Teaching Palestine

An interview with Palestinian educator Ziad Abbas

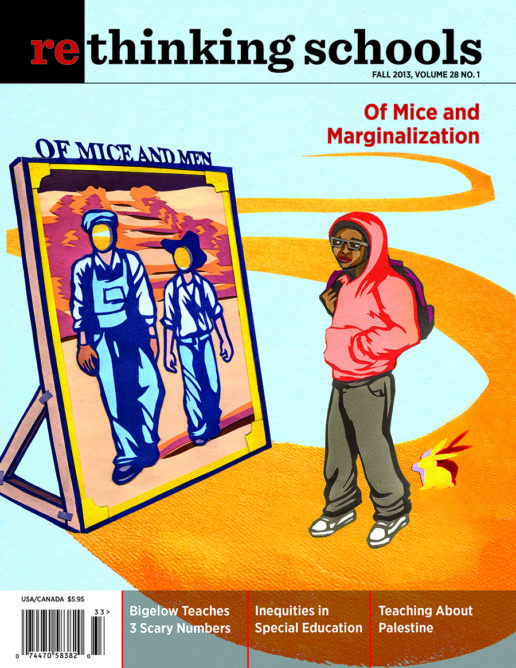

Illustrator: Ericka Sokolower-Shain

Many teachers are reluctant to teach about Palestine. We worry about negative reactions from administrators or parents. Few of us learned much about the Middle East in our own schooling, and it’s difficult to find good curriculum.

But just as it’s important to teach the real history of Columbus, it’s important that students learn factual history and are able to think critically about Palestine and Israel. Otherwise, they are left with the stereotypes so widely disseminated in the mainstream media. The increasing volatility in the region only makes the issue more urgent.

As program manager for cross-cultural programs at the Middle East Children’s Alliance (mecaforpeace.org) in Berkeley, California, Ziad Abbas works with teachers, teacher educators, and students. As a Palestinian refugee himself, born in a camp in the West Bank, he shares his family history, his knowledge of the region, and his commitment to critical thinking and social justice. He spoke recently with RS Managing Editor Jody Sokolower about his own background, the context for teaching about Palestine, and ways to approach the topic with students in the United States.

Jody Sokolower: I know you have been an educator for a long time, both here in the United States and in Palestine. Can you tell us a little about your background?

Ziad Abbas: I was born in Dheisheh Refugee Camp, which is in Bethlehem in the West Bank. In 1948, 18 years before I was born, my parents, my sister, and brother were living in Zakarriyah village near Jerusalem. My father’s family had lived there for centuries. As part of what we Palestinians call the Nakba (“catastrophe” in Arabic), Zionists attacked and destroyed the village – burning houses, firing mortar rounds from tanks, and shelling homes by air. The villagers – farmers and shopkeepers – were unarmed and had no means to defend themselves. My family fled to hide in the mountains. Before they ran, people locked their houses and took their keys with them, imagining they would be gone for only a few days until things were safe again.

The Red Cross and United Nations set up temporary camps to help people to survive. The camps were nothing but tents, and life was extremely hard. Everyone waited for the international community to bring justice and allow them to return to their homes.

I was born into this situation. My mom worked hard and did all her best just to help us to survive. We didn’t have any programs for children, so the only place we went was the United Nations school. The school was just a room where we could spend some time. The curriculum was censored by the Israelis. Sometimes we learned things, of course, but I remember my classrooms had 60 or sometimes 70 students with one teacher.

As a result, much of my education came from home or from the narrow alleyways of the camp where we tried to find enough space to play. Much of the time we lived under curfew. After the United Nations added buildings to the camp, entire families lived crowded into small rooms, unable to breathe. There was not enough water or even enough food. Even today, 13,000 people, mostly children, live in less than a square mile, controlled by the Israeli military. We learned to share everything, and people developed a strong commitment to our community and its struggle for justice. This was the way we grew up.

Dancers as Activists

JS: How did you start working with children?

ZA: My training is as a journalist. Through journalism I encountered many human rights organizations; one was a French group called Discovery. Back in 1994, Discovery wanted to take 20 Palestinian children, ages 12 and 13, to France to meet French children the same age. The children would spend three weeks together, teach each other about their communities, and do a common project. Discovery wanted to connect children facing hard times in Palestine with children in France.

So they approached me. No one had done a program like this in Palestine before, and especially no one had done it in a refugee camp. I said, “Let me think about it, just give me some time.”

I contacted a friend of mine (we played on the same soccer team) who was teaching in a school. He told me I was crazy. In that period, my camp was surrounded by a fence 8 meters high. We had one gate, and the entire camp was under Israeli military control. It was a struggle for us to go outside the camp. How could we go to France? But I thought, what do we have to lose? Nothing. Let us try to do something. I was dreaming. I wanted to travel, I wanted to go outside and see new things. My friend, the teacher, he said, “OK, let us try.”

