New York’s top hospital executives and doctors received millions of dollars in salaries, bonuses and other perks as federal pandemic relief funds flowed to their hospitals that faced plunging patient revenues during the initial COVID-19 waves in 2020.

As many frontline health workers desperately fought for more personal protective gear and improved staffing levels, some hospitals continued to use seven-figure payouts to drive executives to hit profit and performance goals, USA TODAY Network New York found.

Bonuses totaling about $73 million went to 268 hospital officials in the Hudson Valley, Finger Lakes, Southern Tier, Mohawk Valley and other communities across the state in 2020 alone, the most recent federal records show. That is an average bonus of about $273,000, keeping pace with executive payouts that spiked in the four years before the pandemic hit.

Much of the bonus money flowed to leaders of New York’s most politically powerful hospital networks, which also received the biggest shares of the $6 billion provided to New York health providers through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, also known as the CARES Act, in 2020.

While the Trump administration and lawmakers at the time described the aid as crucial to shoring up patient care, the initial waves of taxpayer funds came with no strings attached.

So as reports of ventilator shortages and freezer trucks filled with bodies of COVID-19 victims dominated the news, hospitals were quietly allowed to use emergency relief funds however they wanted, rather than being directed to spend it on patient care.

Ultimately, dozens of hospitals in New York went on to pay out millions in executive bonuses and record profits for the year, federal records show, an outcome that has advocates and government watchdogs pushing to ensure that in the future, federal funding won't play a role in padding executives' pockets during a global emergency.

“The next time Congress wants to give out money, it needs to think about what it’s being spent on,” said Eileen Appelbaum, the Center for Economic and Policy Research co-director.

All future emergency aid, she added, should include bans on executive bonuses, acquisitions, and other spending unrelated to patient care.

What New York hospitals say about executive pay

Yet hospital trade groups in New York described the executive payouts as a necessity of American medicine, as hospital networks across the country compete to attract and retain top talent.

The groups, which represent many hospitals across New York, also asserted payouts are linked to the complex demands on executives who run sophisticated hospitals that never close and employ thousands of people.

“Running a hospital or health system is extremely challenging in the best of times, and during the COVID-19 pandemic the challenges were monumental, including significant shortages of supplies, equipment, and our outstanding health care workers,” Brian Conway, a Greater New York Hospital Association spokesman said in a statement.

Conway’s group and another hospital trade group, Healthcare Association of New York State, both declined interview requests regarding the connections between CARES Act funding and executive compensation.

Amid the heated debate, the USA TODAY Network New York analysis of hospital financial records revealed new details about the contrast between executive payouts and frontline workers’ struggles during the pandemic’s darkest days.

Further, the executive bonuses in 2020 underscored the history of questionable financial dealings of some New York nonprofit hospitals that reaped tax exemptions stateside but also invested in murky offshore accounts catering to corporate giants and criminal elements alike.

Meanwhile, clashes between labor unions and hospitals have exploded since 2020, as frontline medical workers demand higher wages, benefits and staffing levels, citing the crushing workloads and trauma they endured during the pandemic.

What follows are details of the top payouts at more than 40 hospitals and health systems spread across the state, as well as frontline workers’ accounts of their pandemic-related suffering, perseverance, and frustration with organizational inequality in the health care industry.

What a nurse says about New York hospital executive pay

The news of bonuses paid to health system executives in 2020 felt like a slap across the face for nurse Margaret Franks.

The sting hit, she said, because those same leaders at Nuvance Health, her employer, offered limited acknowledgement — financial or otherwise — of the sacrifices she and fellow nurses made in the pandemic’s first year.

“When I was in those COVID ICUs, it was just nurses in the room with the patients,” Franks said.

That was probably the worst part of the pandemic: We were seeing death on a level we hadn’t really experienced before.

“Administrators got to work from home or got to walk around in the hallways where the patient care wasn’t going on,” she added, “but we had no choice.”

Now, Franks is spearheading her New York State Nurses Association union’s push for a new contract. The effort aims to improve pay rates and staff-to-patient ratios to reflect the pandemic burden shouldered by nurses at Vassar Brothers Medical Center in Poughkeepsie, she said.

