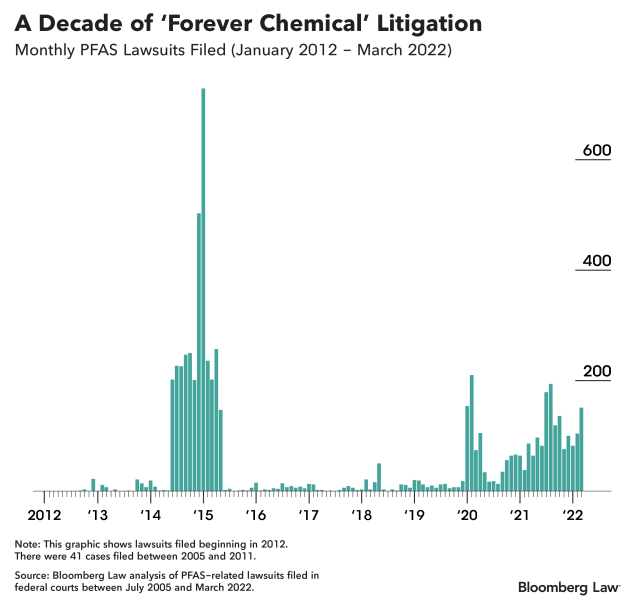

- More than 6,400 PFAS-related lawsuits filed since 2005

- Litigation presents “existential threat” to some companies

For years, plaintiffs’ lawyers suing over health and environmental damage from so called forever chemicals, known collectively as PFAS, focused on one set of deep pockets—

But over the past two years, there’s been a seismic shift in the legal landscape as awareness of PFAS has expanded. Corporations including

If PFAS went into a company’s finished product, odds are it’s being sued. A federal judge overseeing thousands of PFAS cases put the risks bluntly.

“It does not take a genius to figure out that if certain motions don’t go their way, the defendants are in an existential threat to their survival,” Judge Richard Gergel said in a July 2019 proceeding.

E.I. du Pont de Nemours was named as a defendant in more than 6,100 PFAS lawsuits since 2005, the Bloomberg Law analysis found. But no company’s degree of legal jeopardy may be rising faster than 3M’s. It was named in an average of more than three PFAS-related lawsuits a day last year, according to the analysis. The company’s most recent annual report dedicated more than 15 pages to its legal exposure from PFAS.

Total PFAS liabilities could reach $30 billion in a “worst-case scenario” for the company, according to some estimates.

“It’s looking like 3M is going to bear the most liability, if there is any,” Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Holly Froum said. It becomes more apparent as the court splits defendants into the different roles they had in manufacturing PFAS-containing products, she said.

“Some of them only made surfactant and some were the finished product manufacturers. 3M did everything.”

Cost of Durability

Nearly every American has PFAS in their bodies.

Fast food containers, cosmetics, furniture, carpeting, and waterproof jackets are just some of the items that can contain PFAS. The chemicals are also widely used in commercial applications like wiring insulation, personal protective equipment, and medical devices.

PFAS, short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are some of the most durable and water repellent materials ever discovered. Those properties led to their widespread use beginning with PFOA and PFOS—two types of PFAS—in the 1950s. Soon, products made with PFAS like Teflon and Scotchgard were mainstays in many homes.

Today, fluoropolymers—a group of polymers within the larger family of PFAS—are estimated to be a $2 billion-a-year industry. Overall, more than 10,000 chemical substances can be classified as PFAS in the U.S.

The durability that makes PFAS so valuable is also what creates its health risks. The chemicals can’t naturally break down, so they accumulate in water, on soil, and in blood. Studies have shown that high levels of PFAS can lead to increased risk of cancer, changes in liver enzymes, and decreased vaccine response, among other health effects.

Studies at DuPont and 3M as early as 1961 found adverse health effects from PFAS exposure. But it wasn’t until the early 2000s that questions increasingly emerged in public about its safety.

In response, 3M phased out most use of PFOS and PFOA by 2002. E.I. du Pont de Nemours stopped using PFOA in 2015.

Firefighting Foam

In the 1960s, the U.S. Navy worked with 3M to develop firefighting foams that could efficiently fight liquid fuel fires—known as Class B fires. Water can’t be used on these fires because gasoline, which is lighter than water, rises to the surface and continues burning. The intensity of the fires also evaporates water before it can have an effect.