So we started Ibdaa, which means “creativity” or “to create something out of nothing” [in Arabic], because we were missing even basic necessities in the camp. We had nothing except our dream to gain our right to return to our homeland. The idea was to create a pure refugee initiative, a place that young people could express themselves and a forum for them to communicate their situation to the larger world.

Our young people are determined to never accept the degradation and humiliation the occupation puts on them. They throw stones at the Israeli soldiers and tanks in the streets. It is very dangerous. Many of our children have been killed or injured or become disabled at an early age.

In that period, we had many children who were injured. They had a lot to say about the solutions they hoped for, but they had only one way to express their anger at the occupation, in the streets. We decided that our children deserved more ways to express themselves, to express their struggle for their right to return home. So we started this project, born inside the refugee camp and protected by the community.

One of the first challenges we faced was how to choose the children. We decided to have an election. An election was a new idea. We had two schools, a school for girls, a school for boys. We spent the next two weeks teaching all the children the meaning of elections, how to vote, why do we do it. Because of the occupation, we had never had experience with democracy. In the end, we elected 20 girls and 20 boys.

From the beginning we had girls and boys together. This was a conservative community and they didn’t accept girls and boys together. Even for the children, it was hard. One thing that helped to connect the children was talking about reality: “We are refugees living behind the fence. We want to come together as a team to represent what’s happening on this side of the fence, inside our refugee camp. It’s not something that only affects us as individualsÑwe want to represent the community.”

Discovery asked us to present something from our culture during our visit to France. We decided to tell the Palestinian people’s story, not through speaking, but through dance. So we designed a show called The Tent because it was going to be about refugees. We tried to make it a story.

When we elected the children we weren’t thinking of them as dancers, but in a few months they became a dancing group. We were prepared to dance for only one time in France.

We performed the first show in Paris. We ended up traveling throughout Europe and later to the United States, telling the story of Palestine through dance. I did that for 15 years. During this period I learned a lot from the children. They were the main contributors to who I am today.

You Say “Palestine.”

They Ask, “Pakistan?”

JS: Now, after many years of working with Palestinian youth, you’re in the United States, teaching about Palestine. What do youth here know about Palestine? Are they interested?

ZA: The Middle East Children’s Alliance (MECA) receives many invitations to speak in schools about the situation in the Middle East in general and about Palestine in particular. When I ask the children, “Do you know Palestine?” I will be lucky if I find a few hands raised. Sometimes there are children who have their own connections – they are immigrants from the Arab world or they come from a family of political activists, something like this. But the majority of the children, no. And with the adults, it is almost the same. You say “Palestine,” they ask, “Pakistan?”

JS: How do you begin to build ties with those students? To make them care about what is happening in a country on the other side of the world?

ZA: When I traveled with the Ibdaa dance group, we performed in many places and gave workshops at schools. One experience we had was at the South Valley Academy in New Mexico, a very poor school with many immigrant students. The Palestinian children were all of a sudden very relaxed. They felt at home, like there was a connection when they danced. One of the Chicano students even said, “This is a story about us, not just about you.”

So I learned from the children to make connections between Palestine and their lives. I try to reach out to the students in front of me, to understand where they are coming from. Privileged, unprivileged, immigrants. Sometimes I try to be funny so they can accept me. And I try to connect things to their reality.

I was in a school in San Jose and most of the students were from Latin America. I started talking about the borders. What the borders mean for them and anyone from their family, for anyone deported, and what borders have meant for my own family. I told them the story of my family, how my parents had to leave their homes and now my family is scattered in countries all over the world. I try to connect their story to my story.

Sometimes I push, to encourage them toward critical thinking: “Why are we seen as different from other people? Why is this happening that some people are forced from their homes? Why are Palestinians living like this?” I show them the map – the tiny space where Palestinians are allowed to live in the West Bank and Gaza. “Why are the Israelis trying to control this?”

It is similar for many new immigrants here. I explore with the students why people are forced to leave their homes and have to live here without the right documents. Being called “illegal” makes people feel insecure all the timeÑthey are afraid to be arrested and deported. What does it mean to be deported? To be jailed? This is where I can make a connection.

We can only plant the seeds. I try to use different ways to approach the meaning of oppression: If someone came to take your house, and after that pushed you to the garden, and later pushed you and your family out of your garden and even your city, what should you do? This is what happened to Palestine. How would you react if this happened to you? How should I react, because it has happened to me? This is the best way they can take my story. I target their hearts, their minds, their feelings. I want them to feel what this means.

Sometimes I speak about jail, and the experience of going to jail. When I talk about my going to jail as a child, when I tell them that children their own age are in Israeli jails because they are struggling for their rights, it motivates them to start asking more questions.

JS: You were young, right?