Yet Franks, a 53-year-old former pastry cook who became a nurse in 2014 in part to help patients, struggled to describe what she felt nurses deserved for bracing New York’s health system against the historic global pandemic.

She tried to measure the toll in her emotional and physical scars.

Franks recalled looking into the mirror daily, wincing at the sight of deep red lines and rough skin across her face due to the ravages of wearing an N-95 mask over her 12-hour shifts.

Memories resurfaced of her care for dying COVID-19 patients on ventilators — a waking nightmare filled with haunting sounds of breathing machines and family members sobbing as they said goodbye virtually amid the pale blue glow of digital tablets.

“That was probably the worst part of the pandemic,” Franks said. “We were seeing death on a level we hadn’t really experienced before.”

She described constantly being thirsty at work thanks to a cruel pandemic catch-22: Her body drenched in sweat underneath double layers of gloves and gowns, while she feared drinking too much water to avoid repeatedly donning and doffing the protective gear to use the restroom.

It’s definitely nice to be acknowledged, and nice to know somebody is willing to say so means a lot because we’re not getting it from the people who should be doing it.

She also recounted facing harrowing isolation during the two months she spent living in a hotel to limit the risk of bringing the virus home to infect her family. The small stipend from the hospital covering most of the hotel stay costs, she added, stood as one of the few recognitions of her pandemic sacrifices.

But for Franks — whose salary was $98,000 after receiving contracted 2.5% raises each year during the pandemic — the fact state government is now providing up to $3,000 in pandemic payments to eligible health workers represented a stark contrast to her employer’s response.

“It’s definitely nice to be acknowledged,” she said, “and nice to know somebody is willing to say so means a lot because we’re not getting it from the people who should be doing it.”

Nuvance Health declined an interview request and issued a statement in response to questions for this report.

“All Nuvance Health compensation is commensurate with experience and industry pay to ensure we can attract and retain the highest quality staff," spokesman John Nelson said in the statement.

"This extends to physicians, clinical staff, administrative staff, and leadership," he added, noting Nuvance Health adjusts "salaries on an ongoing basis to ensure every member of our team is compensated appropriately.”

How did COVID pandemic aid flow to hospitals?

The 2020 hospital payouts followed years of large health networks taking over smaller hospitals, consolidating wealth in spite of hardships facing some patients, frontline workers and smaller community health care facilities.

The trend has been part of an arms race among top hospitals to offer Wall Street-style bonuses, severances and retirement perks, suggesting efforts to cut health care spending through consolidation missed some executive suites.

One wave of rising payouts came in the wake of key Affordable Care Act reforms between 2014 and 2016, a span when hospitals collected billions in revenue as federal subsidies and consolidation incentives boosted bottom lines.

But when the pandemic hit in 2020, many hospitals faced dire financial losses due to non-COVID-19 patient care — and revenue — plummeting amid lockdowns and coronavirus fears.

Trump and federal lawmakers promptly approved the CARES Act in late March to provide emergency funding to hospitals across the country.

The measure soon drew criticism from advocates and government watchdogs, however, for allowing regulators to devise rules that funneled much of the $178 billion in aid nationally to large hospitals and health systems, which wield outsized political power through lobbying and general economic clout.

In other words, the federal government bailed out rich hospitals — many of which held large cash reserves and other investments — and provided less aid to smaller community and rural hospitals that needed the money, according to research by Appelbaum, of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, and others.

If you’re so poor because of the pandemic, you need to be consigning all of the money you get to addressing the financial losses and the needs of the patients.

The episode raised questions about the need for financial aid at some hospitals, Appelbaum said recently, and calls for improved oversight of how health care facilities spend government funding.

“If you’re so poor because of the pandemic, you need to be consigning all of the money you get to addressing the financial losses and the needs of the patients,” she said.

Indeed, a limited number of hospitals and health providers nationally, including California-based Kaiser Permanente, decided to return COVID-19 relief aid in 2020, noting they didn't need the money, Appelbaum said. And while later rounds of COVID-19 relief used new rules to get more money to hospitals in need, the efforts never offset the early inequality.

