This part issue investigates how specific individuals and particular contexts shape masquerades in different parts of West Africa at different moments in time. This approach to the study of the art shifts attention away from understanding each instance of masquerade in terms of its relation to a particular cultural or ethnic group, a framework that lingers in analyses of the arts of Africa despite long-standing critique of it. Indeed, a masquerade in any place reflects the people and circumstances involved in its making and reception. Focusing on these aspects of masquerades uncovers fresh questions about agency, invention and audience for investigations of the art in any location.

A 1978 photograph from Ilaro in southern Nigeria shows a performer with a wooden headpiece balanced on the top of his head (Drewal and Drewal Reference Drewal and Drewal1983: 266, plate 168) (Figure 1). The headpiece images a human face with bright white, open eyes and an elaborate snake-laced coiffure. Behind the thin veil hanging below the headpiece, the masquerader's own face is clearly visible. His eyes gaze directly at the camera and thus at the photographer operating it. Art historian Henry John Drewal and performance theorist Margaret Thompson Drewal published the image and other photographs of masqueraders’ discernible faces in their generative monograph on Gelede performances in communities of southern Nigeria identified as Yoruba. Most Gelede performers they witnessed peered through a cloth or veil rather than eyeholes in a wooden mask covering the head (Drewal and Drewal Reference Drewal and Drewal1983: 265). Their photographs and assessments of masqueraders’ attire suggest that, at least in the late 1970s, Gelede audiences often saw and thus could recognize individual performers’ faces.

Figure 1 Unidentified Gelede masquerader. Photograph by Henry John Drewal, Ilaro, Nigeria, 1978. EEPA 1992-028-1130. Henry John Drewal and Margaret Thompson Drewal Collection, Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Yet when Drewal and Drewal published their book in 1983, studies of masquerade and other arts of Africa typically focused on groups rather than on the individuals so clearly integral to any event. Scholars framed analyses in terms of singular cultural or ethnic groups, and they sought to identify the foundational traits of each group. They implied that each group was rooted in a mythic past and people in the group shared a common language, religion, social organization and art. For scholars who before and after 1983 assessed masquerade and other arts as expressions of bounded cultural or ethnic group identities, people considered part of a particular group operated within established parameters consistent with the group identity (see, for example, Griaule Reference Griaule1938; Sieber Reference Sieber1962; Segy Reference Segy1976; Vogel Reference Vogel1977; Phillips Reference Phillips1978; Cole Reference Cole and Cole1985; Jedrej Reference Jedrej1986; Lamp Reference Lamp1996; Haxaire Reference Haxaire2009; Bouttiaux Reference Bouttiaux2009a).

Granted, Drewal and Drewal conclude their 1983 book with a chapter entitled ‘Gelede and the individual’. They argue that ‘a complete and realistic picture … illustrates the dynamics of Yoruba religion and the relationships between art and the individual, between cultural norms and individuality, and between history and diversity’ (Drewal and Drewal Reference Drewal and Drewal1983: 247; cf. Drewal Reference Drewal1989). Placed at the end of their book, the chapter's attention to individuality suggests that it provides a follow-up discussion to their more all-encompassing description of Gelede as a Yoruba phenomenon. This part issue reconfigures the relationship of individuals to the study of masquerade and places individuals at the front of analysis.

No masquerade performers are timeless reproducers of some fixed norm, and observers’ experiences of the art in all its heterogeneity have often contradicted their own communally bound interpretive frameworks. Attempting to characterize art identified with a single cultural or ethnic group in his essay ‘A Mumuye mask’ (Reference Rubin and Cole1985: 98–9), Arnold Rubin notes that ‘Mumuye’ refers to ‘a heterogenous group of people’. Masks identified with the group, he writes, ‘serve many and varied purposes’, and yet he still strives to present an encompassing definition of Mumuye masquerades. He signals the importance of group identity over individual identity, explaining that the events ‘focus the collective identities of age sets’ and ‘foster male solidarity and unity’ (ibid.: 98). A general description of a single type of performance that he indicates was common to different Mumuye communities closes Rubin's essay, implying a certain coherence among disparate communities.

