Lead exposure may contribute to more than 400,000 deaths of adults each year in the U.S., according to an estimate published today in the journal Lancet Public Health.

That number includes 256,000 annual deaths from cardiovascular disease, suggesting that lead exposure may be a significant, overlooked risk factor for this leading cause of death. The estimate was extrapolated from a nationally representative sample of 14,289 adults, whose blood had been tested for lead sometime between 1988 and 1994.

Lead exposure is "ubiquitous, but insidious," the researchers have written.

People can be exposed to lead through paint, household dust, food, water, and cigarette smoke, as well as through some industrial jobs. Childhood exposure to lead is known to increase the risk for delayed development, behavior problems, IQ deficits, hearing and speech problems, and more, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Lead levels in children were much higher until the 1970s, when lead was removed from gasoline and paint. But while lead exposure is considered a risk factor for heart disease and both the CDC and the Environmental Protection Agency have warned that lead is unsafe at any level, this is the first study to quantify just how severe the toll might be—even at the lowest levels, and even decades after exposure.

The research underscores the danger lead poses not only to children but also to adults, according to Bruce Lanphear, M.D., M.P.H., a professor of health sciences at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia and the study's lead author. "There's no apparent threshold or safe level [of lead] for deaths from heart disease," he says.

Here's what you need to know about this research and what you can do to protect yourself now from the dangers of lead.

What the New Research Found

While this new estimate is staggering, the results should be interpreted cautiously, experts say.

One limitation: Lead levels in the blood were measured only once. Lead may be stored in the body for years after initial exposure, but the concentration of lead in blood can change over time. Other potential risk factors, such as diet and smoking habits, were also assessed only once and were not tracked over time. And while the researchers controlled for other risk factors to try to zero in on the effects of lead, they acknowledge that they were not able to account for everything that might contribute to the deaths.

For example, says Eliseo Guallar, M.D., Dr.P.H., a professor of epidemiology and medicine at Johns Hopkins University who wasn't involved with the new study, "lead exposure might be a marker also of disadvantaged socioeconomic status," which may be linked to risky behaviors or conditions (such as higher rates of air pollution) that the new study couldn't adjust for.

Average blood lead levels are also probably lower today for the general population than they were in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the initial data for the new study was collected, says Ana Navas-Acien, M.D., Ph.D., professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University in New York City who also wasn't involved with the new study. So while the study included people who died as recently as 2011, the number of deaths that can be linked to lead may be smaller today. "We'd expect somewhat less risk for the next generation," Lanphear says.

Still, both Navas-Acien and Guallar say that the new study is convincing overall and highlights the often-ignored impact that lead exposure can have on heart health. The pair collaborated on a study released last year that evaluated the same data that Lanphear's team used and found that approximately a third of the decline in heart disease deaths from the early 1990s to the early 2000s could be explained by reduced exposures to lead and the heavy metal cadmium.

How to Protect Yourself From Lead

Lead is no longer allowed in gasoline and paint in the U.S. and many other countries. But the substance can still lurk in unexpected places.

Here, what you can do to reduce your exposure to lead.

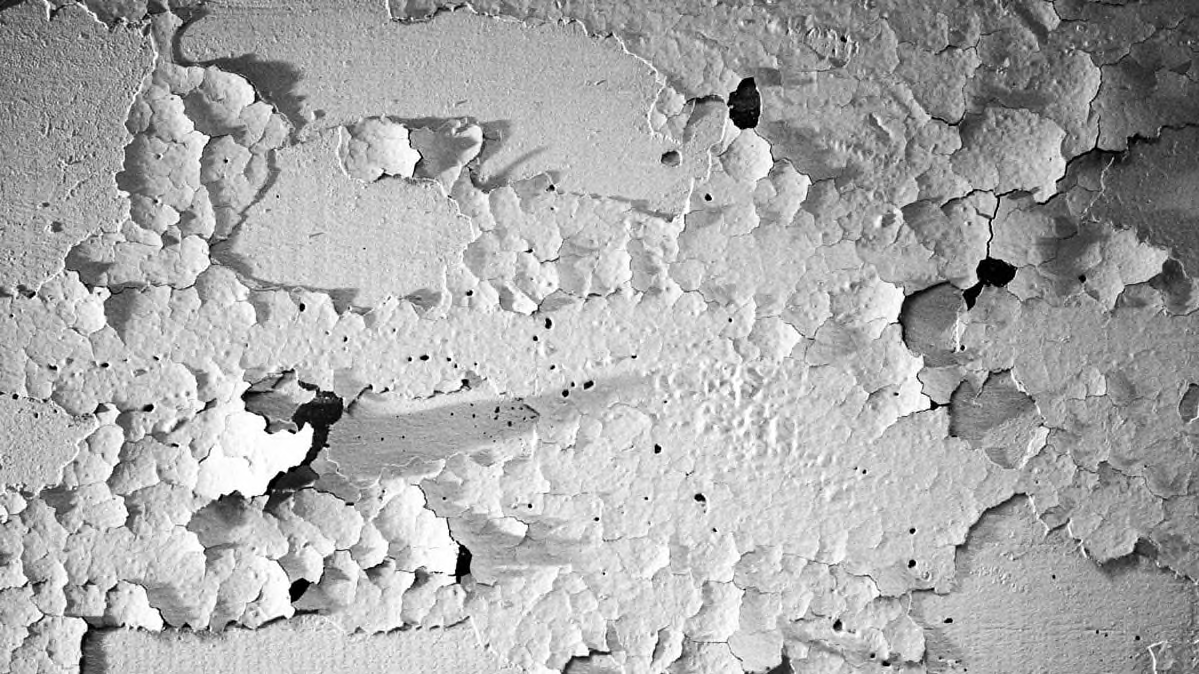

Check for lead paint. If your home was built before 1978, it's likely that at least some lead paint was used in it. As the paint degrades, chips, or crumbles from normal use or renovation, it gets into household dust, which can find its way into your system when you breathe or accidentally inhale it. You can test for lead in paint using a kit available at your local hardware store. For detailed instructions on how to get the test right, see our guide here.

If you do find lead paint, don't sand, scrape, or demolish the surface on your own. You'll first need to hire an EPA-certified lead-abatement professional. Or you can paint over the contaminated area yourself, provided you don't disturb the leaded layer.

Beware of lead pipes. If your home was built before 1986, its water pipes could contain lead and you should use only cold water from the tap for drinking and cooking. According to the CDC, hot water is more likely to contain lead. And you may want to have the water in your home tested for lead. (Find a certified lab here.)

Have your children tested. The CDC recommends that children at high risk for lead exposure receive a blood test for the toxin at six months, and at one year for children at low risk. A number of factors can affect kids' risk—including living in or regularly visiting a home built before 1978 that has chipped or peeling paint or that is being (or was recently) renovated. Your doctor can help you figure out your children's level of risk, and when they should be tested.

Pay attention to recalls and other news about lead. "Studies show that lead exposure from consumer goods is not insignificant," says Tunde Akinleye, a test program leader in Consumer Reports' Food Safety Division. The toxin is sometimes discovered in common products such as lipstick, toys, and more. Sometimes these products will be recalled; other times, scientists test items for lead and publicize their findings. Akinleye recommends that consumers pay attention to these reports and look for alternatives to products found to contain the highest amounts of lead.

For example, a recent analysis by the Clean Label Project found lead and other heavy metals in protein shakes and powders, and reported which brands had the highest and lowest levels of toxins. Consumer Reports has tested for lead, arsenic, and cadmium in juice and rice products, and continues to regularly test consumer products for lead.