About this project: Amid Breonna Taylor protests in Louisville, Imani Smith — a Centre College student and president of the board of directors for the Youth Resistance Collective — came to The Courier Journal with an idea to share the stories of other young activists leading the fight for racial justice. The following profiles are her work, edited by reporter Bailey Loosemore and editor Veda Morgan.

Correction: A previous version of this article misrepresented Travis Nagdy's time in foster care. Nagdy spent two years in foster care and returned to living with his mother at 16.

Growing up in Louisville, I’ve heard the inspiring and challenging stories of young, Black people working toward “what’s possible."

My father, the late Rev. Gregory F. Smith was one of those young folks — sharing his story with me and his congregation about using his voice as a young minister and being fortunate to have a community willing to listen.

It's stories like his that have taught me about the rich, long heritage of young, brilliant, forward-thinking leaders who have sprouted here.

For the past two years, I have been given the opportunity to work with some of those brilliant leaders, doing everything from sitting in Metro Hall analyzing policies to marching in the streets demanding justice for Breonna Taylor.

So many of us are fighting for a more equitable system, a chance to be seen as human beings. Fighting to win the respect, opportunities and better means of life often expected by our white counterparts.

The truth is, we are in the fight of our lives against a system that from birth marks some for success and others for mistreatment, just because of the hue of our skin.

The individuals featured in this story embody those values at an age younger than most who sit at decision-making tables.

These are their stories of how they came to be in the fight, why they do what they do and where they hope to lead us.

Listen, learn and lead.

MALIYA HOMER

Age: 20

Maliya Homer stepped up to the microphone, written speech in hand, nervous about the words she planned to speak but confident they needed to be heard.

Before her were attendees of a memorial for Breonna Taylor, hosted by the University of Louisville. Behind her was the school’s president, Neeli Bendapudi — who Homer was about to confront.

“Let me begin by saying that I do not speak for all Black people, for all campus (organizations) or all Black students,” Homer said. “Our Black experience is not a monolith, as we have to keep reiterating.”

But as president of the U of L Black Student Union, Homer had been asked to represent her peers. And she felt a few points needed to be made in front of the school’s administration, whom the union had been pushing to end its relationship with the Louisville Metro Police Department.

“What are we supposed to do... when we raise these issues to university leadership, (and) we are served with exactly what we didn’t want: panels, platitudes, performance efforts and the promise of trainings" that teach law enforcement "not to kill us."

Homer’s speech in October exemplified the role she’s cultivated for years in the local movement for Black liberation: being a voice for her peers and articulating how so many of them feel.

It’s a role the Lexington native began to take on following the death of Trinity Gay, a 15-year-old local track star and daughter of Olympic runner Tyson Gay who was shot and killed in a gunfight between four men at a restaurant in 2016.

Two years later, while at Lafayette High School, Homer found herself addressing the same issue of gun violence in the wake of the Parkland, Florida, school shooting, which weighed on many young minds.

To draw attention to the need for change, Homer and a group of classmates organized a school walkout and held a public town hall with local and state politicians.

Now, as a junior and Pan-African studies major at U of L, Homer said she feels it’s her responsibility to use the information she’s learned in her courses to continue pushing for progress.

“I want to build a better world,” she said. “... I really want it to be a world where Black queer youth don’t have to experience all of the same things that I had to experience, that many people that came before me had to experience.”

“My call to action is to listen to the kids, listen to the children, listen to what kind of insight that we have to provide and work to build a new world.”

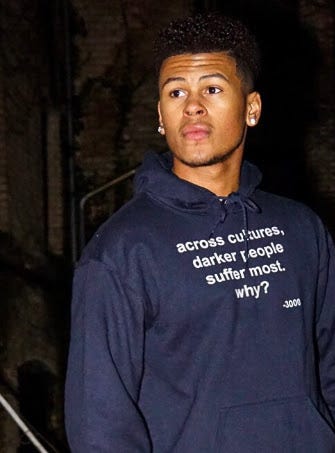

SEAN ALI WADDELL

Age: 19

Sean Ali Waddell doesn’t claim to be an activist.