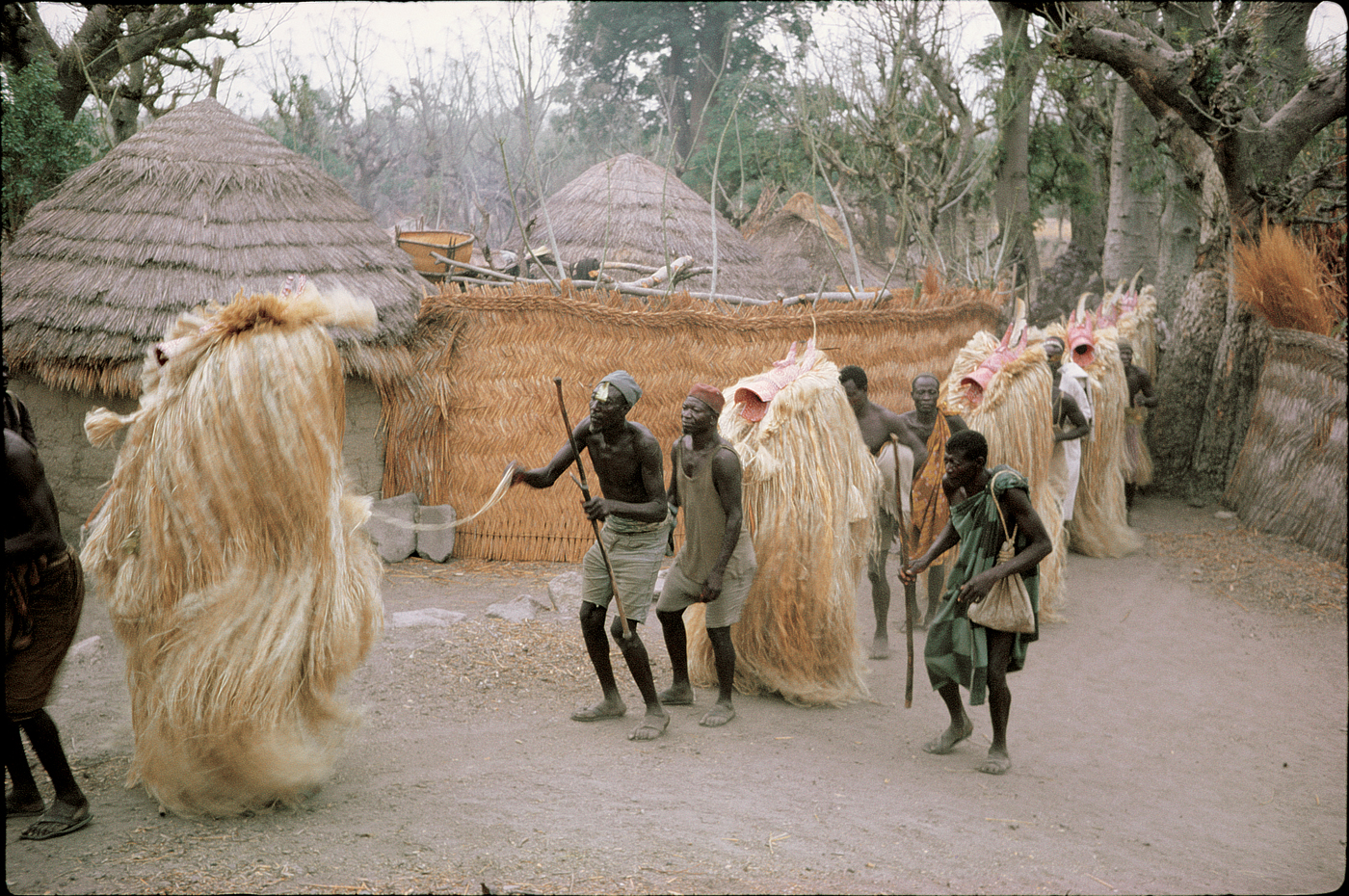

Notes and film footage in Rubin's archive indicate that the type of performance he presents as characteristic of Mumuye masquerade reflects his experience of a single event in April 1970 in just one town, Pantisawa. He observed another performance with different masks and a different sequence in the same month in another town, Zinna (also known as Zing) (Figures 2 and 3). Rubin's notes offer little information about the exact individuals involved with each masquerade or the specific circumstances surrounding it. However, local individuals and contexts, as well as his own presence at the events, likely contributed to the shaping of the two April 1970 performances the scholar witnessed. Rubin's photographs from Pantisawa further point at the individuality of the performers as the masks they wore reveal rather than conceal their torsos and legs. Nevertheless, in an effort consistent with studies of Africa at the time, Rubin emphasized the Mumuye-ness of the events rather than the identities of particular individuals or the exact circumstances involved in the staging or documentation of each event (see also Gagliardi Reference Gagliardi, Berns, Fardon and Kasfir2011).

Figure 2 Unidentified Vaa-Bong masqueraders performing in a funerary ceremony. Photograph by Arnold Rubin, Pantisawa, Nigeria, April 1970. Rubin Archive, Fowler Museum at UCLA, Neg. No. 2699. Image © Fowler Museum at UCLA.

Figure 3 Unidentified performers and men interacting with each other during a Vaa-Bong masquerade. Photograph by Arnold Rubin, Zinna, Nigeria, April 1970. Rubin Archive, Fowler Museum at UCLA, Slide No. A1.10.19.1. Image © Fowler Museum at UCLA.

As the twentieth century drew to a close, the idea of bounded cultural or ethnic groups with origins in timeless pasts attracted greater scholarly scrutiny. Arjun Appadurai (Reference Appadurai1988) argued that the framing of singular cultural or ethnic entities limits rather than facilitates study. Appadurai's comments resonate with observations that scholars of arts and performances of Africa have made since at least the 1940s. Based on his fieldwork in the late 1930s in northern Ivorian communities identified as Dan, Belgian art historian Pieter Jan Vandenhoute questioned the idea that the distribution of form maps neatly onto the distribution of cultural or ethnic groups (Petridis Reference Petridis2012; see also Vandenhoute Reference Vandenhoute1948). In the 1960s, American art historians Roy Sieber and Arnold Rubin contested the ‘hermetically sealed approach’ to the study of African arts and implored their colleagues to consider the impact of contacts, exchanges, interactions and migrations on artistic production (Sieber and Rubin Reference Sieber and Rubin1968: 12). Another two decades later, Sidney Littlefield Kasfir (Reference Kasfir1984) analysed the weaknesses in what she referred to as the ‘one tribe-one style’ model and advocated for alternative approaches to the study of African arts. There is no shortage of Africanist art historians who have raised similar concerns and have investigated the overlap and fluidity of certain cultural or ethnic attributions (for example, Bravmann Reference Bravmann1973; Vogel Reference Vogel1984; McNaughton Reference McNaughton1987; Berns et al. Reference Berns, Fardon and Kasfir2011; Petridis Reference Petridis2012; Gagliardi Reference Gagliardi2015).

Despite decades of scholarly critique, limiting frameworks for describing masquerades and other phenomena in Africa persist. With Sieber, Rubin questioned the approach in 1968, but then he reproduced it in his Reference Rubin and Cole1985 essay on Mumuye masquerade. Indeed, advances in theoretical assessments of old frameworks outpace changes in actual descriptions, meaning that tired paradigms endure. We need to change our vocabularies and language in order to transform our thinking and writing so that they align with theoretical advances. I have argued elsewhere that identifying art with a cultural or ethnic group often reveals little, if anything, about individual artists who created the works and specific contexts for the works’ creation or use. Rather, the terms designate a style of art largely defined by European and American art enthusiasts (Gagliardi Reference Gagliardi2015). Imagine knowing works by Paul Cézanne or Édouard Manet only as French rather than attributing the works to any individual artist or historical moment, thereby emphasizing the sameness of French art at all times rather than differences between individual works, their authors and their contexts of production. Or consider our attention to the specificity of performances in international centres. A production of The Lion King in New York is not the same as a production of The Lion King in Shanghai (Kaiman Reference Kaiman2016; Qin Reference Qin2016). Even in the same place, a production of Hamilton one night is not exactly the same as a production of Hamilton another night. The musical's cast changed their performance for the June 2016 Tony Awards in response to a mass shooting that took place hours earlier in a nightclub a thousand miles away (Reilly Reference Reilly2016; Spanos Reference Spanos2016). And the cast addressed a specific audience member – American Vice President-elect Mike Pence – at the end a November 2016 performance (Mele and Healy Reference Mele and Healy2016). Masquerades and other events in other communities also vary in response to specific individuals and specific contexts.