The product 3M and the Navy created was called aqueous film forming foam, or AFFF. It utilized a blend of PFAS—often PFOS—and water to create a foam that can blanket a liquid fuel fire and suffocate it. The foam also prevents hot fuel from reigniting.

The product has been required at military bases and airports for decades. But its frequent use in training exercises and emergencies has elevated PFAS levels in surrounding groundwater and drinking water. The water authority near Delaware’s Dover Air Force Base, for example, reported in 2018 that its drinking water had PFOS and PFOA levels 2,435 times greater than the EPA’s health advisory level—likely due to the use of AFFF.

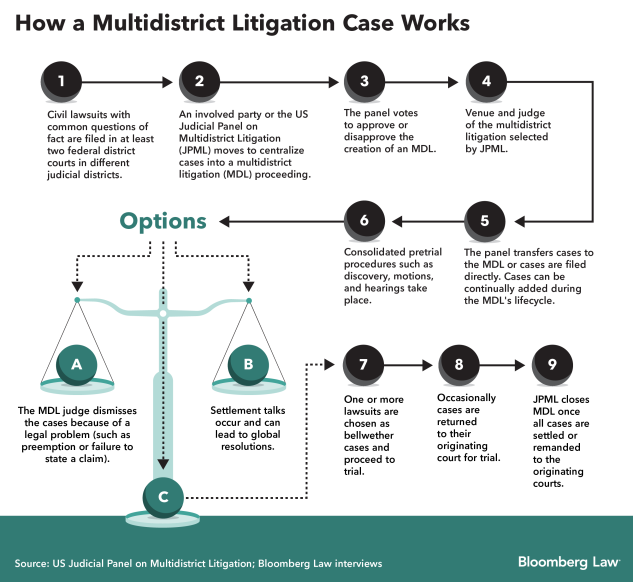

These firefighting foams are now the source of so much PFAS litigation that in late 2018 a special body within the federal judiciary consolidated hundreds of cases into a single docket called a multidistrict litigation.

At least 1,235 PFAS lawsuits were filed in 2021, according to Bloomberg Law’s analysis, and more than 97% ended up in the AFFF MDL overseen by Gergel in the U.S. District Court for the District of South Carolina. The MDL has become so complex that, over three years, more than 3.5 million documents have been produced in discovery, according to court records.

“Plaintiff lawyers tend to piggyback, so the more attention, the more potential liability,” said Matthew G. Jeweler, an attorney at Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP who specializes in insurance coverage disputes.

The creation of an MDL may have spurred some of the change in litigation strategy.

“That’s a big criticism of MDLs,” said Robert Klonoff, a professor at Lewis & Clark Law School and author of a book on multidistrict litigation. “They say once an MDL is filed, everybody flocks to it and people file suit. And there are arguments that people file suit without having the evidentiary basis for the claims and they all get thrown in without any scrutiny. There are a lot of criticisms in that regard that in some ways it stimulates more cases.”

It’s not the first MDL formed to address PFAS cases. At least two others were created—one to address Teflon lawsuits in 2006 and one focused on personal injury litigation against E.I. du Pont de Nemours in 2013.

Dark Waters

The majority of PFAS cases that Bloomberg Law identified—57.7%—were filed as part of the 2013 personal injury litigation. Those cases focused on contamination at DuPont’s Washington Works facility in Parkersburg, W. Va., which is now owned by Chemours. The plant was the focus of the films Dark Waters and The Devil We Know.

But while both of those MDLs focused solely on DuPont and its successor companies, the variety of plaintiffs and the scope of the companies they’re suing is much broader in the South Carolina MDL.

Plaintiffs’ co-lead counsel Michael A. London said at a summer 2021 PFAS conference that the types of claims in the firefighting foam MDL fall into one of five categories:

- Personal injury claims;

- water provider claims from utilities that must pay for cleanup of PFAS in drinking water;

- property diminution of value claims, especially by airport where the ground is now contaminated;

- claims by state attorneys general with natural resource damage cases, especially with fishing or hunting;

- medical monitoring cases.

The biggest question is what manufacturers knew about the dangers of PFAS and when they knew it, according to Paul Napoli, one of the plaintiffs’ co-lead counsels in the firefighting MDL.

“The deeper you dig, the more insidious it is—the more you learn how much these companies, these manufacturers knew about their potential health concerns and the actual health concerns,” Napoli said.

WATCH: PFAS: The ‘Forever Chemicals’

Standing by Products

Manufacturers deny many of the claims raised in recent lawsuits and stand by their environmental records and their products.