But after he delivered a powerful speech on the steps of the Kentucky Capitol last summer, where he called on Sen. Mitch McConnell and Attorney General Daniel Cameron to bring justice for Breonna Taylor, Waddell showed he’s earned the title.

“I know that we, as a people, are strong and beautiful,” Waddell said in an interview, “and we deserve what anyone else deserves. Anytime I see us being walked over, our lives being disregarded, you know, I can’t allow my people to just be treated any type of way and it not affect me.”

Waddell is well-known locally for his connection to another Louisville activist: his late cousin, "the Greatest," Muhammad Ali.

But in the wake of Taylor’s death, the Howard University sophomore has come further into his own voice, rendering his community’s feelings through music.

“Twenty-twenty my people still wiggling out that noose,” he rapped in his debut song. “I’ve been speaking from my heart all summer, nothin’ but the truth.”

Waddell said his commitment to his community stems from his family roots, subscribing to Ali’s outlook that service is a responsibility, not an elective.

And he sees his role in Louisville’s movement as promoting one resounding message: That his community can shine and have confidence, even in heartache.

“I want to see us uplifted,” he said.

Waddell said he also draws inspiration from figures like Marvin Gaye, whose famous question of “what’s going on” still connects with today's experience.

“I want to see our society finally address the root of what’s happening here along the lines of race,” Waddell said. “It’s going to continue to pop up until we address (it).”

Despite the strain of seeing what’s happening around him, Waddell said he has hope and is proud of the diverse support for the current racial justice movement.

His call to action: “Find your reason and get in your lane. Authentically be yourself and make a change at the same time.”

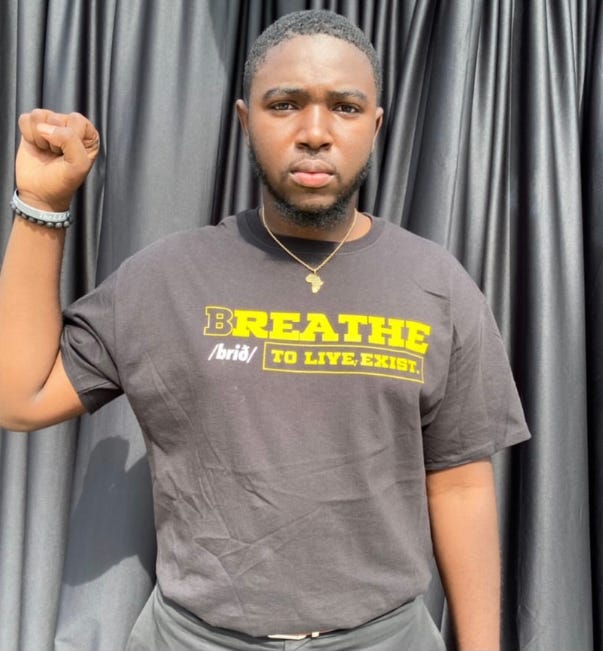

SAVION BRIGGS

Age: 19

Savion Briggs hadn’t even graduated eighth grade when he first felt called to be an activist.

Now 19, Briggs had grown up learning the stories of Trayvon Martin and Tamir Rice, two Black teens who were shot and killed in 2012 and 2014, respectively, one while walking home from a convenience store and the other while playing with a toy gun in a park.

And he said he’d realized, through using art as a release, how much their identities matched his own: that of a Black teen society often overlooks or misjudges.

The realization made Briggs feel “like it was my calling to be a voice for my people,” he said, drawing on the words of his favorite revolutionary, Fred Hampton, a deputy chairman of the national Black Panther Party who was targeted and assassinated in 1969.

Briggs has since used his voice to call for racial justice, working to create change through the Black Student Union at Butler High School.