To unbind our thinking about masquerades and other arts produced across the vast African continent and often framed as ‘traditional’, ‘classical’ or ‘historical’, we likewise need to attend to the specificity of those arts’ making, viewing and circulation. We must recognize what Margaret Thompson Drewal (Reference Drewal1989: xv) characterizes as the ‘instrumentality of performers’ and shift our analysis to what Bruno Latour (Reference Latour2005: 28) describes as the ‘on-going process made up of uncertain, fragile, controversial, and ever-shifting ties’ among individuals operating within particular contexts. Such a process-centred analytic that focuses on specific individuals within specific contexts will illuminate past and present dynamism. And as Kai Kresse and Trevor Marchand (Reference Kresse and Marchand2009: 3) explain, context ‘is not merely location’ but also encompasses material objects, built environments, interpersonal networks and specific events. It is in such contexts marked by the shifting webs of relations and events in local, regional and global spheres that masquerades transpire. No masquerade, therefore, can be understood to typify a single cultural or ethnic group as such. Writing about Yoruba performances, Drewal (Reference Drewal1989: 29; Reference Drewal1992: 23) asserts that ‘it would be naïve and reductionistic to think of [an event] as a preformulated enactment or reenactment of some authoritative past – or even as a reproduction of society's norms and conventions’. Her observations extend beyond communities identified as Yoruba. Masquerades and other performances are always contingent and always driven by the distinct performers and audience members involved, for no individual is a pure distillation of a culture, or even of a particular moment.

Distinct individuals and audiences

In a popular text on African masquerades, Ladislas Segy (Reference Segy1976: 12) claims that ‘the masked dance was rooted in a communal need, and as the participants shared in the experience, the mask became a powerful implement for achieving a homogeneous mass consciousness’. He continues: ‘The dissolution of the individual into collective consciousness is the key to the African's way of life.’ Segy's emphasis on ‘communal need’ and ‘mass consciousness’ leaves little if any room for individuals’ varied reactions to masquerade performances. He also suggests that masquerades contribute to ‘the African's feeling of being part of the natural order of things and each generation's repetition of the same cultic actions rooted in the sacred past’ (ibid.: 8). Segy's interpretations of particular masks’ meanings have been characterized as ‘flights of pure imagination’ (Vogel Reference Vogel1977: 11). But his focus on collective identity and response reverberates with some twentieth-century writers’ approaches to masquerades in Africa. Such entrenched notions deny any recognition of the distinct individuals and contexts that have given rise to and shaped diverse instances of the phenomenon.

Observers of masquerades in very disparate times and places report that specific people have at specific moments in time invested in the art in order to respond to, comment on, or have an impact on certain people or events. For example, Z. S. Strother (Reference Strother1998: 229–63) examines how different generations of people in Pende-speaking communities of present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo used masquerade to comment on the oppressive colonial state and its abuses of power. Claudie Haxaire (Reference Haxaire2009: 551–9) describes how certain Guro-speaking communities of present-day Côte d'Ivoire developed and updated masquerades in response to specific concerns about sexual behaviour, economic crisis, or other events. And John Thabiti Willis (Reference Willis2014) demonstrates how, in the late-nineteenth century, a woman identified as Moniyepe brought an Egungun masquerade known as Oya to Ota, a town in present-day Nigeria. Moniyepe's senior co-wife, Oshungbayi, sponsored the first performance of Oya. By tracing the inheritance and transfer of, and investment in, a specific Egungun masquerade in a specific place and at a specific moment in time, Willis examines the complexities of the practice. His focused analysis makes clear that masquerade reflects more than the repetition of actions rooted in the past (see also Willis Reference Willis2017). Rather, it reflects personalities and negotiations particular to time and place.

Masquerades also depend on audience engagement and interaction. As Elizabeth Tonkin states: ‘Every Mask [masked performer] is part of an event, which can only be intelligible when understood as a performance with complex interactions between Masks and non-maskers’ (Reference Tonkin1979: 243; see also Cole Reference Cole and Cole1985: 22). Few studies of African masquerades probe audiences’ impact on masks and masquerade.Footnote 1 According to Strother (Reference Strother1998: 268), this lack of critical attention to the role of audiences in masquerade stems from modernist studies’ emphasis on authorship. Yet audiences respond to and evaluate performances, and their interpretations of certain masks may at times reframe or even invert intended meanings (ibid.: 267–81). Prompted by a childhood response to masquerade as a member of its audience, Michael Taussig (Reference Taussig1999) considers differences between just and unjust revelations in his meta-analysis of the art. According to Taussig, masks constitute a form of public secrecy, or ‘knowing what not to know’, and the ‘just revelation’ or ‘unmasking’ maintains rather than destroys the secret (ibid.: 2). Taussig's framing of masquerade as the public secret implies a shift in attention to audiences, the people who must know what not to know.

Observers of masquerades in Africa have at times referred to the reactions of audiences in this world and the otherworld even if they have not focused their analyses on how various human audiences impact on specific events. Masquerade observers have referred to certain instances when audience members appeared to know who was behind a mask. And they have reported masqueraders’ and audience members’ mutual recognition of each other. For example, Karin Barber (Reference Barber1981: 739) explains that an elderly woman in the town of Òkukù, Nigeria, sang praises for a masked character and the man who wore the mask after the woman encountered the man only partially dressed in the mask. Punishment, including a large fine, and other negotiations followed before the woman returned to the town. Barber notes that another woman suggested women know men wear masks.

Polly Richards refers to men, women and children in Dogon communities of Mali who acknowledged that men in particular wear dance masks. She recalls overhearing a group of young boys who discussed such observations (Richards Reference Richards2006: 101). A nearby elder intervened and asked the boys if masks speak, perhaps in an effort to cast doubt on the boys’ discovery or to suggest that the boys still did not fully understand masking (ibid.: 101). Richards also reported hearing women discuss the relative attractiveness of men based on men's abilities to dance masks.Footnote 2 In at least some places, audience members evidently recognize individual performers but may avoid public announcement of performers’ names (see also Drewal Reference Drewal1989: 192–5).

A masquerader may engage differently with different audience members depending on the latter's specific identity. Richards (Reference Richards2006: 102) explains that a woman told her that a masquerader may pose a greater threat to a woman when the woman and performer know each other. Strother similarly explains that, in performances she observed, masqueraders evaluated the identities of people in the audience before acting. She reports protocols that required masqueraders to differentiate between people they were permitted to chase and hit with their whips – including young boys, teenage girls and their mothers – and people considered off limits, including mask makers, middle-aged women other than their mothers, and strangers. Strother also notes that audience members evaluated the size, style of movement, hands and feet of masqueraders in order to assess who the performers were (Strother Reference Strother2008: 8–13).

Marcel Griaule characterized the mask as a persona, such that ‘[the mask], and not the wearer, provokes exaltation and admiration’ (Griaule Reference Griaule1938, cited in Bouttiaux Reference Bouttiaux2009a: 11). Yet deft mask wearers may focus on their audiences, recognize prominent individuals within crowds, and look for ways to capture audience members’ attention. Western Burkinabe hunters’ associations began investing in masks and masquerade performances at the end of the twentieth century in order to build public support for their campaigns to combat thievery and other crimes (Gagliardi Reference Gagliardi2013) (Figure 4). During an April 2007 event I attended, masqueraders stopped at the prefect's house to greet the government official. They also greeted other political leaders in the town and stopped at important places, including sites where some of the town's most renowned specialists maintained power objects. One of the masqueraders I later interviewed recognized his own agency when he wears a mask. He explained that, when he performs, he looks for ways to animate the event and make audiences laugh. He offered an example framed in the context of our interview, which he noted lacked the liveliness of a performance. Spying my water bottle, he explained that if he were dressed as bala (porcupine), he would have grabbed the bottle and run with the aim of making the audience cheer. He added that a dynamic performance leaves the performer hot and tired at the end.Footnote 3 Successful execution of the bala masquerade demands a performer's constant alertness to his surroundings, including the audience, and sensitivity to timing. Examples abound of other western Burkinabe hunters’ masqueraders interacting with audiences to make people laugh. A performer in one town begged for money from a woman to buy bread from a bicycle pedlar, played with a child, and posed for my camera as he sat on the ground during a February 2007 event commissioned by a national politician to honour foreign donors.Footnote 4 Another performer stopped to inspect a vendor's stand, eliciting laughter and applause from the young men seated for a May 2007 event to honour a deceased master hunter.

