Over 450 Coloradans died of fentanyl poisoning or overdoses just through August of this year, according to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. That number could be on the low end though, as toxicology testing and investigations sometimes take months, CDPHE statistician, Kirk Bol, says

For the first time in three years, the number of fentanyl-involved overdose deaths in the state plateaued, signaling hope for families, law enforcement and government health agencies that Coloradans are taking precautions in the wake of the drug’s deadly societal infiltration.

But the magnitude of the crisis remains staggering.

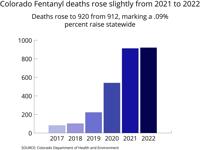

Numbers obtained by The Denver Gazette from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment show 920 people in the state died from fentanyl poisoning in 2022, up .09% from the 2021, when 912 people lost their lives.

Fentanyl rose in popularity because of its potency, lower cost and availability.

"Fentanyl has all but replaced heroin," said Sam Bourdon, manager for the agency's Harm Reduction Grant Fund, which focuses on financial support to programs that aim to prevent overdose deaths and reduce health risks associated with drug use.

Just three years ago, fentanyl was an unknown to many people. It didn’t start appearing on the Colorado scene as an illicit drug until 2017.

Though the drug remains an incredible problem, this small bump is an improvement compared to the precipitous spikes in fentanyl-involved overdoses seen in years before. For instance, deaths from fentanyl-involved poisonings jumped 69% between 2020 and 2021 — from 540 to 912.

But fentanyl overdose deaths made their most concerning leap when fentanyl-involved overdose deaths more than doubled from 222 in 2019 to 540 in 2020, a 143% increase.

Deaths from the pills known on the street as “blues” remain high as compared to other illicit street drugs, such as methamphetamine and heroin, which both saw decreases.

Overall, overdose deaths in Colorado also went down in 2022 — from 1,881 in 2021 to 1,799 last year.

Alcohol poisoning deaths across the state held steady at 60, the same number as the year before.

Compared to other states, Colorado lies toward the bottom of the pack when it comes to fentanyl-involved overdose deaths in 2021, the most recent year for such a data release. Among the 31 states and Washington D.C. which reported their findings to the Centers for Disease Control in 2021, Colorado sat at 22nd, according Bourdon.

National numbers for 2022 won’t come out until later this summer.

Fentanyl is usually transported into Colorado by arterial highways, such as I70 and I25. For that reason and the fact that demand is more urgent in urban areas, many of the rural regions of Colorado, including Kiowa, Jackson, Rio Blanco, Mineral and Gilpin counties, were virtually untouched by total drug overdose fatalities.

Denver, Adams, El Paso, Arapahoe, and Jefferson were top five in order for total drug overdose deaths.

Faces behind the numbers

Christina Luna did not get out of bed on her first Mother’s Day since the death of her 15-year-old Josiah “Joe” Velasquez.

Last year on a sunny May afternoon, Joe kissed Luna goodbye and took off to meet some friends at an Arvada Dairy Queen. A shy boy, he had just been accepted into his big brother Carlos’ circle and he was excited to meet a girl who seemed interested in him.

Sitting by himself on a stool in the DQ lobby while his new crowd milled around outside, he popped a blue pill someone gave him, collapsed, and lay on the ground for 15 minutes before anyone noticed. By the time the EMT’s showed up, it was too late.

“I remember driving to the parking lot and getting in the lobby. I heard them say that he didn’t have a heartbeat,” Luna said.

The high school sophomore was revived, but never regained consciousness.

He was on life support for a week at Children’s Hospital Colorado before Luna made the decision to take him off of life support. She buried him with his favorite Puerto Rico hat.

Joe Velasquez was one of Colorado’s 920 people who died from fentanyl poisoning in 2022.

Luna has started a Facebook group dedicated to other families who have lost a child to the deadly blue pill.

This past Sunday, May 21, marked a year since Joe was taken off of life support. His family and friends honored his short life at his gravesite, which still doesn’t have a headstone because Luna can't afford one. Instead, she brings a large photo of him in the Puerto Rico ball cap and places it at the top of the plot as a substitute.

“I am still in shock," she said. "I find myself in denial.”

She wishes she or someone at the DQ had known about a drug called Narcan. Maybe her son would have had a chance.

Miracle nasal spray

Public health scientists attribute Colorado’ leveling off in terms of fentanyl-involved overdose deaths to public awareness and also to a nasal spray called Naloxone, or Narcan, which they say will soon be offered over-the-counter.

“Most vital to us is getting Naloxone into hands of individuals who use drugs and into the general community. It’s very easy to apply,” said Bourdon. ”I’ve also seen the distribution of test strips, which are used to determine whether fentanyl is present in an illicit drug.”

Bourdon said that though Narcan is available from a pharmacy through insurance for $40-100, it’s been distributed free of charge to public safety organizations, jails, local public health departments, and libraries by the state's Overdose Prevention Unit.

Lots of people have taken advantage of free Narcan handouts.

From fiscal year July 2021 to June 30, 2022, people distributed 124,814 doses. This fiscal year, from July through March, that number more than doubled with 287,814 doses of Narcan given away.

On Tuesday, a McDonald's in Loveland recognized Thompson Valley High School senior William (last name not provided) who saved a someone from overdosing in the bathroom. Last week, he was at the McDonald's at 1809 W. Eisenhower Rd. in Loveland eating dinner "when someone ran out of the bathroom saying a male was passed out and turning purple in the stall."

"William, who is studying to get his EMT, immediately ran to assist the male, administered Narcan and did CPR until first responders arrived on scene and took over," McDonald's stated in a news release. "There is no doubt that the male likely would not have survived had William not stepped up and offered his help."

Bourdon hopes the trend continues and even decreases in 2023, and that fewer Coloradans will die of fentanyl-involved poisonings.

So far this year, the CDPHE reported 223 Coloradans have succumbed to the drug, but that number is not complete for May, as there is a 3-4 month lag in the registration and processing of the death certificate data.

Behind each number is a heartbreak

The loss of Joe at 15 was a horrible kick-off to the destruction of Christina Luna’s family as she knew it.

Consumed with guilt and depression, Joe’s older brother, Carlos, became addicted to fentanyl and has quit school, she said.

Keeping him alive is her greatest struggle, but it’s hard.

Her 18-year-old daughter graduated from high school Tuesday.

The fact that the escalation of fentanyl deaths has slowed in Colorado gives her hope that Joe did not die for nothing.

“Each person isn’t just a statistic. They have families they have their own lives,” said Luna.

A map of where to find Narcan can be found at www.stoptheclockcolorado.org.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices