Last month, I had a chance to interview Sylvia Wynter about the pandemic, Black studies, and radicalism in our current moment. What began as a series of catch-ups over the course of the pandemic, turned into this short interview—a glimpse into the conversations we’ve had over the last several months. This interview revisits some major themes in her work(s), with the added context of our current/ongoing context of the pandemic/rebellion/authoritarian politics. Most importantly, this conversation spotlights her commitment to realizing the Third Event, a break defined by language and storytelling, as the way out of our current and persistent predicaments.

These conversations have also guided my work and thinking as I write my book manuscript, The Interminable Catastrophe, where I attempt to piece together the meaning and transformation of the catastrophic as a concept, from early modern Europe to the Americas. As I write, I return to our conversations on the virus and the global pandemic, to consider how both the problem and a potential break with the problem, begins again, and again, delaying the End while reinscribing its centrality in each repetition. Wynter reveals to us what emerges is an understanding that theorizing and inhabiting the radicality that may help us arrive at the Third Event requires us to tell a different story about our planet as we understand it. Unburdening ourselves of the master script of our planet’s assumed demise is our most urgent task.

In this conversation, we discuss the embrications of education, language and rites of passage, of struggles over discipline and Black studies, of the pitfalls of the state, in this endeavor towards a Third Event.

Bedour Alagraa (BA): In your interview with David Scott, you said that you “wanted us to assume our past: slaves, slave masters and all. And men, reconceptualize that past…” and that you didn’t want us to go for what you called a “cheap and easy radicalism.” I have to say that this is one statement of yours that has really gripped me for a long time. It gestures towards both the predicament of radicalism in which we find ourselves, as well as a possible opening onto something else. Can you talk a little bit more about this need to reconceptualize the past, and the need to refuse ‘cheap and easy’ radicalisms in our current moment?

Sylvia Wynter (SW): You see, when I was speaking of this previously, I was referring to the experience I had while living in Guyana as you know. What I had witnessed there—the failure of Marxist project in Guyana in bringing about the transformation which would cut across the Black/Indian divide—gave me much to think about concerning our problems. Yes, we had supported the Marxists, and we realized very quickly that the state solution given by the Marxists was not sufficient because of the prevalence of race, that the work needs to occur elsewhere, aside from the state. When Jan and I left Guyana and returned to Jamaica, we kept this in our minds. We had to take our work of transforming the society elsewhere into a different arena totally, and that is where you have the Jamaica Journal beginning. It was a way to retell the past and the present at the same time—you see it had belonged to the former masters, and we, being former slaves, took it over totally! We were able to forego that cheap and easy radicalism of simply organizing the state differently and we began to tell different origin stories of who we were as Blacks and as Africans. It was the creative side and the creative working of things which led us to the difference in making claims about who we are. The cheap and easy radicalism does not address the underlying requirement for a total transformation—who are we as Black people, as Africans? The Marxists, and actually no party could give us that. Only we could do it! That is the easy way. The hard way is to reclaim our past, present and future selves, totally!

BA: You know, in thinking about this question of reclaiming our past and present selves, it reminds me of our conversations about what you’ve been reading regarding the Kingdom of Kongo in the 16th-18th centuries, and how it pertains to the idea of ‘initiation’ in societies. Can you explain how this relates to finding a ‘Third Event’ as you call it?

SW: Well, you see I began reading about the Kingdom of the Kongo and initiation ceremonies/rites of passage. In particular, I learned that what we might do better is to refer to ‘education’ as initiation, particularly as Africans. Because in these societies in the Kingdom of Kongo, education consisted of an initiation process into a master script containing the truths of that society. And when the community felt under threat, it used these initiation ceremonies with children in order to reinforce its self-conception.

BA: Sort of like a recreation of its own beginning? Or like staging a new drama concerning its origins?

SW: Yes! You’ve got it exactly right. And you see what happens is that what was once there must die in order for the initiation to occur and entry into the new life. It is a birth through death. And what is important are the ceremonies that occur in order for this transformation to take place—they are ceremonies structured entirely by language and art. The Third Event is so important because it is one that relies totally and completely on language to get us there! And in this country we must begin to think about education as an initiation into a world full of symbols and descriptions about who we are. Thinking of it as initiation helps us to understand the importance of introducing something else into the lives and worlds of children. Initiation also gives an understanding of the symbolic significance of education, and how language and art structure the whole of our existence. We need to re-initiate ourselves, a symbolic life through death, and create ourselves anew!

BA: You know, we have spoken at length about the COVID-19 virus and its effects on people everywhere. Could you offer what you think is the most important consideration that might carry us through this time?

SW: What this virus has shown is that we are in fact a single species, and biological assumptions about us as humans have long been untrue. Yes, we are a single species! But the question of how the virus impacts us differently requires us to grapple with our species nature a little bit differently—it now requires us to recognize that though we have differences in phenotype, these apparent differences are very much a product of how we narrate the origin story. You see, our origin stories that have implemented themselves, lawlikely, have been the result of a relationship between affliction and cure. The affliction of natural sin was given “the cure” of the celibate clergy. And the affliction of natural scarcity was given the cure of economics and Darwinian notions of the descent of man. But these are all simply stories! The affliction of today is one concerned with who we are—and the need for a we. The question is, “What will be the cure?” That is where the Third Event becomes important you see, because it is a recognition that we are a species, but not in the manner we have been accustomed to, that we can narrate this problem in a different way. So the affliction of the virus—what is the cure then? The cure is that we must enact a transformation of the whole entire society, or else something else will come up. We run into difficulties because of this president who doesn’t believe in science of course, but we must also remember that what is required is a new science. The science we do have has led us to this point, you see!