"I started really figuring out how I can actually put hands on the ground and actually get active," he said.

Now the freshman class president at Kentucky State University, Briggs recently channeled his energy into fighting against police brutality by leading marches at Breonna Taylor protests and helping establish the youth collective Are We Next?, which prepares peers to demonstrate safely.

Briggs said witnessing pain in his community led him to develop “a natural fear of the police.” And after watching Louisville officers set off tear gas and aggressively arrest protesters last summer, Briggs said he felt compelled to equip others with knowledge that could prevent them from getting hurt.

He has also worked with other community organizations, such as the Youth Resistance Collective and Books and Breakfast Louisville, a group dedicated to enriching minds and bellies through breakfast and discussions of books by Black authors.

Briggs hinted at one day running for office, following in the footsteps of inspirational people like former Kentucky Rep. Charles Booker, who earned national acclaim during his 2020 U.S. Senate campaign.

When talking about, his experiences and challenges of the past year, Briggs stressed the importance of knowing yourself — a call sent specifically to the Black community.

To help inspire the next generation of change-makers, Briggs said he brings younger family members to marches and works to build up student action groups, such as KSU’s W.O.K.E. Task Force.

“It’s just about keeping the pedal to the metal,” he said.

ASHANTI SCOTT

Age: 20

Ashanti Scott was just 15 when she won her first policy change.

Then a sophomore at Butler Traditional High School, Scott said she realized the school’s new anti-natural-hair policies discriminated against Black students, preventing them from having hairstyles like locs and braids.

And with the help of her mother, State Rep. Attica Scott, she launched a social media campaign, calling on the school’s site-based decision-making council to revoke the restrictions.

“For too long, discrimination in public spaces have targeted the kinks, coils, locs and waves of Black and brown heads,” Scott later wrote in an opinion piece. “For too long, young ladies and gentlemen of color have been told our hair was ‘unruly’ or ‘unkept’ or ‘unprofessional’ and most offensively ‘unwelcome.’”

Within days of raising the issue, Scott said, the council overturned the policy.

Today, Scott is 20, and her advocacy is centered around supporting the Breonna Taylor movement and pushing to protect Black residents through legislation such as Breonna’s Law, a bill filed by her mother that would ban no-knock search warrants statewide.

“The inspiration behind my activism 100% goes to my mom... who has always brought me along to community events, who has always shown me the importance of showing up for my community,” Scott said

Last summer, Scott and her mother were frequent visitors at Jefferson Square Park (known in local activism circles as Injustice Square), which protesters occupied for more than 150 days.

On Sept. 24, she was arrested with her mother and other local activists on felony rioting charges, which were dismissed on Oct. 6 because there was no evidence they participated in "tumultuous and violent conduct." In the months since, Scott has organized rallies and sat on panels, bringing light to the injustices she felt the night of her arrest.

Last month, she testified in Frankfort against House Bill 479, legislation that would expand the attorney general’s powers and allow him to charge people with protest-related crimes.

Scott said there’s more work to do when it comes to making society’s systems more equitable.

Stopping the progression of gentrification in majority Black neighborhoods and making voting more accessible to people of color are two of her top priorities.

She said she’s seen progress in the widespread use of mail-in voting in the 2020 elections, and she hopes recent changes set a precedent that will lead to automatic voter registration.

As she continues to push for change, however, Scott said justice for Taylor should continue to stay at the top of everyone’s minds.

“Share the flyers; make sure we keep (Breonna) Taylor’s name trending, because we haven’t gotten justice and we’re still fighting,” she said.

QUINCY ROBINSON

Age: 21

Quincy Robinson believes a community must strive for three things if it wants to achieve the change it desires: accountability, consistency and progress.

At 21, Robinson is already leading by example, showing others what steady, dedicated involvement looks like.