ZA: Yes, I was 14 the first time. Along with dozens of other teenagers, I was accused of throwing stones at the Israeli troops. When I speak about that, it shifts the feeling in the room. I get different questions. Instead of questions about how I grew up in the refugee camp, the students ask about jail. Did they torture you? How did they treat you? And they compare it with jails here in the United States. So this is the frame I use. I want them to be in my shoes. To start thinking about this.

In U.S. history, students learn about Manifest Destiny. I compare that with the Israeli concept of the Promised Land. I ask them: “Why would God give the land to these people and punish these other people because of their color or who they are? Why would this happen to Native Americans? Why to Palestinians?” Israelis say that God promised the Jewish people the land to make it their country. I encourage the students to go deep inside themselves and think about this. “Does this make sense? Did God say this?” These concepts – Manifest Destiny and Promised Land – do not fit when it comes to justice or political rights.

I talk about who gets resources and who doesn’t. For example, for us water is a big issue. The aquifer under the West Bank where I grew up goes to give water to Israel – the Palestinians living right on top of the aquifer only get to buy the water from Israelis at high prices, while Israeli settlers get the water at very low prices. For many summers, when we didn’t have enough to drink, I saw settlers filling their swimming pools and washing their cars.

Because of the theft of our groundwater, Palestinians are left with little water or polluted water. This is why MECA started the Maia Project. We build small water purification and desalinization systems for schools in the Gaza Strip.

Since I came to the United States I am enjoying two things: I can take a shower every day. And I can drive my car wherever I want. At home it is very hard because of the hundreds of checkpoints. For example, I can’t go to Jerusalem even though it is less than 10 miles from my refugee camp.

A Framework for Curriculum

JS: What are the most important things for students to learn about Palestine? What is the framework through which we should be seeing this situation?

ZA: There are certain principles: oppression and oppressors, justice and injustice. As Martin Luther King said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” I don’t want someone to support Palestine and be against women’s rights. I don’t want someone to support Palestine but be against gay rights. All these issues are connected to each other. We need to teach children the principles. And Palestine is one of the clearest examples of injustice in the world today.

It is important to look at the whole history. If you start it from the Holocaust, you cannot understand what happened. It distorts the history. I try to start with how things developed. The first Zionist settlement in Palestine was in 1878; the first Zionist Congress was in 1897. In 1917, in the Balfour Declaration, the British, who were the colonizers then in Palestine, promised it to the Zionists. By the 1920s and ’30s, Zionists were organizing Jews all over the world, especially in Europe, to settle in Palestine. Before World War II began, the Zionists had maps of all the Palestinian villages, lists of local leaders, and plans for how to force Palestinians out of Palestine. So it is important to put the history in 1948 and beyond in this larger picture.

Teaching about Palestine should be based in international law and respect for human rights. Under international law, especially U.N. Resolution 194, Palestinians have the “inalienable right” to return to their homeland. There are 11 million Palestinians in the world; 7 million of us are refugees in the Gaza and West Bank, in neighboring countries in the Middle East, and around the world. Resolution 194 was first passed in 1948; we are still waiting to go home. I have the key to my family house that my mom gave me before she died.

Palestine has been facing an apartheid system, especially in education. Most schools are segregated. Palestinian classrooms have poorer buildings than Israeli classrooms, fewer teachers, larger class sizes, fewer resources. Sometimes teachers can’t even get to the school because of the checkpoints. This discrimination is another connection that children in the United States will understand.

JS: Why do you think so few teachers in the United States teach the history or current reality of Palestine?

ZA: The education system in the United States, like the media, is controlled. As Palestinians, we do not exist. If I see a map in the classroom, I ask the students, “Can you find Palestine on the map?” They go search and they will not find Palestine. “OK, can you find Israel on the map?” They go and they will find Israel very fast.

The U.S. education system, it is censored in that it dehumanizes “the other” so they do not exist. The focus is on teaching Manifest Destiny and Thanksgiving and Columbus-discovered-America. It means that you hide the Native American. It’s the same thing as teaching the beginning of Israel as if it were because of the Holocaust – that somehow Israel was the solution to the Holocaust.

Teachers are victims of this education system, too. I wish that all the teachers in the United States knew about Howard Zinn, and that they were trained to teach children to think critically about the information they receive from teachers, their parents, and from the community. To help them to build their own perspectives and ideas.

Those teachers who are teaching about Palestine, it’s often because they feel secure, they don’t feel afraid for their jobs if they are attacked by the Zionists. They believe in social justice and struggle. And, also, they know their responsibility for what the United States is doing to other peoples, they make those connections. Many other teachers want to speak but they don’t know what’s happening in Palestine, or they have never examined this issue in their school.

JS: Another barrier to teaching Palestine is fear of negative reactions from parents and administrators.

ZA: I know that teaching Palestine is a risky thing to do. I had one experience where the teacher was forced to leave the school by the end of the year because she invited me to speak.

JS: She didn’t realize what a firestorm that would cause.

ZA: She didn’t realize at all. She’s African American, the headmaster was African American. They were teaching about social justice and human rights. They thought they were very radical. She didn’t realize the minute it comes to Palestine it’s a different issue. This teacher, however, never regretted that she invited me. She told me that as someone committed to social justice, she needs to teach about human rights abuses everywhere, whether they are in Africa, in the United States, or in Palestine.

These Zionist groups are very well organized. They try to target everyone who talks or teaches about Palestine. They want to shut down everyone who tries to put this issue on the table or tries to teach about it. But people are resisting these attacks. Recently I’ve been invited to many schools and conferences to present about Palestine. Many teachers are refusing to be intimidated and are insisting on their right to teach about human rights. Because of this, things are changing. I am very proud that there are many teachers doing this.

Getting Started

JS: I think there are many teachers who would like to teach about Palestine, but they feel they don’t know enough. If someone wanted to get a basic understanding of the history and current situation, what would you suggest?

ZA: When I care about an issue, I follow it in the news. That’s a place to start (see Resources).

Then, to understand the background, I recommend The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, by Ilan Papp, who is an Israeli Jew; his parents were Holocaust survivors. He puts what happened in 1948 in historical context. He explains, using international definitions, why what the Israelis did to the Palestinians in 1948 was an ethnic cleansing. For Palestinian culture, you can read Ghassan Kanafani. He was assassinated when he was 36 years old, but he documented what happened to Palestinians through short stories. His best-known book in English is Men in the Sun and Other Palestinian Stories. There are documentary films, including Occupation 101, which is a good introduction. Roadmap to Apartheid compares South Africa and Palestine. Promises is a documentary about Palestinian and Israeli children. Frontiers of Dreams and Fears explores the lives of a group of Palestinian children growing up inside refugee camps.

Why Teach Palestine?

JS: There is so much pressure to teach subjects that show up on standardized tests. Why is it important to make time to teach Palestine?

ZA: In the United States, there are special reasons why students need to learn about Palestine. First, it’s a basic human rights issue. People in the United States care about human rights and have a right to know what is going on in the world.

Second, the main supporter of the Israeli occupation is the U.S. government. The United States gives money and human resources to support the Israeli military – this is $3 billion dollars a year that could support school budgets, but instead goes to support the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. The United States gives political support to Israel, especially in international organizations like the United Nations. They try to protect Israel from Security Council resolutions that will criticize Israel or try to enforce Israel’s compliance with international law.

Third, this issue directly involves the people of the United States. Many of the settlers who occupy the West Bank are actually U.S. citizens. They vote in U.S. elections, but also Israeli elections.

Fourth, just to understand world politics, we need to understand the dynamics that involve Palestine. U.S. policy in the Middle East uses Israel to try to control the resources in the region. The United States presents itself as the mediator for peace in the Middle East. In reality, they are supporting the Israeli occupation.

Finally, we cannot have peace in the world without justice in Palestine. It could lead to a third world war; I hate to say it. The new generations in the United States and the world, they need to know about Palestine. They need to know what’s happening in Palestine; they need to know the principles of human rights, the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights, so they can bring peace. Without changing U.S. public opinion and actions about Israel, without the new generation taking a lead toward justice for themselves and for those outside the United States, I don’t think we can have peace in the world.

Sometimes teachers are not just educating children, they are educating their parents, too. You are planting seeds in the children that bear fruit even after they go to the streets, after they go home.

You don’t teach Palestine because you are against Jewish people. You teach Palestine because you believe in certain principles. Teachers need to take a stand. And they should be protected by their principals, by the education system, by their union. This is very important.

Every school is a specific community with its own issues. You need to respect rules, but there are certain rules you need to break. You cannot continue to go along with rules that mean the system can confiscate the right of the people to think – to take a stand and to take initiative.

Educators are creative. It’s beautiful when they connect what’s going on in the world – in Palestine and elsewhere – to the classroom and to their students’ daily lives.

Resources

Websites for Information About Palestine

Books

- Kanafani, Ghassan. Men in the Sun and Other Palestinian Stories. Translated by Hilary Kilpatrick. Three Continents Press, 1998.

- Papp, Ilan. The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Oneworld Publications, 2007.

Documentary Films

- Frontiers of Dreams and Fears. Mai Masri, filmmaker. Arab Film Distribution, 2001.

- Occupation 101. Sufyan and Abdallah Omeish, filmmakers. Triple Eye Films, 2003.

Promises. Justine Shapiro, BZ Goldberg, and Carlos Bolado, filmmakers. Roco Films, 2001.

- Roadmap to Apartheid. Ana Nogueira and Eron Davidson, filmmakers. Journeymen Pictures, 2012.