Further, most hospitals in New York and elsewhere ended their 2020 fiscal years in the black after receiving billions in relief from Washington and despite the pandemic’s impact, according to an analysis by the Empire Center, an Albany-based think tank.

Among reports filed by 147 hospitals across the state, 58% showed positive net margins for the year, just below the 59% average of the previous nine years, the center reported.

Now, the USA TODAY Network analysis of federal tax records offered the first look at how much hospitals paid executives and administrators while the taxpayer aid flowed in 2020.

Who are the highest paid New York hospital executives?

The scope of pay packages for top hospital executives and doctors, in some ways, is illustrated in one number: $361 million.

That’s the total compensation paid to 364 hospital officials in 2020. Put another way, the average total pay was nearly $1 million.

Yet pay inequality within the leadership ranks also exists, as an elite group of about 40 executives and doctors received bonuses of at least $500,000.

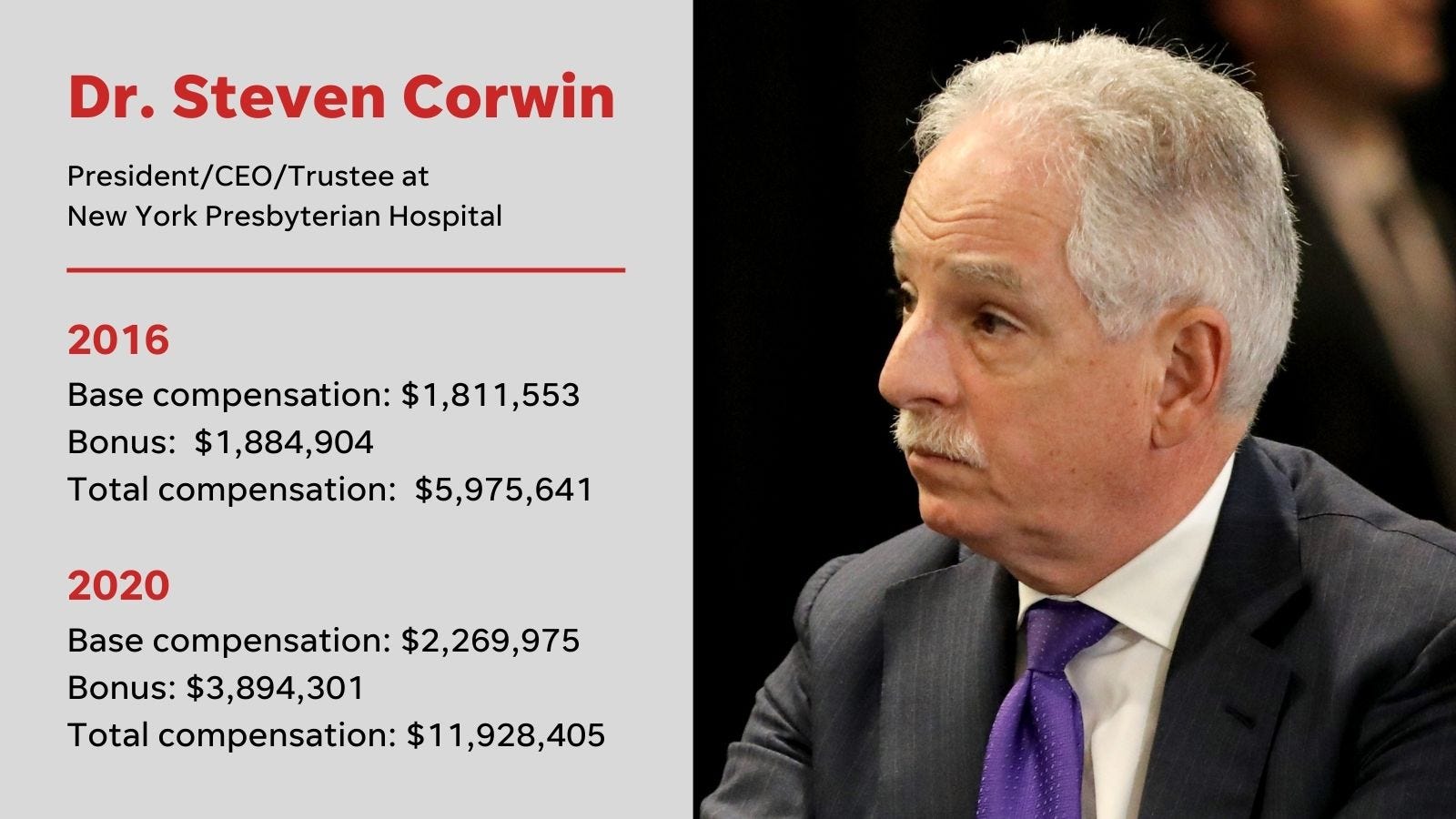

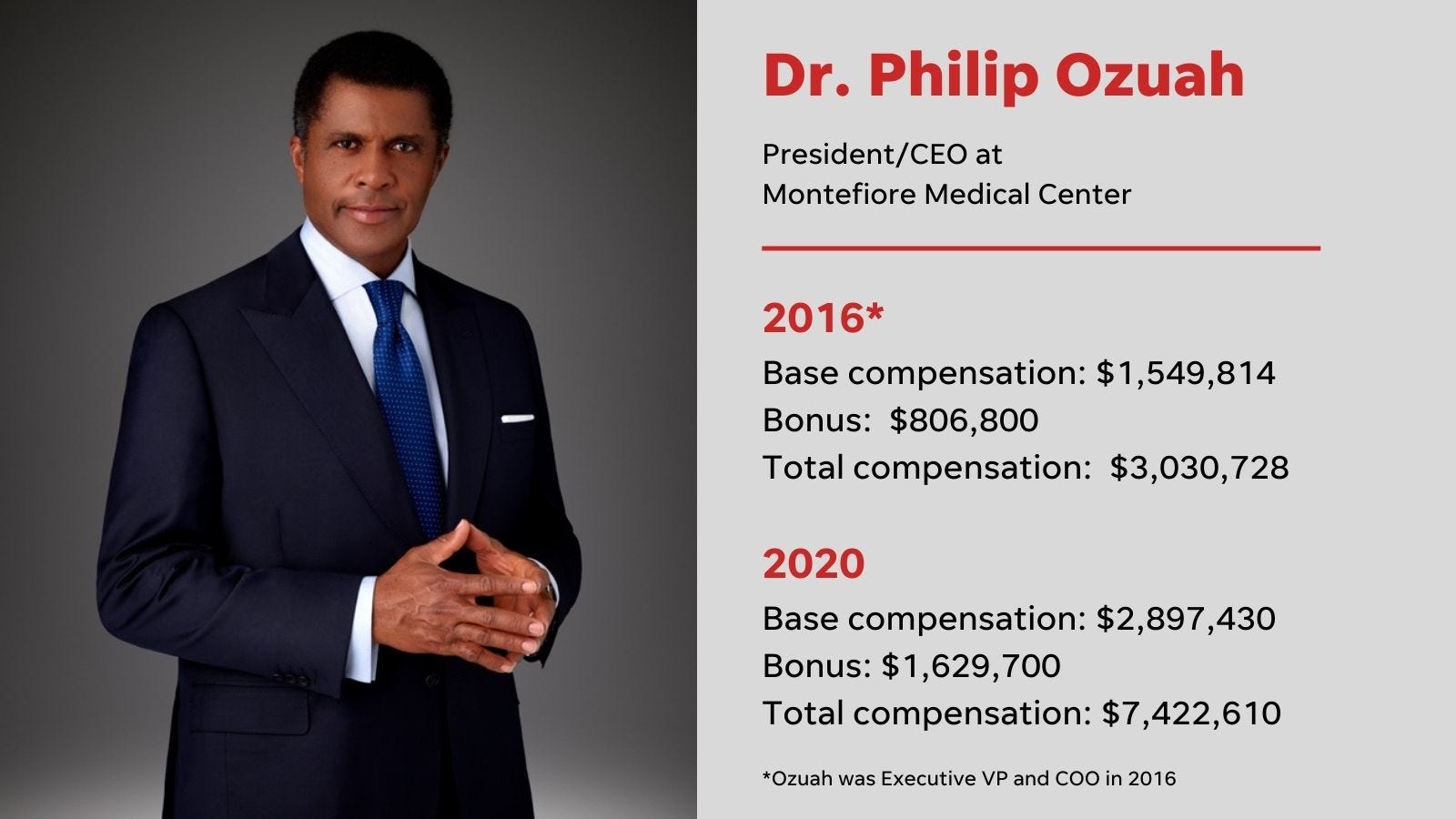

Just 10 executives took home bonuses of $1 million-plus, including leaders of some the state’s largest health systems, such as NewYork-Presbyterian, Northwell, Montefiore, Rochester Regional Health and Nuvance Health. The highest bonuses for an executive were just under $4 million.