He’s everywhere when it comes to community organizing. Calling himself “the feet,” Robinson spent last summer working with several social justice groups — including Black Lives Matter Louisville, the Youth Resistance Collective, the Youth Violence Prevention Research Center and Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity Inc. — to conduct community education trainings and lead protests.

His end goal is “the collective liberation of Black and Brown people” — a daunting task that would take a toll on most. But Robinson has no plans to stop working toward it anytime soon.

“My hopes for the future are a world where everyone’s right to be alive is recognized and guaranteed and sustained,” he said.

Robinson said he joined the protests because he “started becoming more and more aware of the social problems” that plague Louisville’s Black residents and felt like he “should do something to help fix them.”

The top issues that come to his mind: “police violence, voting discrimination, poverty and food and housing insecurity.”

For him, the crucial steps in achieving a just future are educating and mobilizing people to work inside and outside society’s systems, winning elected offices and teaching community members about policies that can improve racial equity.

“Every young person has a passion, and their collective energy can be focused on changing the structure of our society in such a way that eradicates systemic violence,” Robinson said. “Within Louisville, it looks like networking and working together to take big, bold action."

NAZE AFENI

Age: 21

Naze Afeni remembers how difficult it was to find confidence and identity as a Black, non-binary teen navigating a society that didn’t afford the same learning opportunities or space to make mistakes as it did their white peers.

But over the summer, like many young activists, Afeni said they found their voice while calling for justice for Breonna Taylor.

Now 21, Afeni has drawn on their heritage and their family members’ roots in activism to become an activist in their own right, finding solace and self in a community that accepts them.

“I organize because my ancestors brought me here, honestly, and if I don’t do it, then nobody else will,” Afeni said.

Afeni’s story mirrors those of others who’ve shown the resilience and determination of Blackness, through the ages. And it’s brought them into the ongoing fight for Black liberation — a goal that involves helping people achieve autonomy over their lives so they can topple oppression.

Afeni is coming into their own, building on their experience of watching their cousin, Chanelle Helm, an organizer with Black Lives Matter Louisville. And they’ve taken on roles in various social justice organizations that are working toward the same outcomes.

Afeni says no one knows what the future holds, not for ourselves or for our country. But they hope the things the Black community has already accomplished, such as greater cultural and political consciousness and resourceful connectivity, can be passed on and improved by the next generation.

“I hope that we can prepare them for the things that are coming their way,” Afeni said. “I hope that we can grow into this future unified and dismantling the systems that do oppress us.”

Afeni said to achieve liberation, people must build power, confidence and resources that benefit the Black community, and everyone must play their part of the movement by educating others and creating more equitable laws and policies.

“Get involved in your community, hold your community accountable, hold your peers accountable,” Afeni said.

That’s how the Black community has won battles throughout history, and it’s how the movement will continue to make progress now.

AUBRI STEVENSON

Age: 18

Aubri Stevenson is tired of living in fear.

That’s why she joined the movement for racial equity, educating herself as a student at Manual High School before stepping into leadership positions as a freshman at the University of Louisville.

“I want to live in a community where I feel safe,” she said. “I want to live in a world where I feel safe, where I feel free to be able to express who I am, not being afraid to walk down the street due to the fact that I am a different skin tone, that I am a different color.”

This summer, while helping establish the Youth Resistance Collective, Stevenson said she began to fully understand what it means to be an activist, especially as a young Black woman reeling from the death of another Black woman.

Though she had served as vice president of Manual’s Black Student Union and had participated in community organizing, Stevenson said Taylor’s death opened her eyes to the injustices faced by Black women, specifically.

Over the last year, she’s stepped up to claim and show her power, taking on roles where change can be made, including as ambassador of the U of L Black Student Union, and fighting to make her voice heard in often male-dominated spaces.

“Whatever I need to do, whether or not that’s protesting or conducting policy change with other youth organizers... whatever I’m able to do at this age... is what I’m gonna do,” Stevenson said.

Activism, to Stevenson, is so much more than just the changing of a few faces in seats of power.

