Document prepared by Neil MacKinnon, Chair of the Council of Deans

The deans were asked by Provost Nelson to address two questions during their meeting on January 23, 2019. The two questions were as follows:

- What are our top financial pinch points in FY 20?

- What incentives do we want included in the new budget model?

Following this meeting, a summary of the main points from the discussion on these questions was prepared and circulated to the deans with additional discussion/input from the deans at the Deans’ Roundtable meeting on February 6, 2019.

1). What are our top financial pinch points in FY 20?

As the Council of Deans have previously articulated in writing in 2017, and in 2018, there are a number of financial pinch points in the current performance-based budget (PBB) model which create significant challenges for the colleges. These financial pinch points remain in place currently and have only intensified over time.

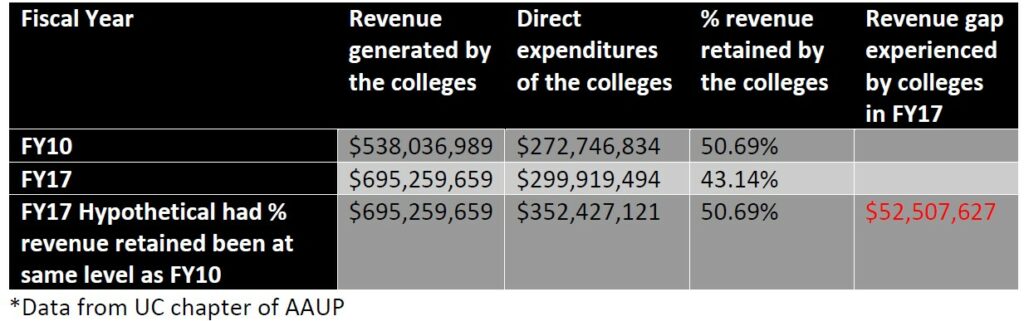

The major financial pinch point in FY2020 will come from the 4.1% change to the threshold, as it will add to the cumulative changes to the threshold, and faculty and staff salary increases, over the years. Yet another cut means that we will lose staff and/or teaching capacity because cuts of that size must come from these accounts. These choices weaken our infrastructure to support students and the primary educational mission of UC. While 4.1% may not seem like a large change, it is the cumulative effect of the changes over a period of 9+ years that has resulted in a significant change, as the UC chapter of AAUP articulated in their analysis of PBB in winter 2018. In FY10, the first year of PBB, the colleges kept 50.69% of their revenue. By FY2017, this had fallen to 43.14%. Had the colleges kept 50.69% of their revenue in FY2017 as they did in FY2010 at the start of PBB, this would have resulted in an additional $52,507,627 in revenue for the colleges collectively, as can be seen in the table below.

In no particular order, the additional financial pinch points include:

- The disconnect between the budgets of the colleges and actual expenses and the need for rebasing. While setting the baseline budgets for each college at the onset of PBB may have been based on a rational and well thought-out approach, in 2019 it is apparent that there is a large disconnect between the budget allocations the colleges receive centrally through PBB and their expenses. For example, there is a wide range among the colleges in the percentage of total college budget dollars which are covered by PBB. In some cases, the PBB allocation doesn’t even cover salary expenses, let alone operating expenses.

- Continued addition of costs which have trickled down to the colleges in recent years. Since the onset of PBB, there have been significant changes in the expenses born by the colleges, typically which are mandated by central administration. In spring 2018, the deans documented 31 such costs which have trickled down to the colleges. Since then, there have been additional costs, such as the dissolution of the central pool of instructional designers with no notice to, or input, from the colleges, passing along international student recruitment fees to the colleges, and reducing healthcare insurance coverage for graduate students. Similar the changes to the threshold over time, while some of these trickle down costs are not large, it is the cumulative effect which has been devastating to the college budgets.

- Lack of symmetry in revenue growth and decline. A basic premise of PBB since its inception is that colleges split any access PBB surplus 50/50 with the Provost’s office but must fully bear the revenue gap when enrollment falls. Not only does this fail the basic fairness eyeball test, it can significantly hamper colleges when enrollment drops over an extended period of time. It should be noted that often the reasons for an enrollment drop are beyond the control of a college or dean, such as a change in the labor workforce, or a third party distance learning vendor.

- Rolling Debt. While some colleges can get out of a financial hole with enrollment growth and cost efficiencies, a decade of experience with PBB has taught us that there will be cases when some colleges will be unable to fully get rid of debt, even with significant cuts and implementing efficiencies. It is time to consider forgiving the rolling debt for these colleges.

- Impact on non-revenue generating academic units. The years of continued reductions of permanent budget on non-revenue generating core academic units such as UC Libraries harms UC’s ability to support student success, faculty research productivity, growth and innovation.

2.) What incentives do we want included in the new budget model?

As with the previous question, the Council of Deans have previously articulated in writing in 2017, and in 2018, our recommended changes to PBB. We recognize there is a balance between transparency and fairness and having a model that takes into account the differences between the colleges while not making the model overly complex or burdensome.

Our overall recommendation is to ensure that the incentives are tailored for each college. We need to be intentional about our differences and create different incentives.

The incentives that the Council of Deans would like to see in a revised financial model at UC moving forward are as follows, in no particular order:

- Create incentives for growth, but in a meaningful way, given that the capacity for growth differs greatly across and within colleges.

- Include student retention as one of the incentives, but careful thought will need to be given to its implementation. For example, since student retention is already very high in some colleges and there is little room for improvement, how would an incentive for student retention work in those cases?

- Include research dollars as an incentive for the research colleges, but care must be shown to ensure that this aligns with the new budget model, as there is a disconnect between PBB and incentivizing research currently.

- Gains in program/college rankings.

- Improvement in diversity of the student body, faculty and staff.

- Improvement in number of students transitioning to the Clifton Campus (for the regionals).

- Enhancing student access (students who are weaker academically typically take more resources).

- Enhancing the quality of students in programs. This is seemingly counter to the previous incentive (#8) but may be important for some programs to increase in rankings.

- Improvement in the number of applicants. For example, the applicant pool is rate-limiting for graduate programs.

- Establishment of collaborative programs that cut across colleges.

- Closing programs that are no longer needed because of changes in the workforce or because of ongoing financial loss. Ideally, there would be a central pool of resources needed for buy out/ early retirement for the faculty associated with the programs designated for closure.

- Taking risks; not punishing colleges if some of those risks do not succeed. To have alignment with the innovation agenda that is part of Next Lives Here, there should be incentives in place for colleges to create new programs, beyond just the promise of new revenue years down the road.

- Improvements in degree completion rates.

- Creating a sustainable new budget solution to ensure non-revenue core academic units’ ability not only just to survive, but also to thrive along with college and university’s growth.

- Measures of student success in outcomes such as state/national licensure test scores and certificate completion success