3M has contributed more than $1 billion to PFAS remediation and environmental projects, spokesman Sean Lynch said.

“3M acted responsibly in connection with products containing PFAS, including aqueous film forming foam (AFFF), and will vigorously defend our record of environmental stewardship,” Lynch said in an email.

Chemours, when reached by email, declined to comment on its ongoing litigation. However, the company said it has never made or sold PFOS—the type of PFAS that’s present in many types of firefighting foams.

Chemours spokeswoman Cassie Olszewski said that the company’s chemistry work enables essential functions in clean energy, advanced electronics, and other product segments to function.

“With respect to many of the most critical applications that depend on fluoropolymers, especially those that require high-speed, high volume transmission of data, miniaturization, or extremes in temperature, there are currently no viable alternatives to fluoropolymers,” Olszewski said in a written statement.

A representative for DuPont de Nemours stressed the separation of the current company known as DuPont from its predecessor E.I. du Pont de Nemours (EID).

EID’s chemical business and its fluorochemicals line was spun off into Chemours in 2015. EID subsequently merged with Dow Chemical Co. to create DowDuPont in 2017 but by 2019 the company spun off its materials science business to Dow Inc., its specialty products business to Dupont de Nemours, and the remainder of EID including the agriculture business became Corteva.

Chemours sued DowDuPont in 2019, alleging that the company offloaded potentially unlimited environmental liabilities in the spin-off. Chemours, DuPont, and Corteva reached a settlement in January 2021 that includes a $4 billion cost sharing arrangement for PFAS liabilities.

Corteva declined to comment for the story.

DuPont de Nemours is now focused on the specialty products market and not involved in production of fluoropolymers, according to company spokesman Daniel Turner.

“DuPont de Nemours has never manufactured PFOA, PFOS or firefighting foam,” Turner said in an emailed statement. “While we don’t comment on pending litigation, we believe the complaints are without merit, and are examples of DuPont de Nemours being improperly named in litigation. We look forward to vigorously defending our record of safety, health and environmental stewardship.”

Struggling to Pay

The companies being sued are largely relying on the “government contractor” defense—which the Supreme Court recognized in 1988 as limiting manufacturers’ liability when producing military products to government specifications.

“The majority of the foam at issue is specified and used by the U.S. government and military, and therefore, subject to the government contractor defense,” CEO George Oliver said.

But the defense hasn’t been applied to PFAS producers. The court in South Carolina is currently weighing whether companies can use the defense for many of the pending MDL claims, and that ruling could be the deciding factor in billions of dollars worth of cases. A ruling is expected as soon as this summer.

Even if the defense can be applied to PFAS lawsuits, it likely wouldn’t apply to many of the cases which don’t involve military bases, multiple lawyers told Bloomberg Law. Adding to uncertainty is a recent decision in a Georgia case where a federal judge dismissed claims against primary manufacturers of PFAS but not secondary manufacturers that treated carpets with PFAS.

A spokeswoman for Johnson Controls declined to comment.

Once the ruling on the contractor defense is out, three cases are on the shortlist to serve as bellwether trials in the AFFF MDL. All involve utilities alleging that PFAS manufacturers contaminated drinking water.

Those cases are “in some ways like the canary in the coal mine,” according to Gergel.

The water providers don’t have to prove individual customers are injured, so if they can’t win their cases, it could spell trouble for the other claims that require even more complex legal arguments, the judge said in a July 2019 status conference. A bellwether trial could take place as early as the first quarter of 2023.

Anaheim, Calif., is one of those local governments suing 3M, DuPont, and other companies for PFAS contamination that prompted it to shut down contaminated water sources and implement cleanup. It’s spending $150 million to construct a new water treatment program and $1.5 million a month to ship in non-contaminated water until a decontamination facility is complete. Anaheim raised water rates while promising customers it’d go after PFAS polluters to recover the cost of the clean-up.

“They didn’t create this problem,” Anaheim’s water engineering manager Michael Moore said of his city’s water customers. “This wasn’t even here in Anaheim. It was created outside of the area and worked its way here. They shouldn’t have to bear the responsibility for that.”

Data reporter Jasmine Han contributed to this article and graphics.

To contact the reporter on this story:

To contact the editors responsible for this story:

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

Learn About Bloomberg Law

AI-powered legal analytics, workflow tools and premium legal & business news.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools.