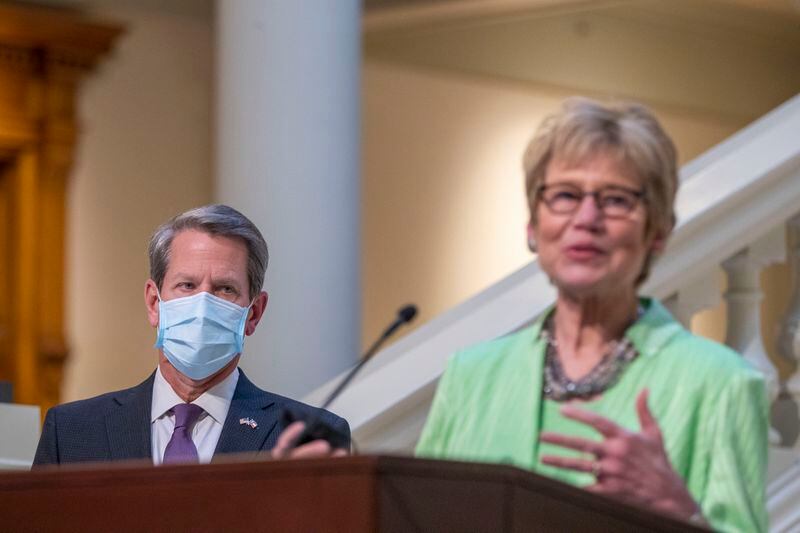

DPH Commissioner Dr. Kathleen Toomey defended her agency, pointing to dozens of media briefings and public appearances she held over the past 15 months. She said the agency suspended the advisory board meetings because the strain on department staff to prepare for them “(was) not the best use of everybody’s energies.”

”We made a broad decision in discussions with various leadership that we would not have meetings at this time, but really invest in the work of the pandemic,” she said. “Because our epidemiologists were tied up.”

Critics counter that the failure to hold public board meetings amid a pandemic that has killed more than 17,850 Georgians is a stunning lack of transparency and accountability for an agency leading the state’s response to the plague.

During the time the board was mothballed, the agency faced repeated challenges associated with its management of the pandemic, including how it collected and processed data, handled early testing and conducted contact tracing to identify exposure to the virus.

“Why would a board dedicated to public health never have met during the entirety of this pandemic?” said Richard T. Griffiths, president emeritus and spokesman for the Georgia First Amendment Foundation. “Even if they are not making key decisions, it would have been a vital way for the public to understand what’s going on in Georgia and how the state’s public response was taking place and provide context for the state’s response.”

State leaders facing questions not just from the media but from other subject-matter experts is invaluable for both public knowledge and forming strategy, experts said. And such a board of experts can also serve as a powerful megaphone to amplify DPH initiatives, they said.

DPH board dates to 2011

The General Assembly created the Board of Public Health a decade ago when DPH was removed from the Department of Community Health and became a standalone department.

The agency oversees public health emergencies, epidemiological investigations and laboratory services to detect and control disease, health and disease screenings, routine vaccinations and immunization records and other functions. It’s part of a complex public health bureaucracy that includes county health departments, some of which DPH runs, and regional district offices.

Unlike the State Board of Pardons and Paroles or the university system’s Board of Regents, the Board of Public Health is not a governing body.

But the nine-member public health board is appointed by the governor and confirmed by the Senate to help form policy and advise DPH. The members receive a daily expense allowance for meetings and reimbursement of expenses, under state code.

The group is chaired by James Curran, a celebrated former Centers for Disease Control and Prevention AIDS researcher and the current dean of the Emory University Rollins School of Public Health. Its vice chairman is John Haupert, CEO of Grady Health System.

During meetings, typically the second Tuesday of each month, the board is informed of DPH initiatives to tackle infectious diseases and other health concerns, and actions are duly noted in minutes. The board advertises meetings and they are attended by members of the public and media.

The first-ever meeting of the Board of Public Health occurred in October 2011 and was held via teleconference. Action included approval for DPH to sell $500,000 in bonds to fund renovations to three facilities.

During a Hepatitis-A outbreak in Georgia that started in 2019, the board was briefed on the state’s response and members questioned DPH leaders about strategy and outreach efforts.

Former state Sen. Renee Unterman, R-Buford, who pushed the legislation making DPH its own department, said the idea of the Board of Public Health was to promote transparency.

No meetings, no public record

Toomey told the AJC the board might hold a special meeting in the weeks ahead to approve state bonds and its first regular meeting is scheduled to be held virtually in September.

The commissioner said that even though the DPH board was not meeting publicly for the past 15 months, she was holding regular conversations with its members.

“I certainly was talking to the board chair frequently, and he was communicating with the other board members,” Toomey said. “Many of the board members were doing vaccinations. And many of the board members were actually reaching out to me to help set up some special sites. So we were engaging on the ground throughout this.”

Curran, the board chairman, echoed Toomey’s position in an emailed statement to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

“Even without the scheduled meetings, Board of Health members remained active in supporting GDPH and regularly provided guidance, as needed, specific to our areas of specialty,” Curran wrote.

Greg Lisby, the chair of the Department of Communication at Georgia State University and an expert on open government, said public discussions about the pandemic among experts would likely be of vital public interest in an emergency.

If a board meeting were held, the public could attend or review minutes and presentations. But a private briefing might leave no public record trail, he said, unless the contents also were written and retrieved via an open records request.

Holding private briefings could be seen as an end-around of the Georgia Open Meetings Act, which requires boards to hold public meetings in most circumstances if there is a quorum of members, Lisby said, and that would not instill trust in government.

“Any group that influences public funding, public policy and public behavior should really default to public meetings,” he said.

But, Lisby added, the law is generally silent on whether a board like the public health panel needed to have any meetings at all during the past 15 months. But if they do, he said, they need to be public.

Throughout the coronavirus pandemic, local and state government bodies — from zoning boards to county commissions — found ways to safely meet to discuss matters of public concern, while staying in compliance with the Georgia Open Meetings Act. Many held their meetings virtually and took public comment through email and voicemail.

DPH has held virtual meetings for its health equity council in March and another related to a grant program last year.

With respect to the advisory board, Griffiths said: “The First Amendment Foundation would like to offer them our Zoom account information so they can meet.”

Lawmakers sympathetic

Unterman, the former state senator from Gwinnett County, said she sympathized with DPH leadership who faced the demands of confronting an unrelenting pandemic with limited time and resources. She said Toomey found other ways, such as numerous media appearances, to communicate to the public.

“It’s not a waste of energy but it’s a sideline to what you’re doing in a crisis,” Unterman said of the board. “You have to prioritize what you’re doing.”

State Sen. Nan Orrock, D-Atlanta, also cut DPH some slack. She said public health in Georgia has been stymied for decades by a lack of funding and the department was grappling with a crisis. Orrock said DPH and the governor’s office provided lawmakers with weekly briefings.

The governor formed a coronavirus task force of experts in emergency preparedness, medicine, infectious diseases and social and government services. Committees within that task force met numerous times over the course of the pandemic, said Cody Hall, a Kemp spokesman.

Hall said the governor’s office has no role over the scheduling of the Board of Public Health. But Hall vigorously defended Toomey, Kemp and other state officials, pointing to the governor’s numerous press briefings and public appearances, in which Toomey regularly spoke.

Credit: Alyssa Pointer / Alyssa.Pointer@ajc.com

Credit: Alyssa Pointer / Alyssa.Pointer@ajc.com

“Dr. Toomey participated in dozens and dozens of media interviews, press conferences, and public appearances,” Hall said in an email. “I haven’t counted, but I would assume that number is over 100 at this point.

“As you know, those press conferences sometimes lasted up to an hour, where Dr. Toomey, the Governor, and other state officials would answer each and every question,” Hall said.

Hall said any impression that Kemp’s office or DPH were inaccessible to the media or the public “would have to ignore basic facts about how we regularly provided public updates throughout the pandemic.”

Unterman said the Board of Public Health should meet when the pandemic eases and be part of broader conversation with the Legislature over how public health is better funded and structured in Georgia.

“I think they need to regroup,” she said. “They need to reassess once this crisis is over, they need to regroup and there needs to be new legislation.”

Orrock concurred.

“When we hit daylight, when we get out of this pandemic, it would be very appropriate to look at how public health is structured and what it’s needs are,” she said. “We found out as a state and nation that public health has a vital role to play.”

Staff writer Ariel Hart contributed to this report.

Members of the board

The Board of Public Health includes nine members who are mostly engaged in public health, medicine and research.

Dr. James Curran, chairman, dean of the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University

John Haupert, vice chairman, president and CEO of Grady Health System

Dr. Mitch Rodriguez, neonatologist

Maj. Gen. Thomas Carden, adjutant general of the Georgia Department of Defense

Dr. Kathryn Cheek, pediatrician

Dr. Robert Cowles, urologist

Dr. Cynthia Mercer, OB/GYN

Dr. Ryan Shin, health services researcher

Dr. T.E. Valliere-White, surgeon

Source: Georgia Department of Public Health

About the Author