BA: It makes me think about how the African continent, and Africans at home and abroad are being treated (materially and discursively) as it pertains to this virus.

SW: Yes, you have noticed something important! You see, part of what we need to do is to grapple with Africa itself. Because we all originated from Africa, it does not mean that we are all Black, because you do have these phenotypic variations as some may call them due to genome difference, and transformation over time which then is given a governing text of skin-difference. Where Africa as our ‘origin’ becomes important is in recognizing that if we are going to tell a different story of ourselves, we must grapple with the beginnings, in which Africa is not only important for Blacks but the key. They want us to think about Africa as a way to think about affliction but it is Africa that gives us so much of our language world, and gave us much of what has been transformed over time, and continues of course into the present. And so you see, we cannot have the Third Event without Africa right at the middle—because how do you tell the story differently if the beginning hasn’t been grappled with? How can you have a Third Event, without Africa, which has given the world its character, playing a central role in claiming our past, present and future selves? I think this is very important. And now with this virus you see, it is showing that in fact, we are a single species! But we are different yet. And so what is this difference? It is a system that produces the difference but, as I said earlier, it cannot be changed via the normal means. We have to retell the story of the past and the present in order to change the course of this virus. That the virus will not go away without this total transformation you see! So when they say Africans are not being impacted by the virus, while also saying that Blacks here are being especially impacted by the virus, they are creating a story in which we as Blacks are being separated from our past and present selves! The virus does not impact us differently here than Africans in Africa, it is the system that determines that!

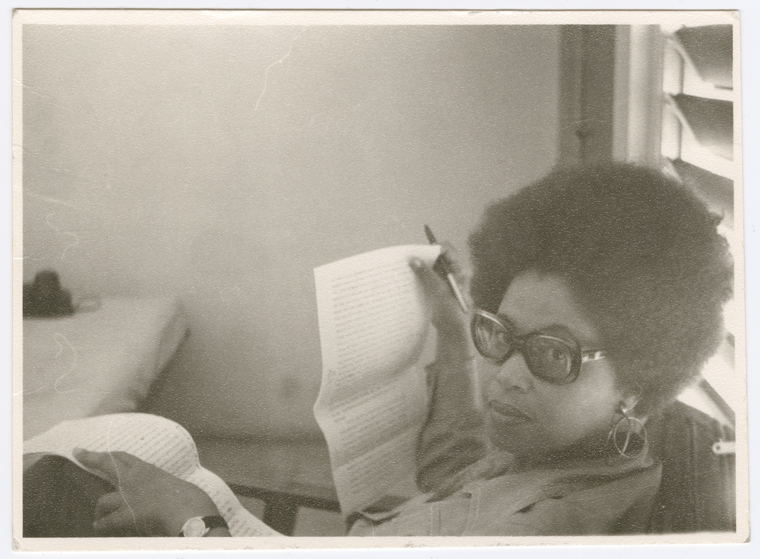

BA: I’m going to change gears a bit and talk about your experience working in Black Studies (institutionally). What I have always found so important in your writing and ideas, is the fundamental critique of disciplines/disciplinarity that you offer. When our group was sorting through your papers, we noticed all the readers and conceptual notes from those years in the 1970s when Black Studies departments were crystallizing, and how wonderfully creative your course readers and syllabi were. Can you share some reflections on these early conversations re: Black Studies, formally in US universities?

SW: When you ask me what the universities thought about Black studies back then, I will tell you that nobody even thought about it! (laughs). It’s that simple. We were starting from a negation on the part of the institution, but I had come with all the knowledge and language I had developed on the creative side of the Jamaica Journal! I did not enter these conversations concerning Black studies with the institution in mind, but rather with the Jamaica Journal’s practice of enacting an autonomous space for transformation, and I had always viewed Black studies as a way of trying to enact a transformation of knowledge, and we did go pretty far at it! But this is of course not how the institution saw it. Black studies was a way of figuring out how to enact a kind of knowledge transformation! I was carrying on the work of the Jamaica Journal, not carrying out the work of the institution you see. And this is where the potential of Black studies was! Language is the way that we will carry ourselves out of these problems we have—that is what is important now to remember about Black studies during those early years, that it was one part of a bigger project of developing a transformation of knowledge and therefore the transformation of the whole of society, by using a different language to address these intellectual concerns.

Now if we once again use the language of the virus, we can see that yes, we are one species, so the differences we see are a result of a system, are the result of an imposition of language, and that is where the transformation must be made and achieved. The only cure will be a transformation of the whole society, and an entirely new knowledge order altogether—otherwise we will remain trapped in this. It is through language that you and I are able to now sit and talk with each other, develop a mechanism to understand one another, do you see the immense potential there?! Language is entirely the point!

Bedour Alagraa is a Professor of Black Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. She is currently working on her manuscript entitled, The Interminable Catastrophe, and is the co-editor, alongside Anthony Bogues, of the Black Critique book series at Pluto Press.