Figure 4 Detail of a photograph of performers greeting the audience during a hunters’ association masquerade. Photograph by Constantine Petridis, Noumoussoba, Burkina Faso, 4 January 2014.

Masqueraders have long recognized and addressed specific audience members, including foreigners. For example, French colonial administrator Maurice Delafosse (Reference Delafosse1909: 1–2) wrote about night-time performances he attended in the early twentieth century during the great funerary ceremonies for the father of Gbon Coulibaly, the distinguished local leader of Korhogo, Côte d'Ivoire. According to Delafosse, the governor of the colony, also in attendance, informed Coulibaly's representative that he, the governor, needed to leave the performance before it ended. The representative relayed the message to one of the masqueraders, referring to the governor as the ‘Big Boss’. The masquerader asked, ‘The Big Boss?’, and pretended to look everywhere for someone who fitted the description, even though the governor sat just a few steps away. The governor stood and gave 20 francs to the performer and the rest of the masquerade troupe. The performer pointed to the governor and responded, ‘Ah! I see, the Big Boss, here, here!’ The crowd burst into laughter. Delafosse's account demonstrates performer–audience interaction. It also suggests that the foreigner's presence contributed to rather than detracted from the event.

At times, masquerades also emphasize the individuality and humanity of performers. In the first penetrating book-length study of a single performer of African masquerade, Patrick McNaughton (Reference McNaughton2008) reflects on the 1978 performance of Sidi Ballo in a small Malian town. McNaughton demonstrates the centrality of Ballo's personality and agency to the successful event. Anne-Marie Bouttiaux (Reference Bouttiaux2009b) likewise recognizes the importance of distinguishing among individual performers in her analysis of masquerades in Côte d'Ivoire in the late 1990s. Bouttiaux explains that dancers often competed with each other in pursuit of distinction and fame. She also reports that masqueraders at times lifted up headpieces covering their faces, revealing their identities to onlookers (ibid.: 64, 66).

Shifting focus

Despite references to specific individuals or performances in some accounts, many recent studies of African masquerades have continued to overlook how masquerades may have always been subject to variation or change. They have also sidestepped the role of specific individuals and particular contexts in the making and reception of the art. More than fifteen years ago, theorist Achille Mbembe (Reference Mbembe2001: 3) observed:

it must not be forgotten that, almost universally, the simplistic and narrow prejudice persists that African social formations belong to a specific category, that of simple societies or of traditional societies. That such a prejudice has been emptied of all substance by recent criticism seems to make absolutely no difference; the corpse obstinately persists in getting up again every time it is buried and, year in year out, everyday language and much ostensibly scholarly writing remain largely in thrall to this presupposition.

With respect to writing about masquerade and other so-called historical or classical arts of Africa, Mbembe's observations still resonate. Characterizations of Africa that Mbembe critiques assume ‘things and institutions have always been there [so] there is no need to seek any other ground for them than the fact of their being there’ (Reference Mbembe2001: 3–4, emphasis in the original). Such characterizations emphasize ‘the importance of repetition and cycles’ rather than ever-fluctuating interactions and circumstances (ibid.: 4). And they deny recognition of ‘the “individual”’, instead presupposing that people within a particular system are ‘captives’ of that system (ibid.: 4).

What is needed in order to break free of the cultural or ethnic pigeonholing that has dominated studies of masquerades and other arts is an exploration of specific individuals and particular contexts in the making of and responses to those arts. Focusing on a person, genre or audience can open a window onto how different individuals and circumstances variously shape the creation, execution or reception of performances that involve different coverings of the human body. Such an approach to the study of masquerade can also shift attention to different dimensions of agency, be it a masquerader who causes audiences to roar with laughter, an unseeing audience that experiences performances from within dark rooms, an artist who creates headpieces imaging named individuals, or the agency of human and otherworld entities integral to masquerade design.