Stevenson wants to work toward solutions that will ultimately bring justice and peace to her community.

“We have seen that with the people who have been in power for these past four years, we've seen what they've done,” Stevenson said. “We've seen how this country has turned; we’ve seen how this country has divided. That’s something I wish to not see continue.”

JAIDA HAMPTON

Age: 22

Jaida Hampton looks at the young activists involved in the movement for racial justice and sees the country’s next great leaders.

“My hope for the future is to see the next Rosa Parks being brought up,” she said.

But to become a leader, youth need resources.

That’s where Hampton comes in.

Hampton is president of the Kentucky NAACP State Conference Youth & College. The recent University of Kentucky graduate relocated to Kentucky from Chicago for college, wanting to help change the dynamic for Black students on a predominantly white institution campus.

Now, her main goal is to connect young activists with tools they need to create sustainable change, such as free political organizing training — staples of social justice movements throughout history.

Focusing on educating “ourselves so we can go back and educate our community” is Hampton’s way of strengthening herself and her peers.

Hampton has done just that by interning with U.S. Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee in Houston, where she learned just how connected the criminal justice and education systems are.

And over the past year, Hampton has brought that knowledge to communities across Kentucky, where she and others are fighting for justice in the Taylor case.

Hampton said she hopes the resources built during the current movement remain for a long time to come.

“The youth are often overlooked and lack the support we need to keep us motivated in the fight by those we look up to for leadership in our communities," she said. "I believe that Louisville will begin to see a drastic change in policy and resources such as food security, housing and public education for its community members because of the fight coming from youth leaders."

HAMZA ‘TRAVIS’ NAGDY

Age: 21

Travis Nagdy — known for his special combination of a smile, afro and bullhorn — was one of the most constant figures at last summer’s protests.

It was normal to see him weaving excitedly through the crowd, leading chants and handing out food at Jefferson Square Park, the protesters’ home base in the center of downtown.

“Travis was one of the only movement leaders that stayed on the path of peace," said friend Cheyenne Osuala. "He was gentle and loving, and cared a lot about people. He even took in a homeless kid into his home for a couple of months during the movement."

On Nov. 23, the 21-year-old’s life was cut short when he was shot and killed during an alleged carjacking.

But the time he spent demonstrating left a major impression on other young activists who’ve promised to continue carrying his message to “keep going” in his name.

A month before his death, Nagdy sat down for a late-night Zoom call, tired from a long trip across the state spent building up the movement but ready to share his story.

It started as a child who spent two years in the state’s foster care system, which forced him to leave his hometown of Louisville and move from county to county in south central Kentucky.

Nagdy returned to living with his mother, Christina Moynagh, at age 16. But he said he found himself struggling to break bad habits he’d developed within the system.

It wasn’t until roughly a year and a half ago that Nagdy committed to becoming the version of himself that he wanted to be, a goal that involved using his experiences within the system to help change it.

Nagdy found support and a similar drive in other activists at the Taylor protests, and he began attending political organizing meetings and joining new organizations, such as No Justice No Peace, Black Lives Matter Louisville and Until Freedom.

Nagdy said through the groups, he began to learn how changemakers operate, and he set his sights on how to make change happen.

Before his death, Nagdy said he wanted to start his own organization called Keep Going, which would offer peer mentoring for young adults between 18 and 24 years old and carry his mission beyond the summer’s marches and demonstrations.

Nagdy had already begun to deepen his service within the community by joining in efforts to aid the homeless and participating in discussions about reducing gun violence.

“We get that it takes a lot more behind the scenes” to change racial inequities, Nagdy said. “Don’t think that we’re not taking that seriously. ...We’re going to be doing whatever community outreach it takes.”

For him, that included reaching beyond Louisville to build a community organizing network between Black communities across the commonwealth.

Nagdy’s hope was for people statewide to “keep showing up and supporting” community efforts that could sustain real, long-term change.

In essence, to “keep going.”