But comparing the 2020 payouts to prior years is difficult because some tax filings for hospitals and health systems had yet to be released as of early August, while regulators and health providers worked through pandemic-era record backlogs. Some of the filings also only covered part of 2020 due to fiscal practices at some hospitals.

Still, USA TODAY Network’s analysis of 2020 records for a diverse sampling of hospitals and health systems from across the state suggested the payouts were comparable to, if not exceeding, the amounts paid between 2016 and 2019.

In a statement, Bea Grause, president of the Healthcare Association of New York State, said executive pay is set by each hospital’s board of trustees based on a variety of factors, all focused on recruiting and retaining experienced leaders to manage the operation and performance of complex and dynamic not-for-profit institutions.

“Variance in compensation strategies from hospital to hospital is expected,” Grause added. “Where there is no variance, however, is that every hospital executive in New York puts their patients and healthcare workers first.”

Conway, the hospital trade group spokesman, also outlined executives’ duties as part of the compensation calculus.

“In addition to focusing on the core mission of patient care and patient safety, hospital CEOs must master numerous financial, regulatory, and public policy challenges, as well as manage large physical plant operations, highly educated and skilled staff, and cutting-edge technology and services,” he said.

‘It’s just not sustainable’

While executives are getting millions in bonuses, Suzanne Barnes is considering switching jobs after working 18 years as a nurse at St. Elizabeth Medical Center in Utica.

But she is reluctant to leave her job in part because of the added stress it would put on her already overworked colleagues.

And despite the up to $3,000 in hazard pay bonuses St. Elizabeth provided to nurses under a union contract deal in 2021, Barnes said her roughly $75,000 salary still falls short of justifying her own added workload due to colleagues being laid off or leaving jobs earlier in the pandemic.

“I’m hoping and praying that the situation with staffing changes, but it’s just not sustainable to work like we’re working now,” Barnes said.

“I’m trying to hang in there because if I leave, that’s one more person my co-nurses don’t have to work with,” she added.

George Tharakan, a 35-year-old biomedical engineer servicing medical equipment at Vassar Brothers and other Nuvance hospitals in New York, also addressed the growing divide between frontline workers' wages and workload.

To bring home pay of about $85,000 per year, Tharakan said he often logs 70 to 80 hours per week, including overtime and on-call shifts.

The long hours in part stemmed from some of his colleagues leaving for better-paying jobs elsewhere, which prompted Tharakan to join the 1199 SEIU Healthcare Workers union during the pandemic. He noted the initial contract negotiations with Nuvance have stretched nearly two years as working conditions worsened.

“It has certainly been tough,” he said. “Ours is a department that, no matter what department reaches out for help, we get the call.”

Many frontline workers are voicing similar complaints at many hospitals across the state, according to their statements during a series of recent health care workers’ union picketing events and public advertising campaigns.

Lianne Lotaj, a 45-year-old nurse at Vassar Brothers, asserted the sheer scale of the pandemic workload warranted some form of hazard pay from employers and the government for all frontline medical workers.

Despite spending 17 years working in critical care, Lotaj described being overwhelmed as her 20-bed intensive care unit stretched to more than 80 beds during pandemic peaks. She also recalled desperately trying to shield her husband and daughter from the traumatic experience.

“Sometimes I wouldn’t even leave the parking lot, and I would sit there in my car and cry,” Lotaj said, adding she persevered so far, in part, thanks to the camaraderie among nurses.

“I always felt at peace with myself that I wanted to do the right thing to help the patient,” she said, “And you have to move on and keep going in this job.”