Each author of the articles in this part issue draws on months of fieldwork to offer different perspectives on the ways in which specific individuals shape masquerades. The authors account for their presence at particular events and their interviews with people with different experiences of masquerade. Their attention to their role in the construction of knowledge reflects an understanding that the status of objective researcher is impossible to maintain (Favret-Saada Reference Favret-Saada1980 [1977]: 16–24; Kresse and Marchand Reference Kresse and Marchand2009: 7–8). The authors similarly recognize the different positions of the people they interviewed. Not every person in a particular place may have equal knowledge of that place, its history or its arts, and people with knowledge may set different limits on the information they are willing to share (see also Strother Reference Strother2000: 69–70).

In addition, the authors demonstrate attention to the framing of their questions and other nuances of information gathering. This point is important because the questions observers ask shape the responses people offer in return, and observers who in the past have approached masquerades as expressions of particular cultural or ethnic group identities may have unwittingly embedded the assumption into their questions or their analyses of the answers they received. But answering questions about general events or cultural characteristics rather than about any specific event or dynamic may prove difficult for many respondents. When people I met in western Burkina Faso asked me about my own experiences and the place I called home, they helped me identify difficulties in responding to certain kinds of questions: namely, questions designed to elicit general statements rather than reflections on particular experiences. For example, during an October 2006 visit to a courtyard that I had visited many times before to interview Karfa Coulibaly, Coulibaly's teenage sons started a series of questions about who pays for weddings and funerals in the distant place they considered my home. I found it difficult to provide a single answer that accurately described who had paid for all my friends’ weddings or all the funerals about which I had ever known. I could not even work out who I would include in my ‘all’. Did my interviewers want to know about all Americans, about just the people in Orange, Massachusetts, my home town, or about the people in Los Angeles, California, where I had most recently lived in the US? Generalized answers about the events’ choreography proved even trickier for me to provide. Each wedding and each funeral I thought about as I tried to answer their questions had differed as a result of the specific people involved and particular circumstances surrounding the event. I explained what a standard expectation might be and then said that I knew many instances when what actually happened deviated from that standard.

A similar disjuncture between standard expectations and actual happenings seems to apply to masquerade and other events. As I listened to what people in western Burkina Faso told me about their own experiences, I noticed that they also differentiated between abstract descriptions of how an event should normally proceed and accounts of what actually happened during any single event. The norm was rarely, if ever, achieved exactly. In fact, I found that my interviews were more productive when we discussed actual events rather than some hypothetical norm. And because I wanted to hear what people had to tell me about their experiences, rather than fit them within some predetermined frame, I tried to disencumber myself when interviewing from the ideas and information I had read prior to beginning my fieldwork. More specifically, I sought to distinguish between using earlier studies to formulate questions to open the field of inquiry, and using them to guide people into expected answers, thereby closing the field (see also van Beek Reference van Beek1991; Reference van Beek2004; Brett-Smith Reference Brett-Smith1994: 17; Amselle Reference Amselle1998: 35; Strother Reference Strother2001). The authors of the articles here draw on a range of methods to open their analysis of masquerade.

The specificity of masquerade

This part issue developed out of the session ‘Performing personalities in Africa’ that I organized for the 2014 Arts Council of the African Studies Association triennial symposium in Brooklyn, New York. It highlights how a process-centred analytic informs understandings of individual agency and singular contexts at the centre of masquerade performance and reception. Each author investigates how, within specific contexts, individuals have variously conceived, shaped and experienced different performances. Taken together, the articles expand possibilities for thinking about the art without insisting on any single frame for understanding all masquerade everywhere.

Samuel Mark Anderson draws on his fieldwork in Sierra Leone since 2010 to investigate humorous performances of Siloh Gongoli, the ‘coalescence’ of the performer Siloh and masquerade character Gongoli. Anderson focuses on Gongoli as Mende art, but he also observes that ‘Gongoli and similar masked figures proliferate in many neighbouring communities throughout Sierra Leone and Liberia, suggesting that [the character's] antics have national and regional relevance’. According to Anderson, when Gongoli drops his mask and reveals his human face, audiences roar with laughter over a comic element that would be absolutely unacceptable for more socially powerful masked dances. Spectators find Gongoli acts performed by the nomadic performer Siloh especially felicitous, since Siloh's own eccentric and bumbling personality matches that of the character he portrays. Anderson's understanding of Siloh as Gongoli stresses the singular relation of a particular performer to a masquerade persona within specific contexts, reinforcing the idea that an individual's skill and position within larger networks shape performance expectations and reception.

Fieldwork conducted in western Burkina Faso since 2004 informs my own analysis of unseeing audiences in West African power association masquerades. Organizations’ leaders bar most women, including me, from seeing the events. Yet women look forward to masquerades they are prohibited from seeing, and they gather in dark rooms to attend the events. They listen to performers and at times call out to engage with performers outside. They also offer different accounts of their experiences of the events. This attention to unseeing audiences reconfigures our understanding of women's contributions to power associations and what constitutes an audience for a live performance.

Lisa Homann examines the ways in which individuals have shaped masquerade practices in and around Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, since the mid-1990s. Based on fieldwork she has conducted in Burkina Faso since 2006, Homann focuses specifically on portrait masks carved by the late André Sanou, a Burkinabe sculptor who, in 1996, reportedly invented the form to honour deceased individuals. Sanou based his portrait masks on photographs of individuals taken when the people were alive. Homann reports that, when performers wear portrait masks, audiences remember specific individuals to whom the headpieces refer. Homann investigates the named artist's invention and controversy as these relate to the masks’ explicit visual references to specific people. She also demonstrates that, due to divergent local responses to the new form, the art does not spread evenly across a region. Homann's analysis provides a foundation for future historical study of masquerade in the region of Bobo-Dioulasso. It also draws attention to the possibility that discussion, debate and uneven distribution of new forms may have surrounded the emergence of new masks and performances in other times and places.

Drawing on his field-based study of Ivorian masquerades in Côte d'Ivoire in the 1990s and in the US since the early 2000s, Daniel Reed emphasizes the processual nature of performance and argues that it may best be understood ‘as being’. He considers how human identities and agency impact on performance design. He also investigates how otherworldly agency remains central to the events, including events for which advertisements announce names of individual masqueraders. According to Reed, performances reflect ambiguous borders between individual identities and otherworldly agency, and the borders shift depending on the specific performers and contexts for a particular event.

In his commentary on the four studies, Patrick McNaughton, who served as a discussant on the 2014 triennial panel, reflects on challenges of analysing masquerade and considers how this collection of articles relates to other studies of the art published at different moments in time. But rather than reveal the full contents of the other articles in the collection, McNaughton entices readers to take a look at them. He examines how each author assesses the complex roles of individuals in divergent masquerade practices. He also highlights other themes that may appeal to readers, including secrecy – which he recognizes as ‘a genuine form of collateral, a resource that can be manipulated as tangibly as the materials used in sculpting or the rules that guide social action’ – and networks, which he characterizes as ‘individuals linked together in collective action’.

As McNaughton observes, each author contributing to this collection offers different perspectives on the ways in which particular people create and understand masquerades. Grounded in data specific to particular times and places, the divergent analyses foreground the complexity of masking and show it as a dynamic rather than static art. In the wake of conflict in Sierra Leone, performances have thrived. Western Burkinabe women who described participating in certain masquerades they were prohibited from seeing prompt recognition that audiences consist of more than spectators who can see an event. An artist in Burkina Faso turned to photographs of people to invent a new genre that audiences embrace and contest. And masquerade practices travelled from rural towns in Côte d'Ivoire to small communities in the US by way of major metropolises.

Masquerades may change across time or space, they may respond to certain political circumstances, or they may shape or be shaped by their varied audiences. If, as Latour argues, the social does not exist outside the ever-changing webs of relationships that specific people in specific places build at specific moments in time, then we need to investigate those webs. This approach is especially important for analyses of masquerade and other arts of Africa that for too long have clung to cultural or ethnic group distinctions without accounting for the making of those markers.